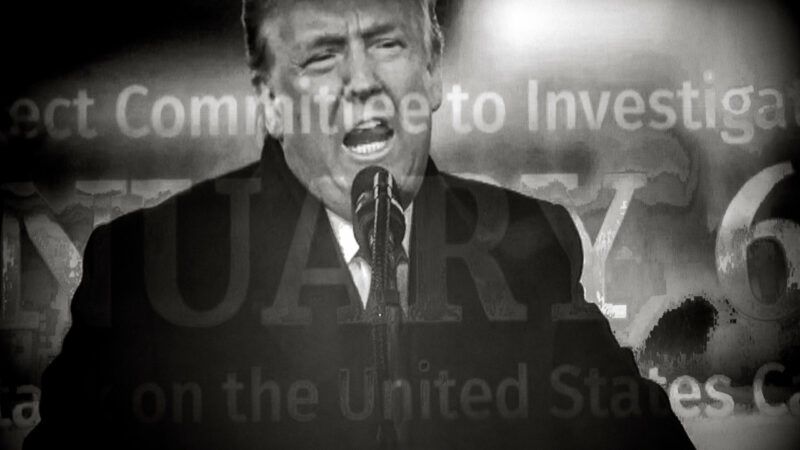

The January 6 Committee's Suggested Charges Against Trump May Be Hard To Prove

The leading possibilities include knowledge and intent elements that have to be established beyond a reasonable doubt.

The select congressional committee investigating the January 6, 2021, riot at the U.S. Capitol on Monday recommended that the Justice Department consider half a dozen criminal charges against Donald Trump based on his efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election. While those criminal referrals are not binding, they suggest some of the challenges that prosecutors would face if they decided there is enough evidence to charge the former president.

Four of the potential crimes include mens rea requirements that may be difficult to satisfy, especially since the prosecution would have to prove those elements beyond a reasonable doubt. The other two possibilities involve conspiracies that the committee was unable to substantiate, although it suggests that the Justice Department might have more success.

The committee argues that Trump violated 18 USC 1512(c) when he summoned his supporters to a "Stop the Steal" rally in Washington, D.C., on the day that Congress was meeting to certify Joe Biden's victory, then riled them up with a fiery speech and pointed them toward the Capitol. The statute makes it a felony, punishable by up to 20 years in prison, to "corruptly" obstruct an "official proceeding."

That law has figured prominently in the criminal cases against Trump supporters who disrupted the electoral vote count by trespassing on Capitol grounds, illegally entering and vandalizing the building, and/or assaulting police officers. But to make the charge stick against Trump, prosecutors would have to prove that he acted "corruptly," which federal appeals courts have defined as acting "with an improper purpose and to engage in conduct knowingly and dishonestly with the specific intent to subvert, impede or obstruct" an official proceeding.

According to an analysis by the Rollins and Chan Law Firm, which represents criminal defendants in D.C. and Maryland, that element is "easy to prove" when a defendant "broke into the Capitol, broke windows, destroyed property, went into offices, or went into the chamber." But it is harder to prove when a defendant, like Trump, is accused of playing an indirect role in the riot.

Trump, who urged the audience at his rally to "peacefully and patriotically make your voices heard today" by "marching over to the Capitol building," insists that he did not intend to cause a riot. And while his "fight like hell" rhetoric in that context was undeniably reckless, it is plausible, given what we know about Trump, that he was so narrowly focused on promoting his own cause that he did not consider the likely impact of his words. Heedless self-absorption is not the same as acting "knowingly and dishonestly with the specific intent" to interrupt the ratification of the election results.

The committee's allegations go beyond what Trump did at the rally. "President Trump was attempting to prevent or delay the counting of lawful certified Electoral College votes from multiple States," it says. "President Trump was directly and personally involved in this effort, personally pressuring Vice President Pence relentlessly as the Joint Session on January 6th approached." Trump wanted Pence to unilaterally reject electoral votes for Biden from several states, which the vice president refused to do after concluding that he had no such authority.

As evidence that Trump acted "corruptly" when he pressured Pence, the committee notes that Pence, his chief counsel, and others "repeatedly told the President that the Vice President had no unilateral authority to prevent certification of the election." It cites a January 6 email exchange in which Trump legal adviser John Eastman "admitted that President Trump had been 'advised' that Vice President Pence could not lawfully refuse to count votes under the Electoral Count Act." Eastman—who was instrumental in formulating that plan, which he argued was constitutional even though it was contrary to statute—added that "once he gets something in his head, it's hard to get him to change course."

