The DEA Wants To Ban Scientifically 'Crucial' Psychedelics Because People Might Use Them

The agency claims DOI and DOC have "a high potential for abuse" because they resemble other drugs it has placed in Schedule I.

You probably have never heard of 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine (DOI), let alone heard that it is commonly abused. Yet the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) wants to ban the synthetic psychedelic, a promising research chemical that has figured in more than 900 published studies, by placing it in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, a category supposedly reserved for drugs with a high abuse potential and no recognized medical applications—drugs so dangerous that they cannot be used safely, even under a doctor's supervision. Students for Sensible Drug Policy (SSDP), which defeated a previous DEA attempt to ban DOI in 2022, is determined to stop that move again.

On Tuesday, acting on behalf of more than 20 scientists, SSDP filed a prehearing statement objecting to DOI's placement in Schedule I. That step, SSDP notes, would impose "onerous financial and bureaucratic obstacles on researchers," since "obtaining a Schedule I license involves a daunting array of red tape and substantial costs, which can be prohibitive for many research institutions, particularly smaller labs and academic departments." SSDP also opposes the scheduling of another psychedelic, 2,5-dimethoxy-4-chloroamphetamine (DOC), that is covered by the same proposed rule, which the DEA published on December 13.

"DOI and DOC are important research chemicals with basically no evidence of abuse," says SSDP attorney Brett Phelps. "We are excited to fight on behalf of SSDP scientists so that they can continue the critical work they are doing with these substances."

Phelps is working with Denver attorney Robert Rush, who represents University of California, Berkeley, neuroscientist Raul Ramos. "The DEA's attempt to classify DOI, a compound of great significance to both psychedelic and fundamental serotonin research, as a Schedule I substance exemplifies an administrative agency overstepping its bounds," Rush says. "The government admits DOI is not being diverted for use outside of scientific research yet insists on placing this substance in such a restricted class that it will disrupt virtually all current research."

SSDP describes the two compounds as "essential research chemicals in pre-clinical psychiatry and neurobiology whose status as unscheduled compounds has made them de facto tools for researchers studying serotonin receptors." It says DOI in particular has been "a cornerstone in neuroscience research due to its high selectivity for the

5-HT2A serotonin receptor, a critical component in understanding and potentially enhancing the therapeutic effects of psychedelics."

Noting that "over 80% of the antidepressant drugs on the market affect the serotonin system," SSDP says scientists have used DOI to "map the localization of an important serotonin receptor in the brain critical in learning, memory and psychiatric disease." It adds that studies using DOI "have shown encouraging results in managing pain and reducing opioid cravings, offering a beacon of hope in the ongoing opioid crisis."

The DEA worries that DOI and DOC "have a high potential for abuse." Both drugs, it notes, "have been encountered by law enforcement in the United States," indicating their "availability for abuse." According to a review by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), it says, "individuals are using DOI and DOC for their hallucinogenic effects and taking them in amounts sufficient to create a hazard to their health."

Although DOI and DOC "are available for purchase from legitimate chemical synthesis companies because they are used in scientific research," the DEA concedes, "there is no evidence of diversion from these companies." Still, because "DOI and DOC are not found in FDA-approved drug products," it says, people who use them must be doing so "on their own initiative, rather than based on medical advice from practitioners licensed by law to administer drugs."

As the DEA sees it, any use of DOI or DOC is abuse by definition. "Anecdotal reports on the internet indicate that individuals are using substances they identified as DOI and DOC for their hallucinogenic effects," it notes, referring to accounts of DOI and DOC experiences on sites like Erowid. From 2005 through 2022, the DEA adds, the National Forensic Laboratory Information System (NFLIS) collected 40 reports of DOI and 790 reports of DOC—an annual average of about two and 46, respectively.

In 2022, the NFLIS collected nearly 1.2 million drug reports, so these compounds together would have accounted for something like 0.004 percent of the total. Unsurprisingly, the system's annual report does not even mention DOI or DOC. They apparently were categorized as "other phenethylamines," which together represented less than 0.2 percent of all drug reports.

Notably absent from the DEA's proposed rule is any evidence that recreational use of DOI or DOC is common, let alone that it has resulted in serious, widespread harm. "To date," the DEA admits, "there are no reports of distressing responses or death associated with DOI in medical literature." But "there have been three published reports, in 2008, 2014, and 2015, of adverse events associated with DOC including, but not limited to, seizures, agitation, tachycardia, hypertension, and death of one individual."

