Can Free Markets Win Votes in the New GOP?

As the party grows more populist, ethnically diverse, and working class, will Republicans abandon their libertarian economic principles?

"Holy Miami-Dade, Batman," tweeted then–Politico reporter Tim Alberta on election night in 2020. Early returns had started rolling in, and the numbers from South Florida were not what people were expecting. President Donald Trump was dramatically exceeding his 2016 totals in the county's majority-Hispanic precincts.

Hillary Clinton had carried Miami-Dade by almost 30 percentage points four years earlier; Joe Biden took it by a mere seven percentage points en route to losing the state. "It was a bloodbath," one former Democratic Party official would tell The Washington Post.

Trump's strong showing in Miami-Dade was an indication that something strange was happening with partisan affiliations. Like most ethnic minorities, Hispanic Americans have long been viewed as a loyal Democratic constituency. But in recent years, that trend has begun to abate.

Back in 2002, journalist John B. Judis and political scientist Ruy Teixeira published The Emerging Democratic Majority, a book that "forecast the dawn of a new progressive era" powered by the organic growth of left-leaning demographic groups, including college-educated professionals and immigrants.

Now the pair have a new book, Where Have All the Democrats Gone? (Henry Holt and Co.), that sounds the alarm about "the cultural insularity and arrogance" driving blue-collar voters away from their party.

"We didn't anticipate the extent to which cultural liberalism might segue into cultural radicalism," Teixeira told The Wall Street Journal in 2022, "and the extent to which that view, particularly as driven by younger cohorts, would wind up imprinting itself on the entire infrastructure in and around the Democratic Party."

Among close political observers, the sense that the major parties are undergoing a major realignment has become pervasive. Whereas the GOP once was popularly associated with country club members and other relatively wealthy, highly educated constituents, the party is increasingly being referred to as the natural home of America's "multiethnic working class." The distinction is less about income, at least for now, and more about education: In 2020, Biden won handily among voters with a college degree, while Trump edged him out among those without one.

Meanwhile, the Democratic Party—once associated with labor unions and the relatively less well-off—is struggling with parts of its former base. A staggering two-thirds of white voters who didn't graduate from college went for Manhattanite Trump over Scranton-born Biden. The former vice president did earn the support of seven in 10 nonwhite voters, a respectable showing, but also an underperformance compared to Clinton's numbers in 2016 and Barack Obama's before that. Miami-Dade was not the only place where people of color swung toward Trump on the margins.

These shifts have caught the attention of political commentators and operatives of all stripes. Some, like Judis and Teixeira on the left, hope Democrats can stem their losses by moving to the middle on social issues. Others, including members of the "New Right," believe Republicans can expand their gains by moving leftward on economics. Hardly anyone seems to think there's a place for a principled defense of free markets and free trade.

If the parties are truly realigning, what does it mean for the future of American politics—and where does that leave libertarians?

It's Not the Economy, Stupid

In terms of pure electoral math, "nonwhites and working-class whites combine for a more than two-to-one advantage over whites with a college degree," Patrick Ruffini writes in Party of the People (Simon & Schuster). "In recent years, all the energy and growth in the Republican Party has come from this multiracial populist coalition."

Ruffini, a GOP pollster, is lauding the same phenomenon in his book that Judis and Teixeira are lamenting in theirs: Working-class whites have abandoned the Democratic Party in droves, while ethnic minorities are increasingly up for grabs. True, highly educated whites have swung toward the Democrats during the same period—and in 2020, that was enough to offset Biden's losses with nonwhite voters and deliver him to the White House. But because the share of Americans with a college degree is not likely to increase much more than it already has, this is questionable as a long-term strategy.

Given these changes, it has become fashionable on the right to demand that the Republican Party shed what is disparagingly referred to as its "free market fundamentalism"—the deregulation and international trade that the GOP championed for decades, in words if not in deeds. A whole ecosystem of nationalist-populist institutions, from think tanks to media platforms, has sprung up to push Republicans to embrace left-wing economics, which can include support for everything from tariffs to pro-labor regulations to industrial policy to targeted antitrust enforcement against disfavored companies.

