The Citizens United Backlash Threatens Basic Rights

Censoring corporations is effectively censoring ourselves.

First there was Bush Derangement Syndrome – a loathing of George W. Bush and his policies beyond all reason. Then came Obama Derangement Syndrome, which combines the fury of BDS with outlandish conspiracy theories. Now we see a new affliction: Citizens United Derangement Syndrome – CUDS, for short.

CUDS is the most dangerous, for three reasons. First, derangement over a president ends when his administration does. Second, CUDS has gained more steam. Efforts to impeach Bush went nowhere. The same is true so far for Obama. But ostensibly serious people in positions of genuine power truly want to amend the Constitution to overturn Citizens United.

And third: Some want to go much further than that.

A quick refresher: Once upon a time a private group, Citizens United, made a political film called Hillary: The Movie. The group wanted to run TV ads for the movie and air it during the 2008 election season. But since the film was partly underwritten with corporate money, under the law in effect at the time this was forbidden. So Citizens United sued.

The case worked its way up to the Supreme Court, where Chief Justice John Roberts asked if the law also could prohibit the publication of a political book.

Deputy Solicitor General Malcolm Stewart, representing the government, said yes – the government "could prohibit the publication of the book." Fred Wertheimer, president of Democracy 21 and former head of Common Cause, agreed: A book urging the election or defeat of a candidate "can be banned." A five-justice majority on the court quite correctly recoiled at this, and concluded that corporations and unions could spend money to speak their minds about candidates.

The 2010 ruling produced a firestorm of outrage that continues to burn. Last week Illinois became the 14th state to endorse a constitutional amendment aimed at reversing Citizens United. Resolutions in 20 more have been introduced; some are still pending.

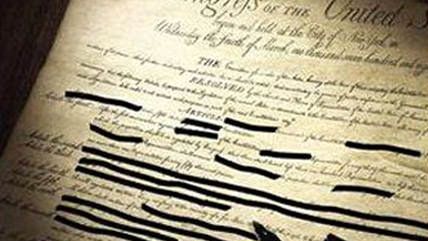

Some of the resolutions stipulate simply that money is not speech and that states may regulate campaign financing. This is problematic enough, as the case history shows. Yet other measures – including some that have passed – go much further.

They assert that corporations have no constitutional rights, period (Arizona); that the constitution protects "free speech and other rights of the people, not corporations" (Florida); that the Bill of Rights applies to "individual human beings" only (Illinois); that the First Amendment does not apply to corporations (Iowa); that the U.S. should "abolish corporate personhood" (Kentucky); that constitutional rights are "rights of human beings, not rights of corporations" (Montana); that constitutional rights "are the rights of natural persons only" (Minnesota); and so on.

Just so we're clear: This would strip newspapers, magazines, television shows, and book publishers of First Amendment protection – meaning the government could tell them what to print or say, and what not to. The same would apply to universities. It means the government could order advocacy groups such as NARAL and the Sierra Club to support legislation they oppose, or vice versa. If a legislature wanted to make charitable organizations like the American Cancer Society take dictation, it could. Ditto for unions. And so on.

Of course, some of the resolutions would strip corporations not only of their First Amendment rights but of all rights. As the Cato Institute's Ilya Shapiro explains, that would include the right against unreasonable search and seizure: The "police could search everyone's [work] computer for any reason, or for no reason at all." The corporate right to property would disappear as well: "The mayor of New York could say, 'I want my office to be in Rockefeller Center, so I'll just take it without any compensation.' " And while critics of Citizens United claim (incorrectly) that it overturns a century of precedent, they are trying to overturn two. The Supreme Court first recognized corporate personhood in 1819.

This is lunacy.

Moreover, the hostility to corporations that drives this derangement is curious. In a broad sense, corporations represent almost a communitarian ideal: They are groups of people who have come together voluntarily to pursue a collective interest. The government can put a gun to your head and command you to serve it. But you go to work for Google only if you choose to.

And in a legal sense, there is a very good reason for corporations to have certain rights. As Shapiro explains, they do so "not because they are corporations, but because they are composed of rights-bearing individuals." It is strange to think individuals should "lose all their rights" merely because "they come together to work in unison." Yet that is where some of those suffering from CUDS would have the country go.

The resolutions and petitions to strip corporations of their First Amendment rights, or all rights, allow only two possibilities. One is that their supporters have not given any serious thought to what they are advocating. The other is that they have. Neither is a comfort.

This article originally appeared in the Richmond-Times Dispatch.

Show Comments (166)