We Have a Printing Paper Problem

A new supply chain parable for our times

I, Magazine, simple though I appear to be, merit your wonder and awe. I am seemingly so simple, yet not a single person on the face of this Earth knows how to make me.

Fans of the great Leonard Read will recognize (and hopefully forgive) the bastardization of his lovely market parable, "I, Pencil." As Milton Friedman wrote of this brief, powerful essay by the founder of the Foundation for Economic Education: "I know of no other piece of literature that so succinctly, persuasively, and effectively illustrates the meaning of both Adam Smith's invisible hand—the possibility of cooperation without coercion—and Friedrich Hayek's emphasis on the importance of dispersed knowledge and the role of the price system in communicating information."

While my affection for Read's essay remains undimmed, my faith in the mechanisms it describes has been tested over the last several months. I'm not alone in this: Consumers around the world are more aware than ever before of the workings of their supply chains—and of what happens to prices and availability when those lines are strained. From the toilet paper shortage that kicked off the pandemic to the semiconductor crunch of 2022, it's been an education.

Until recently, I had only the vaguest grasp of the specific complex market that enabled the physical version of Reason magazine to come into being. This is as it should be; my ignorance was one of the great gifts of functioning markets.

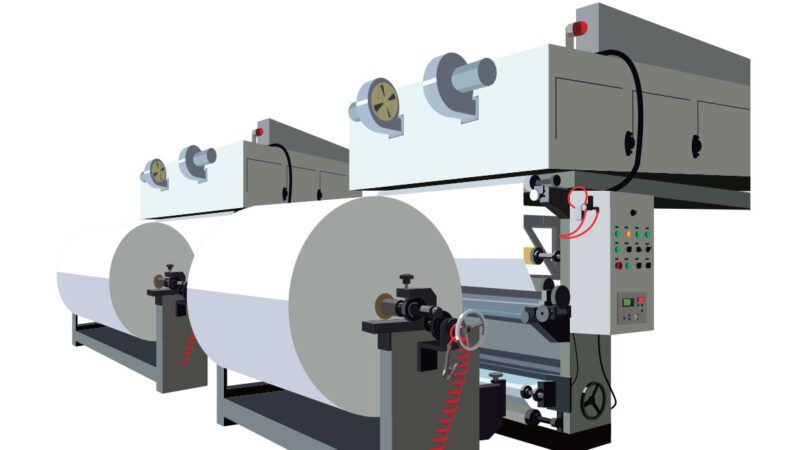

For the last 17 years, Reason has bought its paper in enormous lots from UPM-Kymmene Oyj, a Helsinki-based company. A typical order is 20 metric tons. Shipping containers of UPM paper float from Kotka-Hamina or other ports to Baltimore on the slowest of slow boats, where they are unloaded onto trucks and taken to Little Rock, Arkansas. There, Reason is printed by Democrat Printing & Lithographing Co., a family firm founded in 1871, alongside dozens of other publications. Each issue is then delivered to readers by the planes, trains, trucks, and weary feet of the U.S. Postal Service. All of this is coordinated by Reason's publisher, Mike Alissi.

Several months back, though, prices started to rise at every step of this process. And prices, as Hayek taught us, contain information. They were warning, it turns out, of a dire turn of events.

The story of what went wrong with the paper supply begins before the pandemic. As many publications—periodicals and books, as well as business mailings, election materials, and more—shifted to digital, paper mills found themselves with too much capacity and too much supply. Prices were low, and paper was easy to obtain on short notice. So available, in fact, that most customers didn't bother to keep large amounts of inventory on hand.

This situation was not terribly favorable to paper producers. So they adapted. They took some plants offline, and they retooled others to produce the kind of paper that is useful in packaging—a growing segment of the market as e-commerce boomed.

Then the pandemic hit, and the paper industry suffered as all industries suffered, from lockdowns, labor shortages, and, eventually, a lack of raw materials as global shipping got weird.