Sen. Marco Rubio (R–Fla.) offered an example of this perspective in The American Conservative in June 2023. "We are living through a historic inflection point—the passing of a decades-long economic obsession with maximized efficiency and unqualified free trade," he wrote. "It's time to revive the American System," that is, "the use of public policy to support domestic manufacturing and develop emerging industries."

Some members of the New Right go even further, calling, in the most extreme cases, for an "American Caesar" strong enough to purge the land of its libertarian elements and forcibly reorient society to the common good. But even the more temperate voices generally see the idea of limited government as passé.

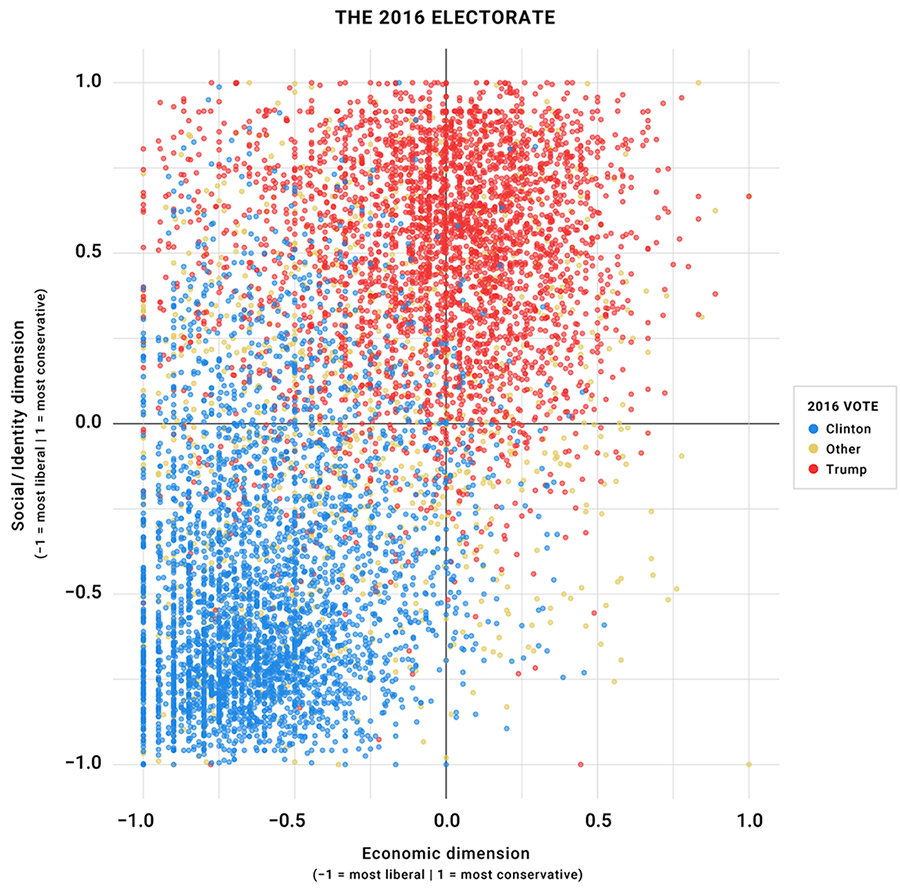

Advocates of such a turn often point to a widely circulated graph produced by the political scientist Lee Drutman after the 2016 election. It maps the electorate along two axes: economic left vs. right (along the horizontal) and social left vs. right (along the vertical). The upper right quadrant depicts consistent conservatives—those whose survey results are both socially and economically conservative, the vast majority of whom supported Donald Trump. The lower left quadrant depicts the inverse constituency, consistent progressives, the vast majority of whom supported Hillary Clinton. The lower right quadrant is allegedly for libertarians: economically conservative and socially liberal.

