There Is a Reason Why Roe v. Wade's Defenders Focus on Its Results Rather Than Its Logic

The abortion precedent has faced withering criticism, including damning appraisals by pro-choice legal scholars, for half a century.

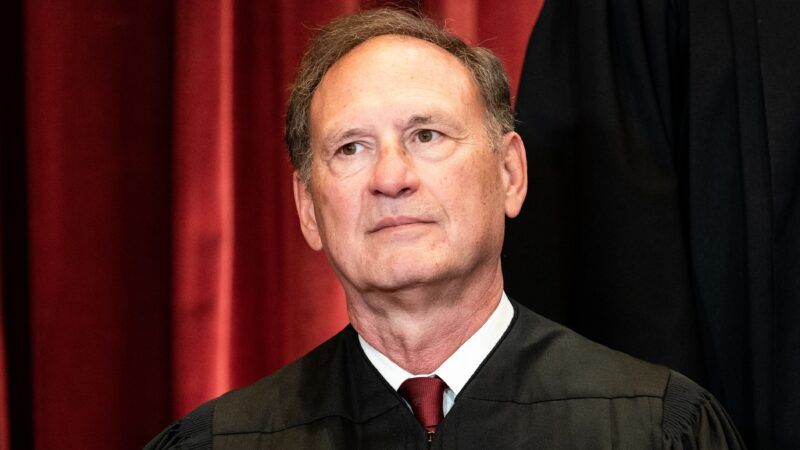

Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, a pro-choice Democrat, says she was "devastated" by the draft majority opinion in which Justice Samuel Alito explains why he believes the Supreme Court cannot let Roe v. Wade stand. "It was shocking to see, laid out in cold legalese, the blatant ideological reasoning gutting the constitutional right to abortion," Whitmer writes in The New York Times.

The implication is that Alito, because he opposes abortion, was determined to overturn the 1973 decision establishing that right, regardless of the legal contortions it required. But as Alito emphasizes, Roe has faced withering criticism, including damning appraisals by pro-choice legal scholars, for half a century. Roe's supporters tend to ignore that fact, instead emphasizing the practical impact of freeing states to set their own abortion policies. While Whitmer accuses Alito of motivated reasoning, that charge better fits Roe author Harry Blackmun and the decision's contemporary defenders.

The source of the right identified in Roe was rather mysterious. Although the Constitution does not mention abortion, Blackmun said it was covered by the "right to privacy," which likewise is not mentioned in the Constitution but in his view could be inferred from other provisions.

The seven justices in the majority did not seem very concerned about precisely which provisions those were. But they were sure "this right of privacy, whether it be founded in the Fourteenth Amendment's concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, as we feel it is, or, as the District Court determined, in the Ninth Amendment's reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a woman's decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy." The message, Alito says, "seemed to be that the abortion right could be found somewhere in the Constitution and that specifying its exact location was not of paramount importance."

Unfazed by that uncertainty, the justices went further, laying out a detailed list of purportedly constitutional restrictions on state abortion regulations. "For the stage prior to approximately the end of the first trimester," Blackmun said, "the abortion decision and its effectuation must be left to the medical judgment of the pregnant woman's attending physician." After that, "the State, in promoting its interest in the health of the mother, may, if it chooses, regulate the abortion procedure in ways that are reasonably related to maternal health." Finally, "for the stage subsequent to viability, the State in promoting its interest in the potentiality of human life may, if it chooses, regulate, and even proscribe, abortion except where it is necessary, in appropriate medical judgment, for the preservation of the life or health of the mother."

Those rules, which were somehow inferred from a "right to privacy" of unclear provenance and breadth, effectively invalidated every abortion law in the country. The result, Roe's critics say, was decades of acrimony provoked by the lawless nationalization of abortion policy. Even supporters of abortion rights have argued that much of that anger could have been avoided if the Court had treaded more carefully.

Prior to joining the Court, Ruth Bader Ginsburg criticized Roe's reasoning and its scope. Ginsburg, who argued that abortion bans amounted to unconstitutional sex discrimination, thought the 14th Amendment's guarantee of equal protection would have provided a firmer foundation for the right announced in Roe. She also faulted the Court for deciding more than was required to resolve the case, which involved a Texas law that banned abortion except when it was deemed necessary to save the mother's life.

"Doctrinal limbs too swiftly shaped, experience teaches, may prove unstable," Ginsburg, then an appeals court judge, said in a 1992 lecture. "Suppose the Court had stopped [after] rightly declaring unconstitutional the most extreme brand of law in the nation, and had not gone on, as the Court did in Roe, to fashion a regime blanketing the subject, a set of rules that displaced virtually every state law then in force. Would there have been the 20-year controversy we have witnessed, reflected most recently in the Supreme Court's splintered decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey? A less encompassing Roe, one that merely struck down the extreme Texas law and went no further on that day…might have served to reduce rather than to fuel controversy." Instead, she said, the Court had "prolonged divisiveness," "deferred stable settlement of the issue," and "halted a political process that was moving in a reform direction."

Ginsburg's criticism, which Alito mentions in his draft opinion, was mild compared to the comments of other observers who, like her, opposed tight restrictions on abortion. The Washington Examiner's Timothy P. Carney has collected some striking examples.

