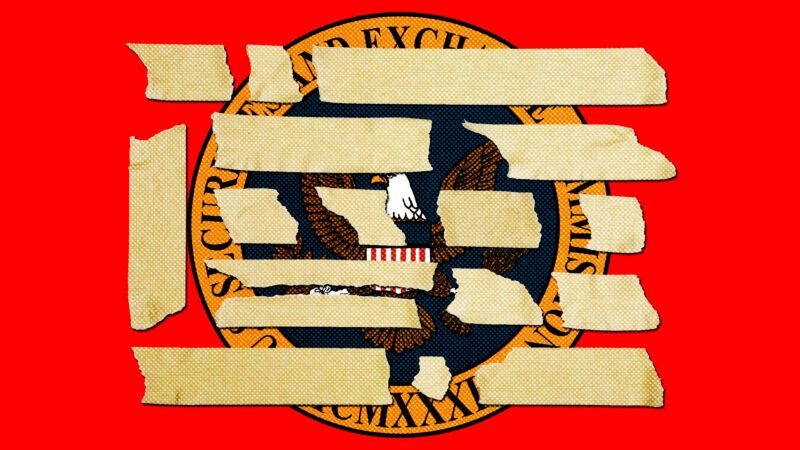

What Is the SEC Hiding?

To settle with the Securities and Exchange Commission, you must swear silence.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit will hear oral arguments regarding the Securities and Exchange Commission's (SEC) gag rule on Thursday. The rule flagrantly violates the First Amendment by prohibiting all defendants who settle with the SEC from publicly pleading their innocence in perpetuity.

Thomas Powell alleges that he was the victim of a high-pressure settlement process after being charged by the SEC: "I refused the settlement verbiage and specifically the gag order numerous times, but the SEC denied my requests and exerted time pressure, indicating that if I did not sign, they would take further enforcement action," he declared to the Court. In Powell v. SEC, petitioners ask the Court to vacate the SEC's denial of an earlier petition and order the Commission to remove the language imposing the gag from the rule.

Evaluating the SEC's complaints against Powell is impossible due to the gag rule. After alluding to the SEC's allegations against him, Powell's very next words are: "to which I can neither admit nor deny." The public is unable to judge for itself whether the SEC's actions against Powell are meritorious or meretricious, a waste of taxpayer dollars or responsible stewardship thereof, a reason to respect the agency or cause for outrage at executive overreach thanks to the gag rule.

The rule prohibits defendants who settle with the agency from ever publicly disputing the factual basis of the complaints made against them with its inclusion of a no-admit/no-deny policy. If that sounds unlawful, it's because it is. Margaret Little, counsel of record in Powell v. SEC for the New Civil Liberties Alliance (NCLA), a petitioner in the case, originally petitioned the SEC in October 2018 to remove the no-admit/no-deny language of the rule that unconstitutionally constrains defendants' speech. Little explains how the rule as written violates the First Amendment in no fewer than seven ways.

First, the gag rule imposes a prior restraint on speech by granting the SEC "unbridled discretion" over what speech defendants may engage in. Second, it does so for the rest of the defendant's life, constituting "perpetually mandated silence." Third, the rule regulates content both by penalizing defendants for articulating certain views about the details of the SEC complaint against them as well as for creating "an impression of a forbidden view of the complaint" in others. Fourth, the rule demonstrates its "raw unconstitutionality" by preventing defendants from uttering the truth except for the narrow carve out of judicial and testimonial proceedings. Fifth, the rule's provision that the defendant may not state his lack of admission to the complaint's allegations without also stating his lack of denial is "a raw assertion by the SEC of power to compel future speech." Sixth, citing the precedent of Legal Services v. Velazquez, the rule unconstitutionally conditions defendants' settlement "upon the surrender of his First Amendment rights"—which not even Congress may do. Finally, all of these previous violations of the First Amendment prevent defendants from pursuing one of the most important—and explicit—ends of the First Amendment: "to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."

The rule's speech controls only apply to the settler. The SEC gets "to describe these cases how they choose [while] defendants have to remain silent out of fear," explains Scott Shackford of Reason Foundation, the nonprofit that publishes this magazine and is a petitioner in Powell v. SEC. After settling, all that a defendant may say about the complaints made against him is "that he neither admits nor denies the allegations," as the SEC's rule specifies that the Commission "believes that a refusal to admit the allegations is equivalent to a denial."

The SEC denied NCLA's petition in January 2024. Writing for the majority, then-SEC Chair Gary Gensler said he was pleased to support the decision because permitting defendants from denying wrongdoing "undermines the value provided by the precipitation of the facts [and] muddies the message to the public." (Ironically, those who are found guilty are completely free to publicly plead their innocence.) Gensler lauds the SEC's no-admit/no-deny policy for having "served the public and the Commission well" insofar as it prevents the defendant from defending himself "in the press, and in the eyes of the public."

NCLA argued in its opening brief that the Court should vacate Gensler's opinion since it "offered no rational explanation for [the SEC's] decision," but was arbitrary and capricious, which violates federal law governing agency action. Unlawful though it may be, Gensler's opinion reflects the disregard for administrative procedure of the rule itself, which was published in the Federal Register in November 1972. After adding the paragraph implementing the no-admit/no-deny policy, then-Secretary Ronald F. Hunt stated "the foregoing amendment is declared to be effective immediately"—without public notice and comment—on the grounds that the amendment pertains "only to rules of agency organization."

The SEC's gag rule binds people outside the Commission; it is not merely a change in the Commission's organization, procedure, or practice. Federal rules may only go into effect without notice and comment when updating "methods of record keeping, how they schedule meetings, [and those things] considered to be housekeeping matters," Little tells Reason. By adopting a substantive rule without providing at least 30 days for public comment, the SEC violated the requirements of the 1946 Administrative Procedure Act, which requires agencies to "give interested persons an opportunity to participate in the rule making through submission of written data, views, or arguments with or without opportunity for oral presentation."

Commissioner Hester Peirce dissented from Gensler's opinion, arguing the gag rule "is unnecessary, undermines regulatory integrity, and raises First Amendment concerns." Pierce points to the Federal Trade Commission, which permits defendants to deny settled allegations, as proof that the evidentiary record "would stand on its own even if we permitted defendant denials." Moreover, she explains how the Commission's gag rule undermines its integrity and the public perception thereof by effectively saying, "Although we claim that these defendants have done terrible things, they refuse to admit it and we do not propose to prove it, but will simply resort to gagging their right to deny it." Finally, Peirce objects at length to the gag rule's vagueness, worrying that it even obliges defendants to stop others from saying things that cast doubt on the complaint's allegations.

Peirce describes settling as "the only economically viable option to resolve Commission enforcement actions" for many corporations, never mind individuals. In fact, the Cato Institute's amicus brief reports that 98 percent of those sued by the SEC settle. Consequently, media organizations can't report on whatever malfeasance the SEC may or may not be up to for want of primary sources. The Cato Institute experienced just this when it sought to publish a book about Bob's unfair prosecution by the SEC. "Bob" is a pseudonym; the Cato Institute can't disclose his real name in connection to the SEC complaint against him or poor Bob will be sued again. Because of the constitutionally outrageous gag rule, nobody will ever be able to hear and judge the merit of the SEC's complaints against "Bob" and those like him.

Congress itself may not curtail the First Amendment rights of citizens in the way that the SEC, a federal agency that derives its rule making powers from the legislative branch, has done for over 50 years. The Court now has the opportunity to remind administrative agencies to abide by the Administrative Procedure Act and to restore the constitutional rights of Americans.

Show Comments (8)