Lawmakers and Unions Defend Burdensome Airline Regulations With Bogus Statistics

The world's largest union of pilots says this requirement is necessary for safety and not unduly burdensome, but its data are misleadingly cherry-picked.

The aviation industry is up in the air: There is a shortage of commercial airline pilots. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is considering whether to regulate smaller airlines out of existence. And Congress has struggled to pass a bill that would reauthorize the FAA through 2028. (Ahead of an October 1 shutdown, lawmakers agreed to extend the deadline to the end of the year.)

In each case, the argument is over safety: whether current regulations are sufficient, too strict, or not strict enough. Some feel that the rules governing major airlines protect passengers, and that any attempt to soften them would be catastrophic.

Some industry stakeholders, such as the world's largest pilot union, are using spurious statistics to make their case—and lawmakers on both sides of the aisle are going along with it.

On February 12, 2009, Colgan Air Flight 3407 from Newark to Buffalo crashed on approach to land. All 49 passengers and crew, plus one person on the ground, were killed. An investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) blamed pilot error.

In response, Congress passed the Airline Safety and Federal Aviation Administration Extension Act of 2010. Most consequentially, the law required pilots to log "at least 1,500 flight hours" in order to qualify for airline transport pilot (ATP) certification and be eligible to fly commercially. Previously, passenger airline pilots needed only 250 hours; most European countries still only require 250 hours as well.

At the time, the industry was skeptical. Smaller airlines worried that requiring so many more hours would cause a shortage of pilots. Roger Cohen, head of the Regional Airline Association, told NPR the new number was "arbitrary."

Just as predicted, the U.S. is now experiencing a pilot shortage. Geoff Murray, Daniel Rye, and Lindsay Grant of the consulting firm Oliver Wyman wrote in October 2023 that they expected the North American airline industry's pilot shortage to grow to 13,300 by 2032. But the authors also noted that "the tight supply has proved to be less dire in Canada. Based on current figures, we expect to see a mild pilot shortage this year, with pilot supply and demand converging in 2024." One factor in Canada's favor, they noted, was "the absence of the US rule that requires pilots to earn a minimum of 1,500 flight hours before being allowed to work for an airline."

That's bad news for passengers, though it's good news for existing pilots: Recent pilot contracts have included a 34 percent raise at Delta and a raise of as much as 46 percent at American Airlines. Clearly, when your services are more in demand, you can command a higher price for your labor.

The Air Line Pilots Association, International (ALPA), the world's largest pilot union, has a simple position on the pilot shortage: There is no pilot shortage.

"There are more than enough certificated pilots to meet demand here in the United States," claims the union's website. "The aviation industry is currently producing more pilots capable of immediately stepping into the right seat than there are jobs available to them." It notes that from July 2013 to March 2023, the U.S. generated nearly 64,000 ATP-certificated pilots while airlines only hired about 40,000, thereby generating a surplus of nearly 24,000.

Those numbers "suggest that every single ATP pilot will be an airline pilot, hence supply is greater than demand," counters Murray. "But data indicates that many pilots (about a third) who have ATPs don't fly for the airlines but rather fly the corporate/general aviation sector." In that case, ALPA's surplus shrinks nearly to zero.

Nevertheless, some lawmakers have stuck by the 1,500-hour rule. This summer, the House passed an FAA reauthorization bill that would allow aspiring pilots to count 250 hours of flight simulator training toward their 1,500 hour minimum. (Under current law, they can only count 100 simulator hours.) Sen. Tammy Duckworth (D–Ill.) declared that if the change was allowed, her colleagues would have "blood on your hands." To date, the Senate has not passed an FAA reauthorization.

Similarly, when Republic Airlines asked the FAA for permission to hire pilots with 750 hours from its own flight school (matching an exception granted to former military pilots, who also need only 750 hours), the agency declined, stating that this exception "is not in the public interest and would adversely affect safety."

Implicit in such warnings is the idea that the 1,500-hour rule is necessary to ensure flight safety. But there is little evidence that the beefed-up requirements have any bearing on safety—not now, and not when the rule was passed. "The FAA was unable to find a quantifiable relationship between the 1,500-hour requirement and airplane accidents and hence no benefit from the requirement," the agency determined in 2013. In 2010, NTSB Chair Deborah Hersman told a Senate subcommittee, "We've investigated accidents where we've seen very high-time pilots, and we've also investigated accidents where we've seen low-time pilots. We don't have any recommendations about the appropriate number of hours."

