Uvalde Cop's Acquittal Shows Why It's Hard To Criminalize Failing To Stop a Mass Shooting

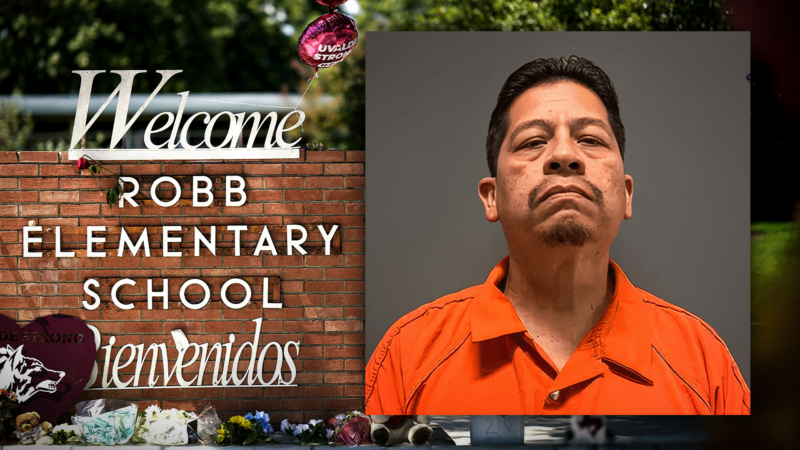

A Texas jury found Adrian Gonzales not guilty of endangering children by failing to confront the gunman at Robb Elementary School.

Adrian Gonzales was the first police officer to arrive at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, on the day a gunman murdered 19 students and two teachers there. Gonzales, who worked for the school district, therefore became a special target of public anger at the manifestly inadequate police response to that horrifying 2022 attack.

Although hundreds of officers were involved in that response, Gonzales is one of just two who faced criminal charges in connection with the shooting, along with his boss, Pete Arredondo, the district's police chief. On Wednesday, a jury in Corpus Christi acquitted Gonzales of the 29 child endangerment charges against him, illustrating the difficulty of treating the failure to stop a mass shooting as a crime.

Those 29 counts were tied to the 19 fourth-graders who were killed and 10 more who survived the shooting. Prosecutors alleged that Gonzales knew the location of the gunman before he entered the school but did not even attempt to intervene until it was too late. That failure, they said, qualified as 29 state jail felonies, each punishable by up to two years behind bars. But their case entailed a novel application of a Texas law that is ordinarily deployed against parents or other caregivers who endanger children.

Article 22.041(c) of the Texas Penal Code applies to someone who "intentionally, knowingly, recklessly, or with criminal negligence, by act or omission, engages in conduct that places a child" in "imminent danger of death, bodily injury, or physical or mental impairment." The case against Gonzales hinged on acts of omission. But under Texas law, "an omission is not any kind of a crime unless there's a specific duty to act," notes Sam Bassett, a former president of the Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers' Association.

To establish that Gonzales had a specific duty to act in this situation, prosecutors cited Article 6.06 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure. "Whenever, in the presence of a peace officer, or within his view, one person is about to commit an offense against the person or property of another," that provision says, "it is his duty to prevent it." The prosecution also cited Article 6.05, which says "it is the duty of every peace officer, when he may have been informed in any manner that a threat has been made by one person to do some injury to himself or to the person or property of another…to prevent the threatened injury, if within his power."

During his closing argument on Wednesday, defense attorney Jason Goss said his client's conduct did not fit the terms of Article 6.06 because Gonzales "never saw the shooter" and was "never in the presence of the shooter." As Special Prosecutor Bill Turner told it, that was precisely the problem: Gonzales should have been "in the presence of the shooter," whom he failed to pursue, confront, or impede. But as Goss noted, "that's not what this law says."

The law "doesn't say you have to go and find yourself and make yourself be in the presence" of an assailant, Goss told the jurors. "And I'm not trying to make any excuse about that, but the law is the law." Article 6.06 does not say "you have to go seek it out and make it happen in your presence," he said. "The law is saying if it's happening right there, there's a duty."