Whether that quadrant does a good job of actually capturing libertarians is a different question. Some of the social issues it uses to separate left from right are items that might indeed help distinguish between conservatives and libertarians, such as support for gay marriage and opposition to a Muslim ban. But others are items on which libertarians are not all in agreement with each other, such as whether abortion should be legal or whether illegal immigrants are good for the country. And on several—such as whether black Americans should receive special favors—you would expect libertarians, who tend to believe strongly in equality before the law, to come down on the "socially conservative" side. Taken together, this raises the possibility that quite a few self-identifying libertarians were coded as conservatives.

The economic issues index also is not perfect: Thanks to corporate welfare, a free marketeer might well agree with the supposedly progressive statement that our economic system is biased to favor the wealthy, for instance.

But the chattering classes have focused their attention on the upper left quadrant: people labeled socially conservative and economically progressive, sometimes referred to as the "populist" cohort. When Rubio et al. call on the GOP to move left economically, it is these voters they want to reach. Indeed, among those who flipped from supporting Obama in 2012 to supporting Trump in 2016, populists were overrepresented. It's natural to infer that Trump's willingness to stray from free market orthodoxy—his trade protectionism, for example—was the reason.

But does support for government intervention in the economy really deserve credit for landing our 45th president in the White House? Perhaps not. Look again at the four quadrants: The graph depicts a clear positive correlation between social and economic conservatism, and most people who voted for Trump also said they support free markets and free trade.

Both Party of the People and Where Have All the Democrats Gone? suggest it's social issues that are driving the realignment. In other words, working-class voters didn't rush into the arms of Trump because they saw him as an economic populist; they fled the Democratic Party because they saw it as a bunch of cultural radicals. It's the obsession with stating your pronouns and the perception that Democrats are soft on crime, not the economy, stupid.

"You're going to tell all white people in this country they have white privilege and we're a white-supremacist society?" Teixeira told the Journal. "And that we're all guilty of microaggressions every day in every way? Not only is this substantively wrong in my opinion, but as politics it's batshit crazy. You can't win if people think that's where you're coming from."

Ruffini concurs. Swing voters "are hardly New Right ideologues, espousing a combination of hard-left economic views and hard-right cultural views," he writes. "The key point about these voters is that they are only slightly off-center in their views on either dimension, hardly good recruits for a new ideological vanguard." Nonetheless, of the two, he believes "cultural questions are more and more central to how people vote these days."

This is reflected in a poll of Trump supporters commissioned by the Ethics and Public Policy Center just after the 2020 election. That survey did not find respondents consistently taking the New Right position. On some economic questions, such as whether trade with other countries helps or hurts America, they were split. On others, they expressed traditional free market views, such as that "government doesn't create wealth; people and businesses do." They strongly favored securing the southern border but were somewhat less sure how to handle those illegal immigrants who are already here. More than half believed that "climate change is real but science and technology developed by the private sector and government can help make its effects less severe," a refreshingly middle-of-the-road stance.

When it came to cultural grievances, however, the poll found overwhelming agreement: 89 percent of respondents believed that "Christianity is under attack in America today," 90 percent fretted that "Americans are losing faith in the ideas that make our country great," 92 percent thought that "the mainstream media today is just a part of the Democratic Party," and 87 percent worried that "discrimination against whites will increase a lot in the next few years."

Note that the moral questions of yesteryear, such as abortion and school prayer, are no longer central. Instead, GOP voters appear to be united around issues of culture and identity.

When people on the left discuss how on Earth Donald Trump managed to get elected president, they tend to assume that racial resentment was at work. When people on the right tackle the same question, they usually insist it was an uprising by blue-collar voters who felt "left behind" by our modern, globalized economy.

In The Overlooked Americans (Basic Books), Elizabeth Currid-Halkett, a professor of public policy at the University of Southern California, casts doubt on both those explanations. Her conclusion is that rural Americans who gave their votes to Trump "supported him for a wide range of reasons that had nothing to do with economic grievance or racism."

Currid-Halkett's research shows that on metrics from median income to homeownership to unemployment, rural America is actually doing quite well—especially compared to the prevailing narrative. By one measure, income inequality was higher in urban counties than in rural ones in 2019.

