The Defense Production Act Has Become a License for Central Planning

If home insulation is a "critical technology item essential to the national defense," then what isn't?

President Donald Trump was never one with high regard for the limits of his executive authority. Yet when people first floated the idea of using the 1950 Defense Production Act (DPA) to force private sector businesses to prioritize orders from the federal government for masks, ventilators, and other gear, the idea gave Trump a moment's pause.

"We're a country not based on nationalizing our business," Trump said at a March 2020 press conference. "Call a person over in Venezuela; ask them how did nationalization of their businesses work out. Not too well."

It didn't last, and Trump did eventually sign a declaration invoking the DPA. But if you think it was a stretch to respond to a pandemic with a law designed to ensure the military can access supplies during wartime, wait 'til you find out the ways Trump's successor has been using it.

The production of vaccines? Check.

Rare minerals needed for electric car batteries? Check.

Baby formula? Check—despite the role that his own government played in creating that shortage in the first place.

Solar panels, heat pumps, and…home insulation? Check, check, and check.

How, exactly, is insulation related at all to national security? According to the White House, it's because "insulation is an industrial resource, material, or critical technology item essential to the national defense." By that standard, what product isn't essential to national defense?

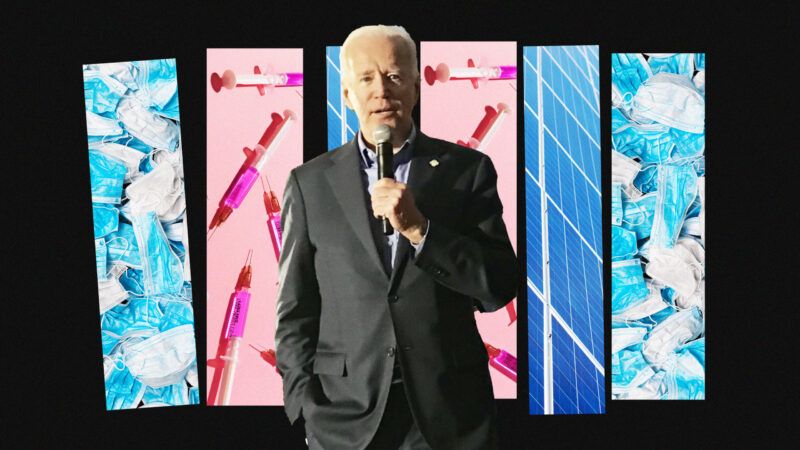

The Defense Production Act has become President Joe Biden's go-to "solution" to any market that isn't operating quite how he'd like. It's the back door to central planning: just declare any product to be of a vital national security interest. Who's going to stop you? Certainly not Congress, and so far not the courts either.

The justifications for invoking the DPA are "just getting thinner and thinner the more it gets used," argues Philip Rossetti, a senior fellow at the R Street Institute. Rossetti tells Reason that the DPA isn't being used to increase production overall, but rather to reorganize the market under the White House's direction.

"And that's going to come at a cost to wherever you're taking those resources from," he says, because "government doesn't produce; government simply takes from one area and puts it towards another."

Trump was not the first president to call up on the DPA for something other than a wartime emergency. President Bill Clinton invoked the law in 2000 to force providers to keep selling natural gas to California's largest electricity provider despite the utility's bankruptcy. In 2011, President Barack Obama used the law to compel telecommunications companies to disclose foreign-made components within their networks—an early battle in an ongoing conflict between the U.S. government and Huawei, the major Chinese manufacturer of high-end telecom gear.

Like other examples of executive excess, the Defense Production Act has evolved over time as presidents from both parties stretch the boundaries of their authority. While Trump was reluctant to use the DPA, he eagerly stretched the definition of "national security" in order to unilaterally impose tariffs under a different Cold War-era law. And now, just as Obama built on President George W. Bush's war powers when he bombed Libya, Biden has inherited both Trump's use of the DPA and his willingness to make every economic issue a national security one—and he's put the two together.

While the DPA was passed in 1950, its roots go back to World War I, when President Woodrow Wilson created the National War Labor Board and War Industries Board to oversee the production of wartime supplies. When the U.S. entered World War II, Congress passed the War Powers Act of 1941 to codify many of those same economic powers. But in both cases, the powers expired when the wars ended.

Not so with the DPA, which was passed in the early days of the Korean War at the request of President Harry Truman. To this day, the law allows the federal government to prioritize contracts of goods deemed to be vital to national security, to expand productive capacity with loans and grants, and to make special financing agreements with the private sector.

It could be worse. Four other parts of the law have gone extinct because Congress has not seen fit to reauthorize them, including provisions that allowed presidents to seize private property, set wages and prices, forcibly settle labor disputes, and exercise control over consumer credit access. Imagine a president invoking the DPA to set the price of gasoline or to impose the labor order he prefers on Amazon warehouses.

Even without those elements, the expansive use of the DPA during Biden's term raise questions about the law's economic efficacy and legal limits. "Clarity about what the law does and does not allow is yet another thing in short supply," The Economist notes.

A few politicians have complained about the way the law is being used, as when Sen. Pat Toomey (R–Pa.) tweeted that "After gas, solar panels, and baby food, Congress should rename the Defense Production Act the Domestic Politics Act."

But the overwhelming bulk of the pressure is coming from the other direction. Dozens of members of Congress and hundreds of mayors urged Trump to invoke the DPA in response to COVID-19. When the president waivered, publications like Vox waved away Trump's concerns (after years of objecting to Trump's many other expansive uses of executive power). The clamor for Biden to declare the production of heat pumps and solar panels matters of national security hasn't been as strong, but it's clear that industry lobbies have added the DPA to their bag of cronyist tricks.

The underappreciated risk is a potential moral hazard, says Rossetti. The DPA makes political connections more valuable than success in the marketplace, making the economy less stable economy and, thus, paving the way for more calls for emergency actions.

"The way you grow the economy is by productivity improvements and letting the market identify what consumers actually view as valuable activities," Rossetti says. "This is exactly an opposite approach of that philosophy. It's a central-planning mindset."

Show Comments (27)