Turns Out 'Bidenomics' Means Top-Down Economic Control

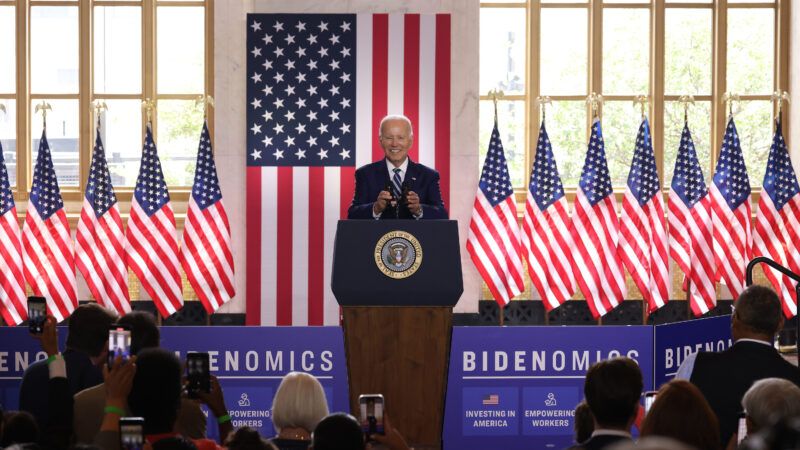

Joe Biden's big economic speech is a poor attempt at a branding exercise.

For the last two years, President Joe Biden has been crediting various supposed successes in the economy to "my economic plan." Now that plan has a self-referential name: "Bidenomics."

Biden appeared in Chicago this week to give a long-winded speech on his economic agenda. The basics will be familiar to anyone who has watched a Biden speech or read economic policy coverage for the last few years: Biden touted a playbook that consists of subsidies and spending, rules and regulations, unions and jobs. This was not an announcement of new policies or new ideas so much as a summary, and a name, for what he's already done.

Biden even recycled his old tagline, saying repeatedly that he intends to build an economy from "the middle out and the bottom up—not the top down." It's an ironic refrain from someone whose approach to economics is decidedly focused on top-down control.

Biden's economic success story is dubious by any measure. For instance, he touted recent plans to heavily subsidize semiconductor factories, arguing that these subsidies would both make America a bigger player in the world market for computer chips and deliver high-paying jobs to the heartland.

But the Biden administration's quest to fund semiconductor factories has hit a number of snags, including a lack of skilled workers and higher-than-anticipated construction costs. On several major projects, there are simply not enough workers to fill the jobs. Meanwhile, Biden has larded those projects with unrelated social goals, like child care. Even those with long experience in the semiconductor industry have criticized Biden's plans: Last year, Morris Chang, founder of the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), which is currently in the midst of building a chip plant in Arizona, warned that America's efforts to subsidize domestic production would be an "expensive exercise in futility."

In his speech, Biden also repeated a figure he's touted before—that those without college degrees would make an average of $100,000 to $130,000 working in chip-plant fabs. But even Biden's own advisers have hedged on the particular statistic: "It doesn't mean that every job is going to pay six figures," a senior Biden administration official told Time. "That's the average. When you aggregate all the jobs—the four-year degree jobs, the two years, the training certificates—you will get a number like $135,000…But of course it's a mix of jobs."

Many fab-plant jobs, in other words, particularly low-skilled work, will pay much less than the six figures Biden advertised. Graduates of quick chip-fab training programs, Time reports, typically earn about $43,000.

Biden's speech wasn't just about his administration's quixotic quest for semiconductor subsidies. He also ran through what amounts to the greatest hits, or misses, of his administration's economic agenda: "promoting competition" (presumably by waging a series of losing antitrust battles), pushing green energy (via poorly targeted subsidies that might make energy more expensive), promoting unions and union jobs (which will raise barriers to entry, lower productivity, and increase costs in ways that could lead to higher inflation). Bidenomics turns out to mean pursuing the policies he's already pursued, and putting his name on them.

Biden may be taking credit, but voters aren't on board. Inflation—the highest in four decades—has added about $768 in monthly costs to the average American household's budget, according to Moody's Analytics. It's ironic that Biden tried to convert his semiconductor subsidy program into what turned out to be a misleading story about high wages, because wage declines are at the root of America's economic pessimism. Persistent inflation, a substantial portion of which was caused by Biden's overspending, has resulted in a historic drop in real wages. Typical households now have less buying power than they did when Biden entered office. That's Bidenomics.

Indeed, the best way to understand Biden's speech is not as an announcement of new economic policy, but as a branding exercise in the run-up to next year's election. (A memo sent out in conjunction with the speech was authored by Biden's political messaging advisors, not his economic team.) Biden wants voters to understand that he's taking credit for the nation's economy. But according to polls from USA Today/Suffolk and Pew Research Center, majorities of Americans believe inflation is a major problem, and living in the country is too expensive. Voters understand perfectly well that this is Biden's economy—and they don't like it.

Show Comments (58)