Newly Released Government Records Reveal Horrible Neglect of Terminally Ill Woman in Federal Prison

The records confirm medical neglect in a federal women's prison that Reason first reported on in 2020.

A woman who died in federal prison suffered in pain for eight months while waiting for a routine CT scan, records released to Reason show.

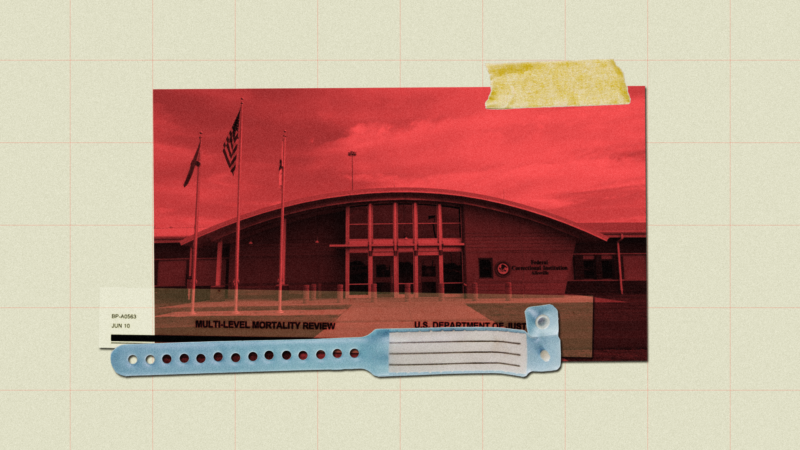

Doris Nelson was one of three inmates identified by a 2020 Reason investigation who have died since 2018 from alleged medical neglect at Federal Correctional Institution (FCI) Aliceville, a federal women's prison in Alabama. Reason reported on allegations of disastrous delays in medical care at Aliceville; desperate letters, lawsuits, and numerous interviews with current and formerly incarcerated women inside the prison described months-long waits for doctor appointments and routine procedures, retaliation from staff, and terrible pain and fear.

Reason filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request in 2020 for post-mortality reviews of all inmate deaths at Aliceville. Three years later, the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) finally released some of those reports. The Eighth Amendment is supposed to protect incarcerated people from medical neglect and cruelty, but a multi-level mortality review performed by the BOP shows that staff ignored Nelson's pleas for help for months while she lost the ability to walk. Staff advised her to take Motrin for excruciating pain and delayed and denied a CT scan that would have revealed the source of her torment: bone cancer.

Nelson was sentenced to nine years in federal prison for fraud in 2014. Her sentencing documents show a federal judge recommended to the BOP that she serve her sentence at a federal prison in Dublin, California, due to health issues. Instead, she ended up in Aliceville.

According to the records released to Reason, Nelson went to the prison's medical office on October 16, 2018, complaining of intense left hip pain.

She returned in January 2019, still complaining of severe hip pain. This time, x-rays were taken, which appeared to reveal a hip fracture. A follow-up CT scan was ordered, but months passed without further help for Nelson.

In April 2019, Nelson returned to sick call, "reporting worsening pain," but was advised to continue using over-the-counter painkillers like Motrin.

Her official health narrative within the mortality review notes that "the CT scan was deferred by URC," the prison's Utilization Review Committee. The URC approves or denies requests for outside medical treatment. The BOP attempted to redact this sentence from the records released to Reason, but an identical paragraph elsewhere in those same records was left unredacted.

In May, Nelson was seen by an orthopedist, who suggested a CT scan. But by June 1, 2019, when she returned to sick call "with severe pain, tearful and not able to bear weight," she had still not received that scan. The next day, Nelson fell out of bed. "She reported her leg would not hold her weight," the report notes.

By this point, Nelson had largely lost the ability to walk.

"She taught classes with me," Lorri Jackson-Brown, formerly incarcerated at Aliceville, told Reason in 2020. "Very nice lady, I loved Mrs. Nelson. One day I just happened to look up, and she's in a wheelchair."

Jackson-Brown says Nelson told her she felt flushed and couldn't walk: "She said, 'I stay in pain and medical's not doing anything for me. They won't do anything. I don't know what's going on with me."

Groups like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) say these kinds of delays, though unfortunately common in prisons and jails, violate the Eighth Amendment.

"Part of the constitutional right to healthcare that incarcerated people have is the fact that it needs to be timely," says Corene Kendrick, the deputy director of the ACLU's national prison project. "And that includes timely access to specialty care."

However, Kendrick says that many of the contractors who provide healthcare services in prisons and jails are paid flat per diem rates, incentivizing them to cut corners and keep patient costs as low as possible.

"A very common practice that we've seen by these companies operating in jails and prisons across the country is that they'll deny the initial request for specialty care and make the provider repeatedly request the same thing over and over," she says.

On June 13, 2019, Nelson fell again. This time, a medical emergency was called. "Her new pain was described as sharp straight down on her tailbone with pain now to left groin and hip area and lower back," the narrative says. "She was hyperventilating the entire time." Nelson was taken to the emergency room, and the long-awaited CT scan on her back and hip area was finally performed, revealing a "bony lesion… suggestive of metastatic disease."

Nelson was given a dose of morphine and sent back to Aliceville, with plans to return the next day to see an oncologist.

The next day, Nelson, 60, was in a prison transport van on the way to a local hospital when she slumped over, unresponsive. Staff and EMTs attempted to revive her with CPR, but she was declared dead at the hospital.

"I told her to meet me at the library on a Saturday," Jackson remembered. "Two days later she was dead."

"There was an ongoing struggle to get her diagnostic treatments," an attorney for Nelson's family told the Spokane, Washington, newspaper Spokesman-Review after her death. "She was in terrible pain and when I know more, I'll advise the family."

In the reports released to Reason, the BOP redacted all sections that would identify shortfalls or lapses in care regarding Nelson's death. Reason is currently litigating a FOIA lawsuit to challenge those and similar redactions in records concerning another federal women's prison.

Cases of medical neglect like Nelson's are far from unusual. For example, last year Reason reported how the BOP allowed a man's highly treatable colon cancer to progress until he was terminally ill, all while insisting in court that there was no evidence he had cancer and that he was receiving appropriate, timely care. A federal judge wrote that the BOP should be "deeply ashamed" of its actions, which were "inconsistent with the moral values of a civilized society and unworthy of the Department of Justice of the United States of America."

The Bureau of Prisons (BOP) has been under bipartisan pressure to clean up its act as more embarrassing stories of violence, neglect, and sexual misconduct have emerged. Earlier this month, bipartisan legislation was reintroduced in both the House and Senate that would create an independent ombudsman to act as a BOP watchdog.

The U.S. Sentencing Commission, which issues guidelines on federal sentencing laws and policies, proposes expanding the "compassionate release" policy to include incarcerated people suffering from medical neglect.

"The BOP has failed so miserably and for so long as providing adequate care that the Sentencing Commission is stepping in," says Kevin Ring, president of the criminal justice advocacy group FAMM. "They are proposing to expand the grounds for compassionate release to include people who are being neglected and put at risk of serious deterioration or death. It's sad that BOP needs to be told not to kill people through neglect, but here we are."

The Bureau of Prisons did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

Show Comments (15)