SCOTUS Will Decide When the Government's Social Media Meddling Violates the First Amendment

The justices agreed to consider whether the Biden administration's efforts to suppress online "misinformation" were unconstitutional.

On Friday, the U.S. Supreme Court stayed a preliminary injunction aimed at preventing federal officials from unconstitutionally interfering with content moderation decisions by social media platforms. At the same time, the Court agreed to decide the merits of the case, Murthy v. Missouri, during its current term. The stay will remain in place until the justices resolve that case, so the Biden administration meanwhile is free to resume contacts with social media companies that a federal judge and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit concluded were probably inconsistent with the First Amendment.

Justice Samuel Alito, joined by Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch, objected to the Court's "unreasoned" stay, saying the government had failed to show that it would suffer "irreparable harm" if the 5th Circuit's injunction remained in place while the case was pending. "Government censorship of private speech is antithetical to our democratic form of government, and therefore today's decision is highly disturbing," Alito wrote. "Despite the Government's conspicuous failure to establish a threat of irreparable harm, the majority stays the injunction and thus allows the defendants to persist in committing the type of First Amendment violations that the lower courts identified."

The case began with a lawsuit by the attorneys general of Missouri and Louisiana, joined by several social media users whose posts had been downgraded or deleted as "misinformation." They argued that such decisions resulted from relentless pressure by federal officials who were determined to suppress online speech they viewed as dangerous to public health, democracy, or national security. The plaintiffs said that pressure, which was accompanied by implicit threats of retaliation against noncompliant platforms, crossed the line between permissible government speech and censorship by proxy.

Last July, U.S. District Judge Terry Doughty agreed. Doughty issued a preliminary injunction, backed by a 155-page opinion, that restricted communications between several federal agencies and social media platforms. Last month, the 5th Circuit upheld the gist of Doughty's decision, although it narrowed the terms of his injunction and reduced the number of agencies to which it applied.

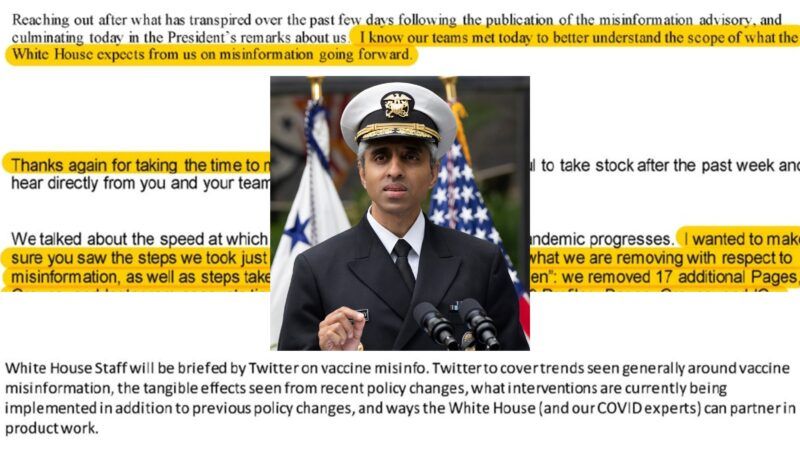

Under the 5th Circuit's injunction, the White House, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy's office, the FBI, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were forbidden to "coerce or significantly encourage social-media companies to remove, delete, suppress, or reduce, including through altering their algorithms, posted social-media content containing protected free speech." This month, after a rehearing requested by the plaintiffs, the 5th Circuit expanded that injunction to cover the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency.

The Biden adminstration asked the Supreme Court to intervene, saying the injunction placed "unprecedented limits on the ability of the President's closest aides to use the bully pulpit to address matters of public concern, on the FBI's ability to address threats to the Nation's security, and on the CDC's ability to relay public-health information at platforms' request." U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar rejected the plaintiffs' characterization of interactions between federal officials and social media companies regarding COVID-19 "misinformation," saying the ensuing decisions to delete posts, banish specific users, or modify content rules resulted from a collaborative process. "Rather than any pattern of coercive threats backed by sanctions," she said, "the record reflects a back-and-forth in which the government and platforms often shared goals and worked together, sometimes disagreed, and occasionally became frustrated with one another, as all parties articulated and pursued their own goals and interests during an unprecedented pandemic."