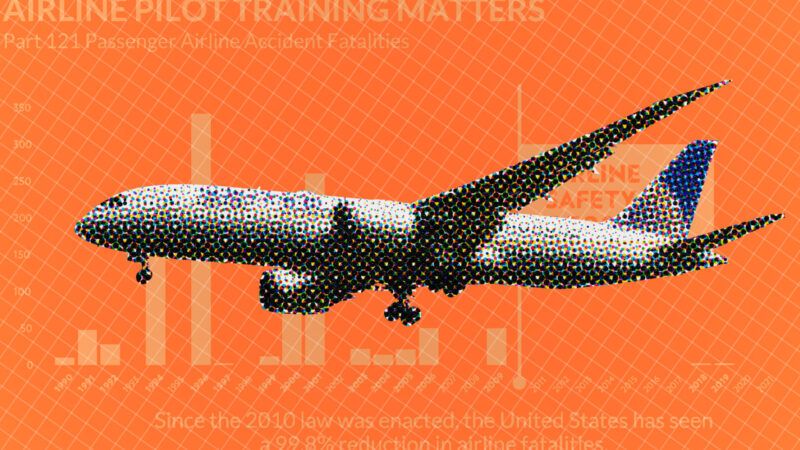

Some industry stakeholders credit the 1,500-hour rule with the near-absence of U.S. passenger airline fatalities since the Colgan crash. ALPA and its president, Captain Jason Ambrosi, often claim that since the law was passed, U.S. airline passenger fatalities have dropped 99.8 percent. The number appears on their website, in their press releases, in written Senate testimony, and in news articles that quote Ambrosi. It also showed up in a June letter to Sen. John Thune (R–S.D.), who had supported the provision to allow more simulator hours. ("Why," wrote Ambrosi, "when we have reduced the number of airline passenger fatalities by 99.8 percent since the current pilot training and qualification rules were implemented, would such a roll back even be considered?")

And it was cited on the House floor: During the June debate over the FAA reauthorization bill, Rep. Brian Higgins (R–N.Y.) claimed that "commercial aviation fatalities have decreased by 99.8 percent" since Congress "significantly increased the number of required flight training hours from just 250 to 1,500 hours."

In response to Reason's request for clarification, an ALPA spokesperson pointed to a bar chart on its website. The chart lists annual U.S. airline passenger fatalities since 1990, using the 2010 law as the dividing line. Before 2010, there are multiple years with 50 or more fatalities; there are no deaths in each year from 2011 to 2017 and 2020 to 2021, with tiny single-digit blips in 2018 and 2019.

The first problem with the chart is that the 1,500-hour rule didn't go into effect until July 15, 2013—meaning it had no bearing on the dearth of fatalities in 2011, 2012, and the first half of 2013. (And since the chart makes 2010 the dividing line, it obscures the fact that there were just two commercial airline deaths that year). Further, there are multiple years before 2010 with zero fatalities, including the two years prior to the Colgan crash.

The "99.8 percent" claim is also misleading. It doesn't refer to annual deaths, as that statistic would require at least 500 per year before the law and one per year after in order to show a 99.8 percent decline. Instead, ALPA appears to be comparing the total deaths from 1990–2010 to the total from 2011–2021. Not only does this compare a 20-year period to a 10-year period, but it elides the fact that not every crash is the result of pilot error—and even among those that are, the 1,500-hour rule would often have made no difference.

In fact, the pilots on the Colgan flight that spawned the rule each had more than 1,500 hours of flight time: Captain Marvin Renslow had 3,379 hours logged, while First Officer Rebecca Shaw had 2,244, of which 774 were in planes like the one involved in the crash. According to the NTSB's investigation of the accident, Renslow "experienced training problems throughout his flying career" and showed "continued weaknesses in basic aircraft control and attitude instrument flying." As a result, Renslow "would have been a candidate for remedial training," but "Colgan [Air] was not proactively addressing his training and proficiency issues."

Similarly, ALPA's data includes Alaska Airlines Flight 261 that crashed on January 31, 2000, killing all 88 passengers and crew. But the NTSB determined that crash was caused by mechanical failure. ALPA also includes American Airlines Flight 587, which crashed in Belle Harbor, New York, in 2001, killing 260 people. (ALPA's numbers do not include the September 11 attacks, as NTSB data excludes fatalities resulting from terrorism, suicide, or sabotage.) But while the NTSB did determine that Flight 587 was brought down by pilot error, the officer in question had 4,403 flight hours—nearly three times the current legal requirement.

The 1,500-hour rule would not have kept those negligent pilots out of their cockpits. But it can keep out skilled pilots who could alleviate a shortage.

Show Comments (97)