Black People Overwhelmingly Want To Maintain—or Increase—Police Presence. They Also Want Better Police.

The dominant media narrative has obscured much of the nuance here.

Multiple things can be true at once. It's a simple maxim. It's also unfortunately lost quite often in a news cycle that favors division and extremes. That dearth of complexity is especially apparent, it seems, when isolating demographic groups and analyzing where they fall on key issues.

A recent study published in the Journal of Criminal Justice provides a necessary reminder that, among other things, people are complicated. The general topic at hand: How do black Americans feel about policing?

Based on the press coverage over the last several years, I'd guess that a popular knee-jerk response to that question would be a straightforward, "Bad." But new data challenge that notion, finding that while black Americans do disproportionately fear cops, they express robust support for keeping—or even boosting—law enforcement presence and funding.

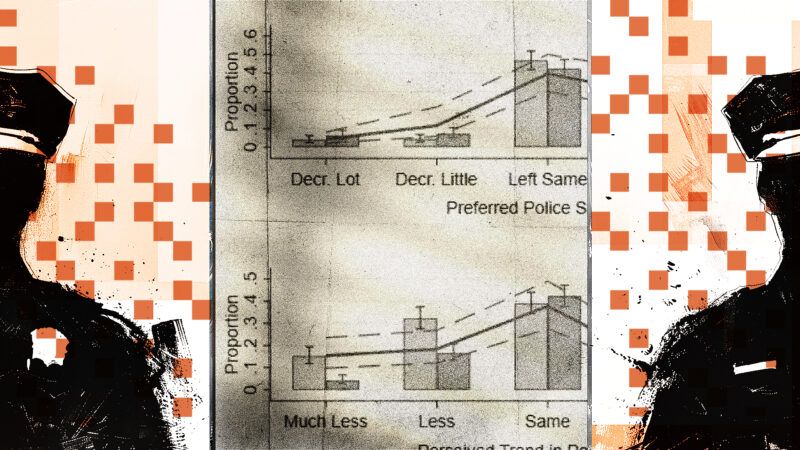

"Our key finding was that Black Americans preferred to maintain (or increase) police patrol and spending, and that this preference was not conditional on the described crime rates or policing reforms," write Linda Balcarová and Justin Pickett of the University at Albany, SUNY; Amanda Graham and Sean Patrick Roche of Texas State University; and Francis T. Cullen of the University of Cincinnati. "Most Black Americans reported that even if crime rates fell and even if there were no new policing reforms, they still wanted to maintain or increase police patrol and spending."

That latter bit is particularly important in the context of their hypothesis, which theorized that black Americans' support for police had been overstated in past research and was instead contingent in part on the impression that governments were implementing positive changes to policing. But that wasn't the case.

Yet the most interesting numbers, at least in my view, are the ones that show the wide chasm between black and white people's fear of police when compared to the relative agreement about what those people want to see in their communities.

It is well-established that black people are disproportionately afraid of cops, particularly in comparison to their white counterparts. Black Americans are reportedly more than five times as likely than white people to fear excessive force from police. What's more, a study by three of the same researchers—Pickett, Graham, and Cullen—found that 42 percent of black respondents were "very afraid" police would kill them sometime within the next five years. Only 11 percent of white respondents feared the same thing.

But in their more recent study, they found that such fear coexists, however counterintuitively, with that strong desire to keep or increase police presence and funding. According to their data, 81 percent of black Americans who say they are afraid or very afraid of cops want to maintain or increase police spending, while 78 percent of those respondents want to maintain or increase the number of cops in their communities. (As for the black respondents who said they are not afraid of police, support for maintaining or increasing police presence and spending were both over 90 percent.)

Interestingly, non-black respondents were more likely to express openness to decreasing police spending when crime is on the decline. The bulk of black respondents, however, expressed a consistent preference for maintaining or increasing funding notwithstanding the crime rate of the moment.

So what's going on here? A few things, I think.

The first: Just as the data make clear that black Americans are more likely to fear police, it is also plainly true that black people are disproportionately the victims of violence. It follows, then, that the people most impacted by crime are going to have strong feelings about abating it however possible. And while police are not always adept at solving crime—in 2022, for example, police cleared about 37 percent of violent offenses reported to them—their presence does have a deterrent effect on criminal activity, which also comports with basic common sense.

So too would that explain, at least in part, why their white counterparts are seemingly more open to decreasing funding levels depending on the context. A survey conducted by USA Today and the Detroit Free Press, for instance, found that 24 percent of black respondents in Detroit ranked public safety as "the biggest issue facing the city," emphasis mine, whereas only 10 percent of white respondents answered similarly. (A mere 3 percent of black respondents said that police reform was the most pressing issue, coming in last place.)

But in yet another reminder that multiple things can be true at once, that does not mean black Americans view police reform as a throwaway issue. They are significantly less confident in cops, less hopeful they'll be treated fairly, and their general support for reform is 20 percentage points higher than U.S. adults on the whole. In other words, many black Americans appear to be conducting a basic cost-benefit analysis: They know crime is a problem. They know police are part of the solution. And they know they want better police.

Much of this nuance is obscured in a media conversation that is often dominated by the polar fringes of the political spectrum and a failure to contextualize tragic events. Police brutality is unacceptable. No serious person would argue otherwise. And yet it also remains true that the odds of police killing anyone—regardless of race—is low and has gotten lower as the decades have gone on. Despite the viral claim to the contrary, those killings are not at a "record high." As I wrote last year:

A steep, decadeslong drop-off in police violence should be good news, no matter where you stand in this debate. It should be good news because fewer people dying is a good thing, and it should be good news because it shows some past reform efforts worked and can be learned from. It doesn't mean there isn't more work to be done.

But good news carries little currency in the current political climate. Positive developments are inconvenient when it comes to galvanizing support for your cause or getting clicks on the internet.

The conversation, like many conversations, is often driven by activists who claim to speak for entire communities—well-intentioned, yes, but incentivized to present a more dire picture than exists in reality.

That anyone can speak decisively for the "black community," or any broad community, is a ridiculous concept to begin with. There is no spokesperson for all black people, or all white people, or all women, and so on. There are nuances and differences among those groups, which might seem surprising today. It should be anything but.

Show Comments (34)