"For the most part, the people I interviewed also didn't feel particularly left behind," she writes. "As a man from Missouri who asked to remain anonymous remarked, 'The truth is, Elizabeth, we don't feel left behind. We want to be left alone.' He meant by the government and the media, which he felt encroached on his way of life." Later in the book, she summarizes the position of rural Americans as follows: "They don't want to feel looked down upon because of their lack of education or their belief in God….They don't want to be canceled for inadvertently saying something 'unwoke.'"

These voters were clearly turned off by the behavior of Democratic elites rather than turned on by Trump's economic agenda. Similarly, a distaste for white Christian identity politics, not a strange new predilection for left-wing economics, may be what's pushing highly educated voters away from the GOP.

"It used to be fashionable for country-club Republicans in [wealthy suburban communities] to say that they were 'fiscally conservative and socially moderate,'" Ruffini writes. "Now most of the rank-and-file voters who describe themselves this way have another name: Democrats."

'I Don't Want To Pay Taxes'

Those who saw nonwhite voters as a permanent Democratic constituency miscalculated on a number of points. For one thing, they failed to appreciate that black and Hispanic Democrats were always more conservative on social issues than their white peers within the party. "Many Black voters hold socially conservative positions on abortion and LGBTQ issues consistent with their higher levels of religiosity," Ruffini writes. They have historically voted blue despite, not because of, the party's cultural stances.

For another thing, America is extremely good at assimilating immigrants into the larger culture. Research from the Cato Institute's Alex Nowrasteh finds that second- and third-generation Americans are hardly distinguishable, politically and ideologically, from those whose families have been here longer. This is one of the reasons the so-called great replacement theory advanced by right-wingers such as Tucker Carlson was always so suspect: Even if the Democratic Party were trying to "import" left-leaning voters from developing countries, it would have no way of keeping them on the left.

"When a group moves from the margins and into the mainstream of American life," Ruffini writes, "history provides ample proof that their politics change to match their newfound social station. After World War II, the children of nineteenth-century immigrants to the United States moved to the suburbs, married across ethnic lines, went to college, and saw their economic fortunes rise. In doing so, they joined a Republican Party many of them had formerly shunned."

The same thing is happening today. Ruffini estimates that, between 2012 and 2020, Hispanics shifted 19 points, African Americans shifted 11 points, and Asian Americans shifted 5 points toward the GOP.

It's not clear Republicans need to embrace leftist economics to win over these groups. Immigrants are highly entrepreneurial, starting their own businesses at a significantly higher rate than does the native-born population. And Hispanics have seen particularly fast-paced income growth in recent years. "They are making it in America," Ruffini writes.

This has the potential to make such constituencies more receptive to free market messages. Party of the People includes an interview with Oscar Rosa, a Texas politico from one of the heavily Hispanic counties along the Rio Grande that swung toward Trump in 2020. "Today, Rosa sees a new wave of Republicans," Ruffini explains. "They are younger and hungrier, able to see a way out of the poverty of their parents' and grandparents' generations."

"The son who's working away at the oil rigs," Rosa said, "who's making $150,000 but only keeping $100,000 after taxes, is like, I'm a freaking Republican. I am a Republican. I don't want to pay taxes."

One poll of Texas Hispanics found that their No. 1 problem with the Democratic Party was that it "supports government welfare handouts for people who don't work." Another poll found that majorities of both Hispanic Americans and working-class Americans believe that "most people who want to get ahead can make it if they're willing to work hard." (In contrast, 88 percent of strong progressives thought that "hard work and determination are no guarantee of success for most people.")

The country as a whole is economically conservative in some important ways. A 2023 survey from the Center for American Political Studies at Harvard University found that a majority of registered voters think the U.S. government is spending too much money, and an even larger majority thinks it has taken on too much debt. Six in 10 say they would support a budget freeze.

Several New Right thinkers have recently become discouraged that more Republicans don't seem to be in a rush to tack left economically. In August, the Catholic journalist Sohrab Ahmari declared at Newsweek, "I Was Wrong: The GOP Will Never Be the Party of the Working Class."