That assessment is ambiguous: Did Trump proceed with his cockamamie scheme even though he knew it was illegal, or did he reject advice to that effect because it was inconvenient? The latter would be completely in character.

During the battle over the committee's access to Eastman's emails, the panel notes, U.S. District Judge David Carter concluded that Trump "likely violated" 18 USC 1512(c). Trump "likely knew the electoral count plan had no factual justification," he wrote. "The plan not only lacked factual basis but also legal justification." Because Trump "likely knew that the plan to disrupt the electoral count was wrongful," Carter said, "his mindset exceeds the threshold for acting 'corruptly.'"

Maybe, but that assumes Trump knew his wild fraud allegations were false, a point that remains unclear to this day, and understood the law well enough to deliberately defy it. Both of those propositions are debatable, and the "preponderance of the evidence" standard that Carter applied is much less demanding than the proof required for a criminal conviction.

The committee's argument that Trump violated 18 USC 371 raises similar issues. That statute makes it a felony, punishable by up to five years in prison, to conspire with at least one other person to "defraud the United States," provided that scheme includes "any act to effect the object of the conspiracy." As relevant here, the prosecution has to prove that the conspiracy involved "interference or obstruction of a lawful governmental function 'by deceit, craft or treachery or at least by means that are dishonest.'"

If you assume that Trump never sincerely believed the election was stolen, his efforts to change the outcome, including his "alternate electors" scheme, were plainly dishonest. But if you think it is plausible that Trump drank his own Kool-Aid, the picture is murkier. Maybe he was pressing claims he thought were legitimate, despite all the contrary evidence.

"President Trump repeatedly lied about the election, after he had been told by his advisors that there was no evidence of fraud sufficient to change the results of the election," the committee says. But a lie requires deliberate deceit, and a jury might reasonably conclude that Trump's narcissism blinded him to the truth. More to the point, it might conclude there is reasonable doubt as to whether Trump knew his self-serving fantasy was nothing more than that. Judge Carter, who thought it more likely than not that Trump and Eastman had conspired to defraud the United States, did not really grapple with the possibility that Trump deceived himself.

The committee also alleges that Trump violated 18 USC 1001, which covers "any materially false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or representation" to the government. The panel says Trump committed that felony, which is punishable by up to five years in prison, when he encouraged others to submit "slates of fake electors" to Congress and the National Archives. To convict Trump of that crime, the prosecution would have to show that he acted "knowingly and willfully," meaning he understood that the slates were fraudulent.

As evidence of that, the committee notes that Trump "relied on the existence of those fake electors as a basis for asserting that the Vice President could reject or delay certification of the Biden electors." But it is still possible that Trump thought both of those maneuvers were legitimate, based on the advice of the lawyers he favored because they said what he wanted to hear.

The committee also suggests that Trump's January 6 speech amounted to incitement of insurrection, a felony punishable by up to 10 years in prison under 18 USC 2383. It argues that his comments were not protected by the First Amendment because they were likely to inspire violence. But the Supreme Court has held that even someone who explicitly advocates criminal behavior (which Trump did not do) is constitutionally protected from prosecution unless his speech is not only "likely" to incite "imminent lawless action" but also "directed" at that outcome. Again, that makes Trump's intent crucial: Did he deliberately encourage violence, or did he blithely disregard that danger?

Finally, the committee suggests that Trump could be guilty of seditious conspiracy, a felony punishable by up to 20 years in prison. As relevant here, that statute, 18 USC 2384, applies to anyone who conspires to "prevent, hinder, or delay the execution of" a federal law (in this case, the Electoral Count Act) "by force." Members of the Oath Keepers militia who participated in the Capitol riot have been convicted of that crime, and members of the Proud Boys face similar charges. The committee concedes that it was unable to substantiate any connection between Trump and those plots but hopes the Justice Department can do better.

The committee also mentions 18 USC 372, which covers conspiracies "to prevent, by force, intimidation, or threat, any person from accepting or holding any office, trust, or place of confidence under the United States, or from discharging any duties thereof, or to induce by like means any officer of the United States to leave the place, where his duties as an officer are required to be performed, or to injure him in the discharge of his official duties." That felony, which is punishable by up to six years in prison, likewise requires evidence that the committee thinks the Justice Department might be able to uncover, assuming it exists.