The Earl Weaver Case for Rand Paul's Libertarianism

Instead of dwelling on how the candidate falls short on foreign policy, it's worth imagining what a President Paul might do

Since even before his primary victory against GOP establishment senatorial pick Trey Grayson in Kentucky, Rand Paul, arguably the most libertarian senator since Barry Goldwater, has been subject to a perhaps-surprising level of criticism from libertarians, particularly when it comes to foreign policy.

In a May 2010 Reason profile of Paul, W. James Antle, III, found some fans of Paul's father who were already worried about the son:

"Rand is terrified of the foreign policy his father has supported," opines a libertarian activist who says he was rebuffed when he tried to arrange a meeting between Rand Paul staffers and J Street, an organization that bills itself as a more dovish Israel lobby. […]

"All of the signs I've seen so far are bad," the activist says. "And politicians usually get worse rather than better once they're in office. But we're still trying to be hopeful." Another professional libertarian declares that the candidate will "either be exactly the kind of thing we need, someone who is reliable on the most important things but willing to be tactical when he needs to be, or he'll turn out to be so pragmatic that he's indistinguishable from other Republicans."

More recently, in Tuesday's New York Times, Reason Senior Editor Brian Doherty criticized Paul for not campaigning as a more hardcore libertarian, a charge that has been echoed with some frequency lately in publications sympathetic to the foreign policy views of Ron Paul. With respect to the diversity of opinion out there, and with the intimate knowledge that libertarians are more difficult to herd than wet cats during a catnip binge, allow me to suggest a different tool for thinking about the issue: Earl Weaver.