That "back-and-forth," however, included "requests" that were tantamount to commands. "Are you guys fucking serious?" Deputy Assistant to the President Rob Flaherty said in an email to Facebook. "I want an answer on what happened here and I want it today." Because Facebook was "not trying to solve the problem," White House COVID-19 adviser Andrew Slavitt told Facebook, the White House was "considering our options on what to do about it." On another occasion, Flaherty told Twitter to delete a parody account tied to one of Biden's grandchildren "immediately," saying he could not "stress [enough] the degree to which this needs to be resolved immediately."

According to Prelogar, such interactions did not amount to government-directed censorship. "It is axiomatic that the government is entitled to provide the public with information and to 'advocate and defend its own policies,'" she said. "A central dimension of presidential power is the use of the Office's bully pulpit to seek to persuade Americans—and American companies—to act in ways that the President believes would advance the public interest." Although "the government cannot punish people for expressing different views" or "threaten to punish the media or other intermediaries for disseminating disfavored speech," she said, "there is a fundamental distinction between persuasion and coercion."

Prelogar complained that the 5th Circuit had conflated the former with the latter. She said the appeals court could not cite "a single instance in which an official paired a request to remove content with a threat of adverse action." She also noted that "the platforms declined the officials' requests routinely and without consequence."

As the Biden administration sees it, coercion requires an explicit threat tied to a specific request, followed by imposition of that "consequence" when a platform rejects the request. The plaintiffs take a broader view of coercion, arguing that it can be inferred when public and private castigation is coupled with repeated references to presidential displeasure and the potential consequences of failing to meet the "responsibility" that administration officials insisted the social media platforms had to control "misinformation." Federal officials publicly said holding social media companies "accountable" could entail "legal and regulatory measures," new privacy regulations, "a robust anti-trust program," and reduced legal protection against civil claims based on user-posted content.

"The bully pulpit is not a pulpit to bully," the plaintiffs said in opposition to Prelogar's request for a stay. "The district court's findings and the evidence establish an extensive

campaign by federal officials in the White House, the Surgeon General's Office, the CDC, and the FBI to silence disfavored viewpoints on social media….To induce platforms to remove such content, White House officials resorted to a battery of harassing and menacing statements." The 5th Circuit's injunction should be left in place, they argued, because it "closely matches what the First Amendment already requires [federal officials] to do."

Alito, Thomas, and Gorsuch were sympathetic to that view. "The Court of Appeals agreed with the District Court's assessment of the evidence, which, in its words, showed the existence of 'a coordinated campaign' of unprecedented 'magnitude orchestrated by federal officials that jeopardized a fundamental aspect of American life,'" Alito wrote. "The Court of Appeals found that 'the district court was correct in its assessment'" that "'unrelenting pressure' from certain government officials likely 'had the intended result of suppressing millions of protected free speech postings by American citizens.'"

Alito said the administration's claim of "irreparable harm" from the 5th Circuit's injunction was based on nothing more than speculation that it might have a chilling impact on permissible government speech. Suppose, Prelogar said, the president "urges platforms not to disseminate misinformation about a recent natural disaster circulating online" and "the platforms comply." Or suppose "the President condemns the role that social media has played in harming teenagers' mental health, calls on platforms to exercise greater responsibility, and mentions the possibility of legislative reforms." Prelogar suggested that such statements might be construed as violating the 5th Circuit's injunction.

"It does not appear that any of the Government's hypothetical communications would actually be prohibited by the injunction," Alito said. "Nor is any such example provided by the Court's unreasoned order. The Government claims that the injunction might prevent 'the President and the senior officials who serve as his proxies' from 'speak[ing] to the public on matters of public concern.'" But "the President himself is not subject to the injunction," and "in any event, the injunction does not prevent any Government official from speaking on any matter or from urging any entity or person to act in accordance with the Government's view of responsible conduct."

Alito noted that "the injunction applies only when the Government crosses the line and begins to coerce or control others' exercise of their free-speech rights." He asked: "Does the Government think that the First Amendment allows Executive Branch officials to engage in such conduct? Does it have plans for this to occur between now and the time when this case is decided?"

Since the 5th Circuit's injunction is no longer in effect, we may find out. Ultimately, however, the Supreme Court needs to clarify not only the difference between "persuasion" and "coercion" in this context but also the point at which the government's influence on content moderation is so extensive that it is unconstitutionally "encouraging" speech restrictions.

Show Comments (72)