The Onerous Burdens of Sex Offender Registration Are Not Punishment, the 10th Circuit Rules. They Just Feel That Way.

According to the appeals court, the relevant question is what legislators were trying to accomplish.

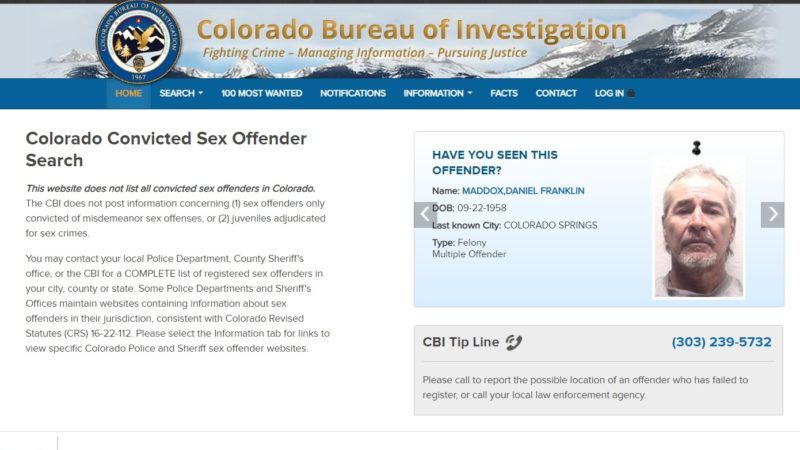

Online sex offender registries, which all 50 states maintain as a condition of federal funding, stigmatize the people listed in them long after they have completed their sentences, creating obstacles to housing and employment while exposing registrants to public humiliation, ostracism, threats, and violence. Three years ago, a federal judge ruled that such consequences amounted to cruel and unusual punishment of three men who challenged their treatment under Colorado's Sex Offender Registration Act. Last week a federal appeals court overturned that decision, saying the burdens imposed by registration do not even qualify as punishment, making the Eighth Amendment irrelevant.

While that conclusion might seem counterintuitive, it comports with the U.S. Supreme Court's understanding of sex offender registration, which it views as civil rather than punitive. Even though there is no evidence that publishing information about people convicted of sex offenses protects public safety, that is what legislators claim they are trying to do. And since their goal is prevention rather than retribution, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit ruled, any harm inflicted by this policy is incidental.

That is not how it looks from the registrant's perspective. In Colorado, anyone convicted of a listed offense must register with local police either annually or quarterly for the rest of his life, although some sex offenders can eventually petition for relief from that requirement. The names, offenses, photographs, addresses, and birth dates of people with felony convictions are readily available online to the general public, which means their records follow them wherever they go, no matter when they committed their crimes or how long they stay out of trouble.

The lead plaintiff in this case, David Millard, pleaded guilty to second-degree sexual assault on a minor in 1999. He served 90 days in jail and eight years of probation, but that was not the end of his punishment.

Millard was forced to move repeatedly after his status as a registered sex offender was revealed, once by police and once by a local TV station. The second time, he had to fill out about 200 rental applications before finding an apartment he could rent. He nearly lost his job at a grocery store after a customer saw his name and photo on a sex offender website.

Millard later bought a house in Denver, which is periodically visited by police officers seeking to verify his address. "If he is not home when they visit," U.S. District Judge Richard Matsch noted in the 2017 decision that the 10th Circuit overturned, "they leave prominent, brightly colored 'registered sex offender' tags on his front door notifying him that he must contact the DPD."

As you might imagine, this public shaming makes things more than a little awkward with the neighbors. Millard has been a target of verbal abuse and vandalism, and he worries that worse may be coming. "Because of the fear and anxiety about his safety in public," Matsch wrote, "Mr. Millard does little more than go to work, isolating himself at his home."

Another plaintiff, Eugene Knight, was convicted of attempted sexual assault on a child in 2006 based on a crime he committed when he was 18. Like Millard, he served 90 days in jail and eight years of probation. Now a "full-time father" because he has been unable to find work that pays well enough to cover the cost of child care, Knight is not allowed on school grounds to drop off his kids or attend school events.

The third plaintiff, Arturo Vega, pleaded guilty to third-degree sexual assault, a crime he committed when he was 13. Although juvenile offenders generally are not included in Colorado's public database, Vega is listed there because he failed to comply with registration requirements he did not understand. He has tried twice to get off the registry. Both times his petitions were rejected by magistrates who insisted he prove a negative: that he was not likely to commit another sexual offense.

While acknowledging the price these men continue to pay years after completing their official sentences, the 10th Circuit said the relevant question is what Colorado legislators were trying to accomplish: "The statutory text itself explains that 'it [was] not the general assembly's intent that the information [contained in the Registry] be used to inflict retribution or additional punishment on any person,' but rather [the law] was intended to address 'the public's need to adequately protect themselves and their children' from those with prior sexual convictions." Even looking beyond that avowed intent, the appeals court added, registration does not have the hallmarks of a criminal penalty recognized by the Supreme Court.

Does registration "resemble traditional forms of punishment"? Matsch likened it to public shaming, banishment, and parole. The 10th Circuit rejected those analogies.

Does registration "impose an affirmative disability or restraint"? The 10th Circuit concluded that the policy's impact on the plaintiffs' "abilities to live, work, accompany their children to school, and otherwise freely live their lives" did not meet that test.

Does registration "promote the traditional aims of punishment"? Matsch noted that Colorado's registration requirements are based purely on the statutory classification of the offender's crime, rather than an individualized assessment of the danger he poses, which to his mind suggested retribution was one aim of the law. The 10th Circuit rejected that inference. Matsch also noted testimony in which the director of the state agency that maintains the sex offender database cited deterrence as one goal of registration. "Deterrent purpose alone is not enough to render a regulatory scheme criminal in nature," the 10th Circuit said.

Does registration have "a rational connection to a nonpunitive purpose"? Matsch conceded that point, and the appeals court thought it was enough to note that Colorado's law "requires more serious offenders to register more often than others," which gives you a sense of what rational means in this context.

Is registration "excessive with respect to [its] purpose"? Matsch thought the law's "very long registration requirements and substantial disclosure of personal information, without any individual risk assessment or opportunity to soften [its] requirements based on evidence of rehabilitation, were excessive in relation to [the law's] supposed public safety objective." The 10th Circuit said that conclusion was inconsistent with its precedents.

Other courts have been more receptive to the argument that registration is punishment by another name. In 2016, for example, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit concluded that Michigan's sex offender registration scheme was punitive, meaning its requirements cannot be imposed retroactively. The supreme courts of several states, including Alaska, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania, have reached similar conclusions.

But in the 10th Circuit, registration does not count as punishment, notwithstanding its onerous costs and dubious benefits. In practice, that analysis hinges on what legislators say they want to do, not what their law actually accomplishes.

Show Comments (25)