Ohio Cops Raided Afroman's House Looking for a Dungeon Because of a Bizarre Confidential Informant Tip

All they found was some cool cars and clothes.

When sheriff's deputies in Adams County, Ohio, raided Afroman's house last year, they were looking for more than just marijuana, which the rapper is famously fond of. The deputies were searching for evidence of outlandish claims from a confidential informant that the house contained a basement dungeon.

The Adams County Sheriff's Office (ACSO) executed a search warrant on Afroman's house last August on suspicion of drug possession, drug trafficking, and kidnapping. Afroman was not charged with a crime, and the kidnapping angle was never explained. But now, public records obtained by Arthur West, a public records advocate, and provided to Reason shed more light on the raid, which has since led to a bitter legal battle between Afroman and the ACSO deputies.

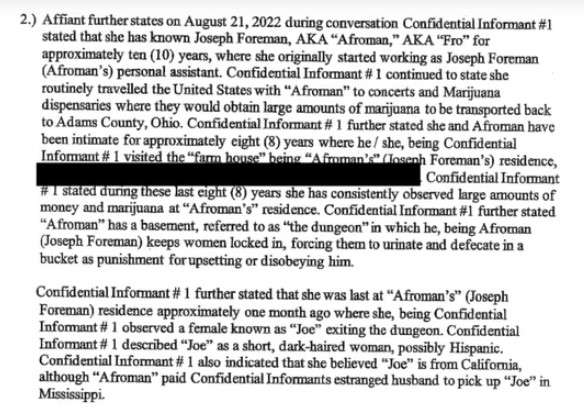

According to the search warrant affidavit, the Adams County Sheriff's Office received a tip from a confidential informant that Joseph Foreman, better known as Afroman, was not only trafficking large amounts of marijuana, but he also "has a basement, referred to as 'the dungeon' in which he…keeps women locked in, forcing them to urinate and defecate in a bucket as punishment for upsetting or disobeying him."

Body camera footage of the raid shows the deputies—after the initial excitement of busting down the front door—ambling through Afroman's house, rifling through his clothes and CDs, and trying to find false walls and secret rooms.

But the hourslong search turned up no evidence to corroborate the claim of a basement dungeon. Part of the problem may have been that, as Afroman's record label told Vice, the house did not have a basement.

There was no big stash of weed either. According to search warrant documents, deputies recovered a glass jar containing "green leafy vegetation" (shake, according to deputies on the body camera footage), THC wax, and several pipes.

The deputies also seized more than $5,000 in cash, which they were ultimately forced to return. (The returned amount was $400 short, which an investigation later determined was due to a counting error by deputies.)

Reason has extensively written about how police departments use unreliable confidential informants and unverified tips to launch violent, unconstitutional raids.

In a statement to Reason on Afroman's behalf, Adam "Dot" Muniz, the director of operations for Music Access Inc., Afroman's distributor, says the search warrant's allegations are "entirely false. If there was any indication they were true, he would have been arrested during the unlawful police raid."

Afroman has yet to be charged with any crime. He subsequently used surveillance footage of the raid and cellphone video taken by his wife to lampoon the ACSO deputies. He released two music videos for songs mocking the cops, "Lemon Pound Cake" and "Will You Help Me Repair My Door." He also sold merchandise with images of the deputies and used the footage to promote his products and tours.

The mockery offended the deputies so much that seven of them filed a lawsuit against Afroman in March. The deputies argue Afroman used their personas for commercial purposes without permission, causing them to suffer "embarrassment, ridicule, emotional distress, humiliation, and loss of reputation."

The lawsuit also named Muniz's company. Muniz called the suit a "desperate cry" and said it originally misstated his company's name.

The Ohio chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union filed an amicus brief in support of Afroman's motion to dismiss the suit, arguing it's a blatant example of what's known as a strategic lawsuit against public participation (SLAPP).

"There is nothing the First Amendment guards more jealously than criticism of public officials on a matter of public concern, regardless of whether the criticism is harsh, or vulgar, or presented in a series of catchy music videos," David Carey, deputy legal director of the ACLU of Ohio, says. "The fact that Afroman may profit from his work does nothing to alter the First Amendment's protection, any more than a newspaper loses its protection by being sold. And the idea that public law enforcement officers have a protectable right to personal privacy while conducting a search of someone's home is nothing short of absurd—there are few scenarios that present less of a privacy interest than that."

One of Afroman's lawyers has previously said he intends to countersue.

Show Comments (53)