The price of wood pulp spiked, for instance. China overtook the U.S. in 2009 as the top producer and consumer of paper products, and an environmental initiative in China that shut down 279 pulp and paper mills may have been partially responsible for an increase in the price of wood pulp—it rose from about $750 per metric ton in 2020 to almost $1,200 per metric ton in 2021.

Things were already tight when UPM workers went on strike. The relationship between employers and workers in Finland tends to be pretty peaceable, so at first this didn't seem like a huge cause for alarm, even given that the system was already under some stress. But the strike, which began on January 1, 2022, stretched on and on.

Since Finnish labor politics are rarely covered in detail in the English-language press, our trusty paper broker Cliff Roth resorted to getting hot gossip from a pal in Finland. The news was not good. "As you'll read," Roth wrote atop an April Google-translated dispatch, "the 'Printing Paper' talks have been temporarily suspended by the Arbitrator, while talks in other product areas continue, because the 'Printing Paper' parties are so far apart."

Finally, on April 22, the parties came to a resolution, and the strike ended. But, as described above, paper doesn't move quickly. Even without an ongoing pandemic, it would take a while to get the plants back online, the shippers back under contract, and more.

"I started in the paper business in 1969," says Roth, who has supplied Reason with paper for decades. "Over that period, there have been tight markets. There have been markets where the buyers were scrambling and the sellers were more or less on the top of the hill. That cycles every four or five years. But I have never seen anything like this in all those years. It has just been absolutely incredible."

As we scrounge around to find paper in tough times, I'm reminded of another gal who faced some similar challenges.

Ayn Rand, not famed for her brevity, struggled to find a publisher for The Fountainhead and then immediately ran face-first into wartime paper shortages. She fought cuts to her copy fiercely, and when the book was finally printed in 1943, it was a relatively small run of 7,500 copies. Despite brutal reviews, demand grew until her publisher had to cut a deal with another printer, Blakiston—"a small press with a large paper quota," according to Rand biographer Jennifer Burns.

Rand was the master of the snippy business letter. I recommend browsing the Ayn Rand Institute's archives if you're ever at a loss for words in your own workaday correspondence. In one of many hectoring missives, she wrote to her publisher: "War conditions of the printing industry do not relieve you of the contractual obligation to keep my book in print in step with the demand. Since we know that everything is done slower now, we must make our calculations accordingly."

And so must Reason. It's fitting that this is our summer double issue and a special book issue, revived from a past era when editions of the magazine devoted to books were more common. Book sales were at an all-time high during the pandemic, with folks setting aside once-popular self-help books to read first about baking and then social justice, before finally giving in to the temptation of adult fiction. That uptick in reading is a double-edged sword for us this month, editorially. With so many books to cover, we needed every page of this double issue, even as those pages have grown both expensive and scarce. The 2022 books issue focuses on banned books, with a rather broad interpretation of the forces that can keep books out of readers' hands, including factors you might not think of as traditional state censorship.

The scramble to find paper has been rough, but it is still infinitely preferable to any centrally managed or allocated process. For one thing, you can be rather sure that a magazine that questions the conduct of economic regulators at every turn would find itself at the end of the line for paper even in the best of times.

In the short run, Reason is going to show up at your house on some unusual paper. Our usual stuff won't be available for months. We've already been subbing in some slightly different papers, but this one should be noticeably so: It's matte, instead of our usual silk. According to Roth, it's also "toothier." It's also a little more likely to crease and a lot more expensive to ship, since it's heavier.

We hope you'll bear with us, because we're not ready to give up on dead trees yet. As Read well knew, there's something miraculous about holding the product of so many people's labor and ideas in your hands—a tangible representation of the marvelously free, interconnected world in which we live.

"The lesson I have to teach is this," declared Read's personified pencil. "Leave all creative energies uninhibited. Merely organize society to act in harmony with this lesson. Let society's legal apparatus remove all obstacles the best it can. Permit these creative know-hows freely to flow. Have faith that free men and women will respond to the Invisible Hand. This faith will be confirmed."

I, Magazine, seemingly simple though I am, offer the miracle of my creation as testimony that this is a practical faith.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "We Have a Printing Paper Problem."

Show Comments (121)