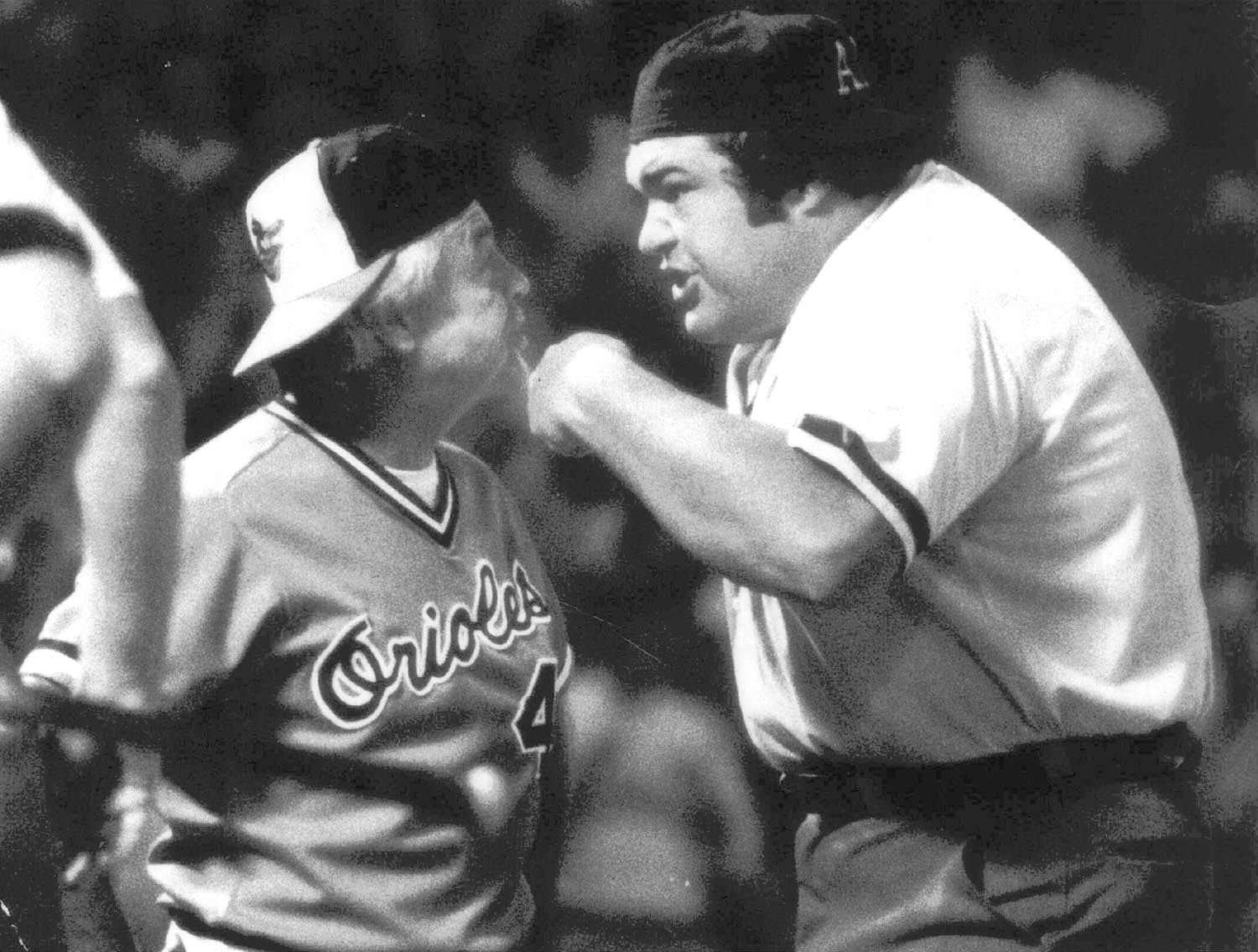

Who was Earl Weaver? One of the greatest managers in baseball history, a Hall of Famer who won one World Series (though it shoulda been more), four pennants, and six division crowns with the Baltimore Orioles from 1968-1986. While known by the casual fan as being the most comical of the 1970s' many umpire-hating rageaholics, and steward of arguably the best defensive units of all time, Weaver is also famous among non-baseball managers for his singular, utilitarian approach to appreciating and managing talent.

Here's how Jeff Burd put it in the Baseball Research Journal:

Weaver credits his ability to evaluate talent with the epiphany he experienced when he realized he would never play in the majors. In [a 1979] Time article, he said, "Right then I started becoming a good baseball person, because when I came to recognize, and more important, accept my own deficiencies, then I could recognize other players' inabilities and learn to accept them, not for what they can't do, but for what they can do."

Italics mine. As Bill James elaborated in his eponymous guide to baseball managers:

If [a player] can't hit a breaking pitch, you don't play him against Bert Blyleven [who had the best curveball in the game]. If he can't run, you pinch-run for him—but you don't let that stop you from developing what that player can do. It's the things that players can do that will win games for you.

Now, managing baseball players and evaluating politicians are not quite the same thing, and being too quick with embracing a least-worst strategy in electoral politics can quickly get you to unhelpfully anti-libertarian places like enthusiastic support for George W. Bush or Richard Nixon. But for all of Sen. Paul's real and postulated deviations from the libertarian script (pretending for the moment that such a fixed thing exists), when you focus instead on the libertarian-friendly things a President Paul still might plausibly accomplish, it's pretty easy to turn that frown upside-down.

That goes first of all to the area that Ron Paul fans hit the son hardest: foreign policy. Here's what Paul said in New Hampshire last week:

"The other Republicans will criticize the president and Hillary Clinton for their foreign policy, but they would just have done the same thing — just 10 times over," Paul said on the closing day of a New Hampshire GOP conference that brought about 20 presidential prospects to the first-in-the-nation primary state.

"There's a group of folks in our party who would have troops in six countries right now, maybe more," Paul said.

I predict that after 10 more months of that kind of talk, quite a few currently disillusioned anti-war libertarians will be singing a somewhat different tune. Of the 19 potential GOP candidates who visited New Hampshire this weekend, there were basically 18 hawks and one Rand Paul. Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Florida), arguably the most knowledgeable and qualified of the interventionists currently showing a pulse at the GOP polls, was even more gung-ho about bombing Libya than Hillary Clinton; Rand Paul might be the only major-party candidate able to convincingly make the opposite case.

The president of the United States has unusually wide latitude to make decisions about foreign policy and war. Even with Paul's refreshing emphasis on Congress's constitutional responsibility for the war-making power (which itself would mark an executive-branch restraint not seen in my lifetime), he would certainly be the least interventionist president since at least Ronald Reagan, and perhaps since Herbert Hoover.