"For half a decade following the rise of Donald Trump," he wrote, "I took a leading part in the effort to bring about a populist GOP." But since "the Republican Party remains, incorrigibly, a vehicle for the wealthy," he said, "I'm increasingly drawn to the economic policies of the Left—figures like Sens. Elizabeth Warren or Bernie Sanders, who…are willing to tackle the corporate hegemony and Wall Street domination that make daily life all but unlivable for the asset-less many."

Last February, political scientist Gladden Pappin (who was since installed as president of the Hungarian government's foreign policy research institute) published a long article at American Affairs titled "Requiem for the Realignment." Much like Ahmari, his complaint was that "neither conservatives at the Heritage Foundation nor 'based MAGA' advocates online have articulated a positive governing agenda that would use the power of the state to bolster the national industrial economy and support the American family." Pappin attributed Republicans' mediocre showing in the 2022 midterm elections to their reflexive invocation of Reagan-era talking points.

To the extent the GOP is hewing to the old playbook, though, it's likely because its base still largely supports economic freedom. Contra Ahmari, it's not just the donor class: According to a recent Gallup survey, 78 percent of Republicans think government is doing too many things that should be left to individuals and businesses, compared to just 18 percent who think government should do more to solve our country's problems. Among Democrats, those numbers are reversed—and at this supposed moment of realignment, the two parties are further apart on that question than they were 20 or 30 years ago.

Alas, it's not all good news. Americans may favor cutting government in theory, but once programs get going, they're damnably hard to eliminate in practice. Ruffini cautions that proposals to reform Social Security and Medicare are unpopular, especially among moderate swing-voter demographics. "The country may well need to reform entitlements to ensure their fiscal solvency," he writes, "but there are substantial political costs for Republicans who try to go it alone. Until and unless a bipartisan solution avails itself, Republicans would be wise to tread lightly."

Those political costs are real. A 2021 analysis by the pseudonymous blogger Xenocrypt found that many of the voters who fall into the upper-left (socially conservative, fiscally progressive) quadrant of Drutman's graph are only there because they don't want to see Social Security and Medicare benefits touched. Remove those two issues and an awful lot of supposed populists look like run-of-the-mill pro-market conservatives. No wonder so few Republican lawmakers are willing to die on the hill of entitlement reform.

Henry Olsen, a conservative Washington Post columnist who has more than earned his reputation as a shrewd observer of global politics, takes an even stronger view. Republicans "can't be the party of tax cuts to the exclusion of government spending," he says. "They don't have to be the protectionist party. But they do have to be the party that stops treating free trade as religious doctrine. And if the party doesn't want to do that, it will eventually find itself on the outs with its voters."

He doesn't think the GOP should reject markets entirely or "become indistinguishable from the Democrats," Olsen says. But he supports far more economic intervention than a libertarian would like. He thinks government has a responsibility to keep our food and drugs safe, to make sure workers aren't being exploited by employers, and to prevent "industry concentration" and the "unfair competition" that results. "A conservatism that wants to say 'no, no, no' to all of that," he concludes, "is a conservatism that wants to continually be a minority, and wants the country to move even further left than would otherwise be the case, because it forfeits the opportunity to define the center."

Recent elections do suggest a realignment is occurring, with more-educated voters increasingly identifying as Democrats and less-educated voters increasingly identifying as Republicans. Judis, Teixeira, and their allies hope the Democratic Party will adapt by moderating its cultural stances. Olsen and his allies hope the GOP will be more willing to compromise on economics. The result, as the ideological center of gravity on both sides shifts toward the middle, is that the major parties could start to look more and more alike.

This, in fact, is what the "median voter theorem" suggests should have been happening all along. That's the idea from political science and public choice economics that says, in essence, that elections will be won by whichever candidate is closer to the average member of the electorate—and that, as a result, candidates will tend to converge toward the center.

It's great if that means less mindless woke overreach by the left. But is there hope for economic freedom in such a future?