If the gunman "wasn't in his presence," Goss added, Article 6.05 also does not apply. "He has a duty…to prevent the threat to do injury if [it is] within his power," he said. "So they have to prove to you beyond a reasonable doubt that it's within his power."

It is hard to say how much weight these arguments carried with the jurors, who deliberated for seven hours before finding Gonzales not guilty. But the defense argued that Gonzales did the best he could in confusing circumstances and that there was reasonable doubt as to whether he had enough time to react in a way that might have stopped the attack. That goes to the question of whether it was "within his power" to "prevent the threatened injury" as well as the question of whether he acted "intentionally, knowingly, recklessly, or with criminal negligence."

The defense argued that Gonzales had been unjustly singled out, noting that at least three other officers arrived seconds after he did but were not prosecuted for endangering children. And it does seem like Gonzales, whatever his lapses, became a scapegoat for the systematic failures that explain why the gunman was not directly confronted until 77 minutes after the assault began, when members of the U.S. Border Patrol Tactical Unit breached a classroom door and shot him dead.

Since "the monster who hurt those kids is dead," Goss suggested, prosecuting Gonzales served to satisfy a thirst for justice that otherwise might have been channeled into convicting and punishing the person who actually committed these crimes. "I can imagine wanting to put somebody in that chair because I can't put the monster that did that to my child in that chair," he said. "I can imagine putting pressure [on prosecutors], and I can imagine them responding to the pressure. And I can imagine them putting him in that chair, him and only him in that chair, to try to pay for the pain, to try to somehow…cover the immeasurable and the immense loss."

In the end, the jury did not think it was just or legally appropriate to hold Gonzales criminally liable for appalling acts of violence that he may or may not have been able to prevent. The Florida jurors who heard the case against Scot Peterson, a school resource officer who faced similar charges after the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, reached a similar conclusion.

In Parkland as in Uvalde, the police ineptitude extended far beyond a particular cop's inaction. But like Gonzales, Peterson was accused of a cowardly failure to intervene in accordance with his training. And like the case against Gonzales, the case against Peterson involved creative interpretation of a law that was not obviously applicable: Peterson was charged with seven counts of felony child neglect, which hinged on viewing him as a "caregiver," along with three counts of culpable negligence. The jury acquitted him of all charges in June 2023.

You might view these verdicts as further evidence of jurors' general reluctance to hold police officers responsible for misconduct, even when it involves the blatantly reckless use of deadly force. Because jurors tend to view cops as heroes who risk their lives to protect the public, they are not inclined to second-guess the decisions cops make in stressful situations, perhaps worrying about a potential chilling effect on law enforcement.

Goss invoked that concern during his closing argument, warning that a conviction would make officers less rather than more likely to take appropriate action against criminals. If "I see somebody running towards the school," he said, describing the possible reaction of a hypothetical cop, "I'm not going after 'em, because if I'm mistaken and it takes me to the other side of the building from where the shooter is, and then I can't understand or know where the shooter is, I can go to prison. I can get prosecuted." The message of a conviction, he said, would be: "Don't go in. Don't react. Don't respond. Stay on the perimeter."

Whatever you make of that argument, there is a notable difference between the omissions at the center of this case and the deliberate acts that occasionally result in charges against allegedly abusive cops. While jurors in the latter sort of cases might cut defendants extra slack in light of their status as police officers, Gonzales and Peterson both ended up in the dock only because of that status, which prosecutors said transformed their acts of omission into felonies.

One can reject that premise, as the juries in both cases did, even while criticizing the performance of both officers. Peterson was fired after the Parkland shooting. Gonzales was suspended along with the rest of the school district's police department after the Uvalde shooting and had officially left his job by the beginning of 2023. But professional failures, even egregious ones, are not necessarily crimes.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

If you can't do - teach.

If you suck at being a cop - transfer to a school department.

We always made fun of the person in uniform they kept around at my school. They were at least 200lb overweight and might have been born with down syndrome.

jury did right.

