Electric Car Prices Are Falling, With or Without Tax Credits

The Inflation Reduction Act imposes byzantine requirements to qualify for the credits. Some automakers are simply ignoring them and finding other ways to lower prices.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 established tax credits of up to $7,500 to buy an electric vehicle (E.V.). Lawmakers wanted the credits to lower the cars' prices, but market forces will probably do a better job of that.

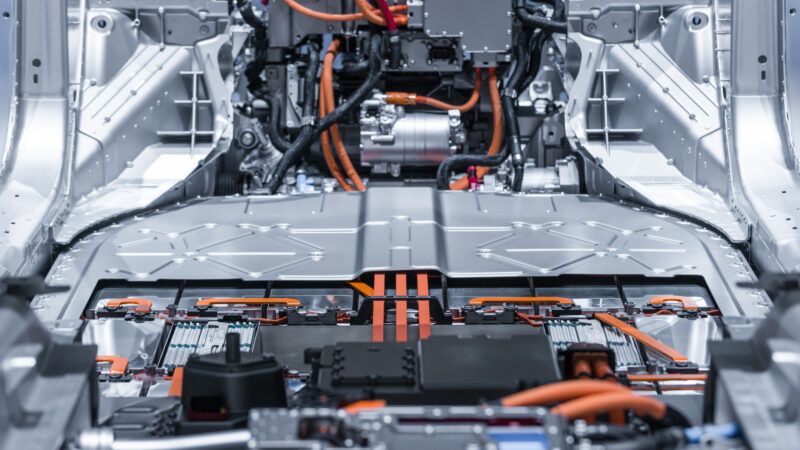

On March 31, the Treasury Department issued its rules for the E.V. credits, set to take effect April 18. To qualify, a vehicle's "final assembly" must occur in North America and a certain percentage of the battery's parts must be sourced from either the U.S. or a country with which the U.S. has a trade agreement. In 2023, 40 percent of all the minerals used to make an E.V.'s battery—chiefly graphite, lithium, cobalt, manganese, and nickel—must be sourced from the U.S. or a trade-agreement partner; that number goes up each year until 2026, when it hits 80 percent. And 50 percent of the battery's components, such as battery cells and electrodes, must also be sourced from the U.S. or a trade-agreement partner, a number that gradually increases to 100 percent in 2029.

The law was clearly drafted with China in mind. Indeed, starting in 2024, no qualifying vehicles may contain any components sourced from a "foreign entity of concern." The new rules state, "The Treasury Department and the IRS recognize that more secure and resilient supply chains are essential for our national security, our economic security, and our technological leadership."

Compliance will be easier said than done. China accounts for about 80 percent of the global refining capacity for raw battery materials, and it is the world's largest producer of graphite.

Though fewer and fewer automakers will be able to qualify for credits as the percentage requirements go up, some are trying. In January, General Motors (G.M.) agreed to invest $650 million for a stake in a Nevada mine containing the nation's largest (and the world's third largest) known source of lithium. Tesla reconfigured its product so that half of the cars it sold in the first quarter of 2022 contained no nickel or cobalt in the batteries.

Meanwhile, Ford Motor Co. is going in the opposite direction. In March, the company announced that it was investing in an Indonesian nickel mine alongside two other companies, including a leading Chinese refining firm. Indonesia has the largest nickel mines on earth, and the laws there require companies who want the nickel to extract it themselves. While this would almost certainly preclude the company from qualifying for incentives, Lisa Drake, Ford's vice president for E.V. industrialization, said the deal "gives Ford direct control to source the nickel we need—in one of the industry's lowest-cost ways."

All of these developments have implications reaching far beyond one law's byzantine rules. Finding domestic sources of component materials, or developing ways of manufacturing the same product with fewer rare materials, makes companies more competitive with one another. As The New York Times noted in February, "arguably the most powerful force driving down prices is not the commodity markets or Washington."

According to the Times, companies like Ford and G.M. are finding less expensive ways to manufacture their products, such as lowering gross vehicle weights by eliminating redundant systems. Because they use fewer parts than cars with internal combustion engines, E.V.s are also easier to produce at scale. And suppliers are developing newer and more efficient methods of building batteries and fuel cells, lowering costs without sacrificing performance.

Last year, G.M. lowered the price of the Chevrolet Bolt by nearly $6,000. Tesla has lowered its prices fives times since January in order to spur demand. Ford responded by dropping the price of its all-electric Mustang, the best-selling E.V. not made by Tesla.

While a tax credit may seem appealing, it's still a distortion of the market: After lowering prices on the Bolt last year, G.M. raised the price in January just days after it temporarily regained tax-credit eligibility. It is automakers losing access to the credits that are finding more permanent ways to make their products more affordable.

Show Comments (93)