Who was the most influential opponent to U.S. intervention into Syria in the fall of 2013? Rand Paul. I may not fully understand, let alone agree with, the senator's position supporting a limited bombing campaign against ISIS (see an extended foreign policy Q&A I conducted with Paul from our January issue), but he has managed to mainstream intervention-skepticism within the GOP in a way that was just not conceivable before he came along.

As for resisting the post-9/11 encroachment on American civil liberties, Paul has no real peer in either party. This exchange on civil liberties between the senator and I, from September 2013 but published here for the first time, depicts someone knowledgeably concerned not just with the underlying issue, but with how political power corrupts even libertarian instincts:

Rand Paul: People are amazed when I tell them that their visa records are not protected by the Fourth Amendment. And frankly that's the other thing that the FBI said in their drone thing, the NSA thing, when I went and asked about this. No records—this is really probably consistent with where the court is—no third-party records are protected by the Fourth Amendment at all. And that's wrong; we made the wrong decision, and I think because of technology, when the Supreme Court revisits it, I think they're going to restrain. They may not go as far as I want to go, but I tell people all the time, your visa records can tell whether you gamble, you smoke, whether you drink, whether you go to a psychiatrist, what medicines you take, because a lot of us put everything on our Visa cards. You can tell probably what medicines I take because I probably put it on my Visa card. You can probably figure out the pricing, and you can probably backtrack and figure out what medicines I take.

And that is an invasion of privacy, a huge invasion of privacy, and it's not any less mine because I let Visa hold my records. In fact, it's one of the biggest problems of the PATRIOT Act, and where people get confused is, they gave liability protection to all the telephone companies; it was a huge mistake. Even though I don't like lawsuits, and I don't like all the stuff that goes on that inhibits doing business, you should never give them liability [protection], because now they don't care about my privacy, they don't care about my contract.

Q: Which Obama flipped on in early 2008.

RP: Um, as president—he actually voted the other way, right, as a Senator?

Q: Yeah, but he changed position before the election after he'd already sort of secured the nomination against Hillary, he was like "Well, maybe I've changed my mind."

RP: It worries you because then you think, gosh, people really voted for something so diametrically opposite of what they got. And did he really change or was he always just sort of this person who didn't have that much respect for civil liberties and he voted that way because he thought that's what people wanted in his district?

Q: It's a great question. Because he did speak convincingly about this stuff.

RP: I think it would be the exception rather than the rule, and I'm not sure I could tell you which president actually stayed true to believing, that power corrupts and that it needs to be limited. I use the Lincoln quote, where he says if you want to test a man's adversity give him power, you know. Many men can stand adversity, but few can stand the test of power. And that's, I think, really what happens. It's that, and they believe in their own goodness.

If Rand Paul were to somehow wind up as president, and then conduct a 180 on civil liberties, it would be one of the biggest and most surprising con jobs in the modern history of American politics.

The libertarian tendency in American life and politics continues to grow in ways that frequently outpace even the biggest optimist's expectations. The 2nd Amendment was finally enshrined as an individual right. Recreational marijuana has been legalized in four states and the District of Columbia, with many more to come. Gay-marriage recognition from government is all but codified. And at long last, criminal justice reform has come tantalizingly within grasp, thanks in no small part to the leadership of Rand Paul. On the latter point especially, the amount of potential good that having a libertarian-friendly executive atop the federal law enforcement apparatus is vast.

There is no single right way to look at politics, or a politician, or an election. It's also important to remember, as Jeffrey A. Tucker reminds us here, that "People who invest themselves in the presidency somehow never come to terms with the reality that under the democratic nation state, no man or woman is a dictator." In other words, on that still-largely-unthinkable chance that someone genuinely influenced by libertarian views ascends to the White House, it's just not gonna be Libertarian Christmas every day. There's a deep state, a bureaucracy, and a country, that still requires constant convincing.

For the next 15 months at least, that project of persuasion will, in my judgment, be advanced by having a libertarianish "constitutional conservative" in the news every day campaigning for president against the likes of Marco Rubio and Hillary Clinton. At least I think Earl Weaver would have thought so.

Show Comments (43)