No More Pastel Shades

Libertarians needn't despair just yet. There may be tough times ahead for advocates of free minds and free markets, but then, what's new? We can take some solace in the knowledge that, while the median voter theorem might seem to have logic on its side, the reality has never been quite what the model would predict.

Part of the reason is that a major party that actually moves to the middle opens itself up to a third-party challenge from the outside flank. Another part is that it's hard to get people excited about milquetoast centrism. As Olsen himself put it in a recent column, "Historically, American voters have been attracted to parties and political figures with strong agendas and stronger personalities." They want "bold, unmistakable colors," to borrow President Ronald Reagan's metaphor, not "pastel shades."

A candidate with the conscience of his convictions who knows how to connect with voters can be a powerful force. At the same time, most regular Americans are not wedded to one ideological position, especially when it comes to complex economic policy questions: Their intuitions are often self-contradictory, and exposure to more information (like how much a proposed government program would actually cost!) can move the needle quite a lot.

All of which suggests that efforts at persuasion are not futile. We've already seen that Hispanic voters and other former Democratic constituencies exhibit an openness to free market ideas. The notion that left-wing positions are always better for working-class Americans is a gross oversimplification, after all. Just ask the many energy-sector employees in places like Louisiana and Texas how they feel about the Democratic Party's environmental agenda.

If we care about America's future, giving up on fiscal sanity is simply not an option. The entitlement system is going broke, whether or not it's politically popular to do something about it. Social Security and health insurance programs such as Medicare account for nearly half the federal budget, and as the ranks of retirees swell, they will consume an ever larger share. Debt service—that is, paying interest on the trillions of dollars Washington borrowed to finance its previous overspending—has exploded as interest rates have risen in the last couple of years. These problems are structural, and they will sink our economy eventually if they're not addressed.

Dismissive as he may be of libertarianism, Olsen understands this and has some ideas. "My view is that what the Republican Party needs to do is treat the budgetary crisis as a moral question as much as a political question," he says. "In large part, we have a deficit because we've been giving money, both through the tax code and through expenditures, to people who don't need it."

Olsen thinks the path forward is to eliminate tax breaks and subsidies that go to the rich. First and foremost, that means implementing a means test for entitlement programs: People bringing in hundreds of thousands of dollars in retirement income neither need nor deserve the same Social Security benefits as those who are just scraping by, he says. But it would also involve reforms like doing away with the tax break enjoyed by elite university endowments and ending farm subsidies. (Hilariously, "common-good conservative" Rubio, by insisting on handouts for his pals in the sugar industry, is a major obstacle on that last item.)

"I would never use the word austerity," Olsen says. "You're talking about a question of morals. The welfare state exists in theory to help people who need it overcome obstacles they can't bear on their own. The welfare state in practice—particularly because, for the left, the welfare state is meant to socialize life—gives money willy-nilly to people who need it or don't need it." That has to change, as libertarians and blue-collar voters alike should be able to agree. And approaching the budget with that goal in mind, Olsen says, "could go a long way toward closing the deficit."

An enduring tension in politics, Ruffini writes, is that "to get to 51 percent, the coalition needs to not entirely make sense." Yet there's no reason working-class and nonwhite Americans have to be at odds with those who strongly favor economic liberty. "When people hear about Republicans as a working-class party, they might assume this means an embrace of left-wing ideas about government spending, taxation, and regulation," he writes. "But the new Republican voters are not demanding this, and the current working-class realignment is happening under the umbrella of a pro-capitalist" GOP.

The Democratic Party has driven away droves of swing voters with its radicalism. The Republican Party has a choice about how to try to keep them. It can double down on the culture war, inflaming political tensions further. Or it can appeal to their aspirations; to their support for equality of opportunity, not equality of outcomes; and to the widely held belief that America is, and should remain, a place where people get ahead by working hard, not by looking to the state to solve their problems.

The second option is not only healthier for our country. Done well, it might just be smart politics.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Re-Examining the Realignment."

Show Comments (347)