Hopefully, we'd get some broader social awareness or cognitive transfer or self-reflection on the whole frame-by-frame breakdown surrounding Ross and Renee Goo... aw, who am I kidding?

What in acquitting a coward, who loved to torture victims at traffic stops?

yes in acquitting a coward who loved to torture victims at traffic stops.

Yup. A criminal court is not the right venue to convict someone of being a fucking coward.

There was not just a systematic failure responsible for the non-intervention in Uvalde but a society-wide failure to accept responsibility for one's own self defense. Not mentioned in this article and analysis is the fact that parents who WERE willing to accept responsibility for reacting to the disaster were actively PREVENTED from doing so by the same cops who failed to do their jobs. Somehow American society has gone from every kid having a .22 at the age of six and learning how to handle it safely to: "guns are the problem, if we eliminate the guns we'll eliminate gun violence and gun deaths." Although those children did not deserve to die at the hands of a violently insane mass murderer, their parents certainly learned the wrong lesson from the failure of the cops to respond to the emergency. When gun-free school zones are the law, only violently insane mass murderers will have guns in schools.

When gun-free school zones are the law, only violently insane mass murderers will have guns in schools.

now do the '66 UTexas Tower shooting

How much does cherry-picking pay, lefty shit?

He and the other cops who blocked those who were willing to act should have been charged as accessories. Now he can't be, because "double jeopardy," and my cynical side suspects that charging him for failure to act himself was a deliberate ploy to produce that result.

I can see his duty if the killer is right in front of him knocking off kids, I can even be sympathetic some sort of best effort to prevent that he failed at.

What I cannot see is a limit to this interpretation. Does receiving a 911 call make every cop liable for the outcome or just those within 500m, 100m...what exactly?

If police are unaccountable, and have special rights in their roles, they are a problem, nothing more.

JS;dr.

JS;dr

Hmm, Reason supporting cops not being responsible. Got it.

Consistency~!

Not just not being responsible.

Not responsible for doing less in 77 min. than they want to convict other cops for doing in less than 1s.

Libertarian Politician Googles 'What Is The Absolute Dumbest Take Possible' Before Deciding What Side Of Issue To Come Down On

Good point. Spending over an hour blocking parents from trying to save their kids is OK but shooting at somebody hitting you with a car is a step too far.

Reason logic is special logic.

Hey ChapGHB, what oath did Officer Gonzales take when joining the force?

I...do solemnly swear...that I will faithfully execute the duties of the office...and will to the best of my ability preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States and of this State, so help me God.

I am confident Texas has laws against murder. It is amazing the categoric lack of valor these "men" mustered up that day. If they cannot be troubled to put themselves in harms way, with any vehicle for accountability, then their presence serves no purpose whatsoever.

Not defending theb efts normalization of mental health issues being good may help with things.

The person responsible is the shooter(s). As for the headline, that doesn't apply to the parents of shooters. And arguably load mouth dumbass conspiracy theorists who think there are crisis actors.

This was a prosecution error. The jury was correct that Gonzales had no legal 'duty to protect' even though it was his damned job. His real evil was that he actively prevented others from going in to do the job that he refused to do.

The families should spend the emit decade suing this prick into oblivion. Ideally keeping the cases separate, so as to bury him in process.

when members of the "*U.S. Border Patrol* Tactical Unit" breached a classroom door and shot him dead.

OMG! Are you sure the Mass-Shooters Van was pointed at the Border Patrol agents! /s

Gosh if only those nasty 'Border Patrol' agents would've waited too before firing! /s

When seconds count, cops are only an hour away.

"A Texas jury found Adrian Gonzales not guilty of endangering children by failing to confront the gunman at Robb Elementary School."

It appears a jury has no problem with a cowardly law enforcement officer to do his sworn duty to protect the citizenry he's paid to protect and serve.

Yup.

That makes sense.

The anti-gun activists' and gun grabbers' constant refrain is that

citizensthe peasants don't need guns for self defense because they can call the cops. This episode soundly refutes that argument.