A Louisiana Man Was Jailed for Criticizing Police. A Federal Court Wasn't Having It.

The decision supports the notion that victims are entitled to recourse when the state retaliates against people for their words. But that recourse is still not guaranteed.

In July 2017, Louisiana woman Nanette Krentel was shot in the head and left to be incinerated as her house burned down around her. More than two years went by before anyone was arrested in relation to the murder.

It was not the alleged murderer.

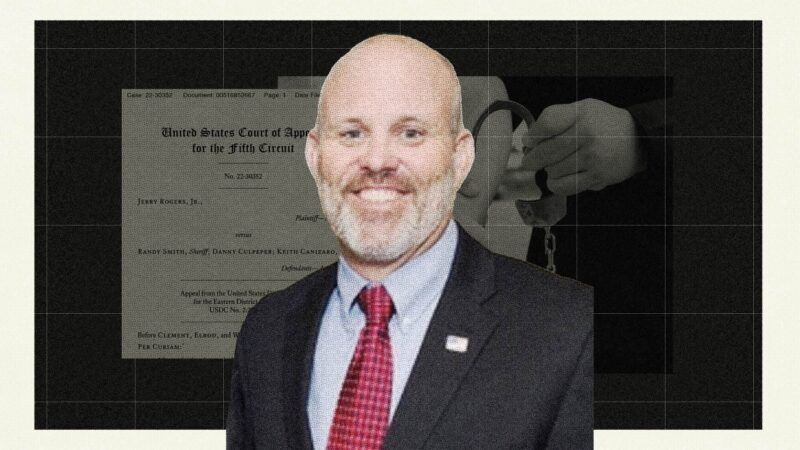

The sole arrest pertaining to Krentel's demise was that of a man who criticized the St. Tammany Parish Sheriff's Office's (STPSO) slow-going investigation of the case, which remains unsolved. If that sounds unconstitutional, it's because it is: On Wednesday, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit confirmed that Jerry Rogers Jr.'s suit against Sheriff Randy Smith, Chief Danny Culpeper, and Sgt. Keith Canizaro may proceed, as they violated clearly established law when they arrested him for his speech.

"This ruling is a lightning bolt that has struck three law enforcement officers who tried to stand taller than the United States Constitution," said William Most, who is representing Rogers, in a statement.

The decision buttresses the notion that victims are entitled to recourse when the government weaponizes the criminal justice system against people for their words. But getting that recourse is still not a guarantee.

Rogers, however, will finally be able to sue those officers. In 2019, the STPSO caught wind that he had expressed his ire for the lead investigator, Detective Daniel Buckner, whom Rogers characterized in an email as "clueless." In order to pore over his messages, the police obtained what was likely an illegal search warrant, as it listed the qualifying offense as "14:00000," which does not exist.

To arrest him, the police had to furnish a real crime, as opposed to an imaginary one, so they sought to leverage Louisiana's criminal defamation statute. Lawyers with the district attorney's office told them that would be illegal, as that law was long ago rendered unconstitutional as it pertains to the criticism of public officials.

The defendants were undeterred. They arrested, strip-searched, and detained Rogers. He was jailed for part of that day and then released on bond, and the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections ultimately declined to prosecute the case. But the primary goal was likely humiliation: Before he was booked, the police blasted out a press release about his arrest—which, according to Canizaro, was the only time he could remember the office following that particular order of operations. And the police filed a formal complaint with Rogers' employer, something they had also never done before.

"It is my sincere hope and prayer," says Rogers, "that this gives others strength and courage to never give up and continue to fight evil."

That he has had to wait almost four years for permission to sue over that retaliation is an apt indictment of qualified immunity, which requires victims of state and local government abuse to show that the violation of their rights was "clearly established" with meticulous exactitude in a prior court precedent. Though Rogers overcame that, the legal doctrine enables the government to file appeal after appeal, dragging out costly litigation for years.

This is not an uncommon tactic. Consider the case of William Virgil, who spent 28 years behind bars after two officers in Kentucky allegedly framed him for murder. The courts repeatedly sided with Virgil in his suit. And then, last year, he died as the state insisted on pursuing yet another appeal.

Rogers' arrest and detainment may seem like an obvious departure from the law. But whether or not similarly situated victims are able to find recourse depends in part on the jurisdiction and who happens to hear the case. Even within the 5th Circuit itself, the question isn't settled.

That murkiness is on display in the case of Priscilla Villarreal, a citizen journalist in Laredo, Texas, who often covers criminal justice issues and shares stories with her sizable Facebook following. Her irreverent commentary has earned her a strained relationship with the local police, who arrested and jailed her in 2017 for seeking information and publishing it, which is otherwise known as journalism. The stories that violated the law, they said, pertained to a Border Patrol agent who'd committed suicide and a family involved in a fatal car crash.

It was the Laredo Police Department that gave her the information she requested, and it was the Laredo Police Department that arrested her for publishing it. To jail her, the government cited an obscure Texas law that makes it illegal to seek nonpublic information from a civil servant if the seeker has an "intent to obtain a benefit." The benefit, the police said, was that she stood to gain more Facebook followers.

The only thing more absurd than the police leveraging that argument to arrest someone is that some of the most powerful judges in the country have bought into it. The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas gave those officers qualified immunity. The 5th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned that, with a forceful opinion written by Judge James C. Ho, who was appointed to the bench by former President Donald Trump. But in a rare move, the rest of the 5th Circuit moved to rehear the case, which suggests that a majority of the judges think Ho came to the wrong conclusion.

"Villareal's [sic] Complaint says that she 'sometimes enjoys a free meal from appreciative readers,…occasionally receives fees for promoting a local business [and] has used her Facebook page [where all of her reporting is published] to ask for donations for new equipment necessary to continue her citizen journalism efforts,'" wrote Chief Judge Priscilla Richman in dissent. "With great respect, the majority opinion is off base in holding that no reasonably competent officer could objectively have thought that Villareal [sic] obtained information from her back-door source within the Laredo Police Department with an 'intent to benefit.'"

But whether or not Villarreal or Rogers are entitled to freely exercise their First Amendment rights should not depend on if someone has previously bought them lunch, nor should it turn on how fraught their relationship is with local law enforcement.

Show Comments (40)