Because "DOI and DOC share similar mechanisms of action with and produce similar physiological and subjective effects…as other schedule I hallucinogens, such as DOM, DMT, and LSD," the DEA reasons, they "pose the same risks to public health." Although those risks, such as "hallucinogenic effects, sensory distortion, impaired judgment, [and] strange or dangerous behaviors," are mainly "borne by users," the DEA says, "they can affect the general public, as with driving under the influence." The fact that the DEA counts "hallucinogenic effects" and "sensory distortion" as "risks" speaks volumes about its attitude toward psychedelics and its refusal to acknowledge that they offer any potential benefits.

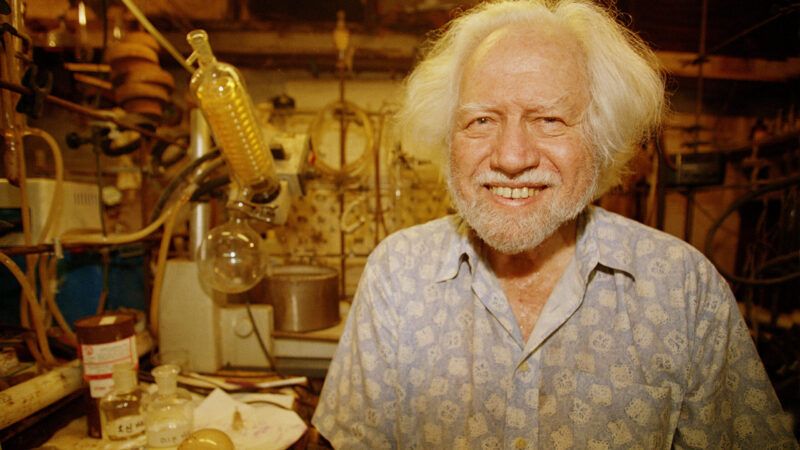

As the DEA notes, the psychoactive effects of DOI and DOC are similar to those of 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine (DOM, a.k.a. STP), a compound that the psychonautical chemist Alexander Shulgin first synthesized in 1963. In his book PIKHAL: A Chemical Story, Shulgin also describes his synthesis and exploration of DOI and DOC.

DOM has been listed in Schedule I since 1973. The DEA says adding DOI and DOC to that category is consistent with an HHS recommendation and U.S. treaty obligations.

Even as bureaucratic decisions go, this seems like a pretty thin basis for placing DOI and DOC in Schedule I. "The DEA admits that there are no cases in the medical literature of distressing events or death associated with the use of DOI," Phelps and Rush note in their prehearing statement. "The DEA admits that DOI is available for purchase from legitimate chemical companies because it is used in scientific research, and there is no evidence of diversion from these companies. The DEA admits that clinical studies with DOI have not been conducted in healthy human volunteers, and there is no data available from studies that evaluate the psychoactive and physiological responses produced by DOI in humans."

In the more than three decades since Shulgin first described the composition and effects of DOI in PIKHAL, the statement notes, the DEA counts just 40 seizures of the drug, with "no reported evidence" regarding "whether or how any of the seized DOI was used or abused." And in assessing DOI's "potential for abuse," the DEA "does not distinguish between use and abuse."

Under the Controlled Substances Act, the statement says, "the availability of psychotropic substances to manufacturers, distributors, dispensers, and researchers for useful and legitimate medical and scientific purposes" is not supposed to be "unduly restricted." Yet "HHS and the DEA failed to consider the impact that placement of DOI in Schedule I would have on ongoing and future scientific research on DOI." Phelps and Rush plan to present testimony from 15 researchers, including University of Kentucky neuroscientist Tanner Anderson, University of North Carolina chemical biologist David Nichols, and Imperial College London neuropsychopharmacologist David Nutt, who can attest to the scientific usefulness of DOI and DOC as well as the difficulties that placing them in Schedule I would entail.

SSDP and Ramos are seeking an administrative recommendation of a "finding and conclusion" that the DEA "has not met its burden" of showing that DOI and DOC have "a high potential for abuse." Among other things, the challenge raises the issue of whether treaty obligations can be met without placing the psychedelics in Schedule I and whether that decision would be "arbitrary and capricious," in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act.

If SSDP and Ramos do not prevail through the administrative process, they can challenge a scheduling decision in federal court. In the SSDP's press release, Rush alludes to "recent Supreme Court decisions," which include repudiation of the Chevron doctrine. That doctrine required that judges defer to a federal agency's "permissible" or "reasonable" interpretation of an "ambiguous" statute. Such deference had long been a source of broad leeway for the DEA, which relied on it in defending controversial decisions such as keeping marijuana in Schedule I—a classification that the Justice Department recently reconsidered, despite objections from the DEA.

Show Comments (24)