"What is frightening about Roe is that this super-protected right is not inferable from the language of the Constitution, the framers' thinking respecting the specific problem in issue, any general value derivable from the provisions they included, or the nation's governmental structure," Yale law professor John Hart Ely wrote in a 1973 Yale Law Journal article. "At times the inferences the Court has drawn from the values the Constitution marks for special protection have been controversial, even shaky, but never before has its sense of an obligation to draw one been so obviously lacking." In short, Ely said, Roe "is not constitutional law and gives almost no sense of an obligation to try to be."

Harvard law professor Lawrence Tribe offered a similar assessment around the same time. "One of the most curious things about Roe is that, behind its own verbal smokescreen, the substantive judgment on which it rests is nowhere to be found," Tribe wrote in the Harvard Law Review.

"As a matter of constitutional interpretation and judicial method, Roe borders on the indefensible," former Blackmun clerk Edward Lazarus wrote in 2002. "I say this as someone utterly committed to the right to choose, as someone who believes such a right has grounding elsewhere in the Constitution instead of where Roe placed it, and as someone who loved Roe's author like a grandfather." Lazarus argued that "a constitutional right to privacy broad enough to include abortion has no meaningful foundation in constitutional text, history, or precedent—at least, it does not if those sources are fairly described and reasonably faithfully followed."

Carney quotes similar comments from University of Pennsylvania law professor Kermit Roosevelt, Harvard law professors Alan Dershowitz and Cass Sunstein, and journalists such as William Saletan, Benjamin Wittes, Richard Cohen, Jeffrey Rosen, and Michael Kinsley. "Although I am pro-choice," Kinsley wrote in 2004, "I was taught in law school, and still believe, that Roe v. Wade is a muddle of bad reasoning and an authentic example of judicial overreaching."

All of these commentators managed to separate their policy preferences from their assessments of Roe's legal merits. And all of them were decidedly unimpressed by the latter.

Casey, the "splintered decision" to which Ginsburg referred in her 1992 lecture, did not improve matters much. The controlling opinion by Justices Sandra Day O'Connor, Anthony Kennedy, and David Souter ditched Roe's "rigid trimester framework" but retained its "central holding," which bars states from banning pre-viability abortions. Their rationale focused on the consequences of upsetting a longstanding precedent.

"For two decades of economic and social developments, people have organized intimate relationships and made choices that define their views of themselves and their places in society, in reliance on the availability of abortion in the event that contraception should fail," O'Connor et al. said. "The ability of women to participate equally in the economic and social life of the Nation has been facilitated by their ability to control their reproductive lives….A decision to overrule Roe's essential holding under the existing circumstances would address error, if error there was, at the cost of both profound and unnecessary damage to the Court's legitimacy, and to the Nation's commitment to the rule of law. It is therefore imperative to adhere to the essence of Roe's original decision."

That opinion not only declined to endorse Roe's reasoning; it conceded that the decision may have been erroneous. "Very little of Roe's reasoning was defended or preserved," Alito writes. "The Court abandoned any reliance on a privacy right and instead grounded the abortion right entirely on the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause. The Court did not reaffirm Roe's erroneous account of abortion history. In fact, none of the Justices in the majority said anything about the history of the abortion right. And as for precedent, the Court relied on essentially the same body of cases that Roe had cited. Thus, with respect to the standard grounds for constitutional decisionmaking—text, history, and precedent—Casey did not attempt to bolster Roe's reasoning."

Alito adds that Casey "made no real effort to remedy one of the greatest weaknesses in Roe's analysis—its much-criticized discussion of viability." Here is how Roe justified that controversial dividing line: "With respect to the State's important and legitimate interest in potential life, the 'compelling' point is at viability. This is so because the fetus then presumably has the capability of meaningful life outside the womb." As Ely observed, "the Court's defense seems to mistake a definition for a syllogism." Casey likewise simply declared that viability is the point where "the independent existence of a second life can in reason and fairness be the object of state protection that now overrides the rights of the woman."

Alito's analysis of the claim that the Due Process Clause protects a right to abortion starts with the premise that unenumerated rights protected by the 14th Amendment must be "deeply rooted in this Nation's history and tradition" and "implicit in the concept of ordered liberty." Given the long history of criminalizing abortion in the United States, he argues, it is clear that the right to abortion does not fall into that category. He also considers and rejects the equal protection approach that Ginsburg favored, although he does not directly address the argument that the 14th Amendment protects a right to "bodily integrity" broad enough to cover abortion.

Alito argues that Casey not only failed to "bolster Roe's reasoning" but also botched the question of whether overturning the decision was consistent with principles of stare decisis. That analysis, he says, placed "great weight on an intangible form of reliance with little if any basis in prior case law" while giving short shrift to Roe's constitutional infirmities.

Some critics of Roe disagree on that point. New York Times columnist Bret Stephens, for example, concedes that "Roe v. Wade was an ill-judged decision" that "arrogated to the least democratic branch of government the power to settle a question that would have been better decided by Congress or state legislatures." He adds that Roe "set off a culture war that polarized the country, radicalized its edges and made compromise more difficult"; "helped turn confirmation hearings for the Supreme Court into the unholy death matches they are now"; and "diminished the standing of the court by turning it into an ever-more political branch of government."

But Stephens argues that overturning Roe half a century later would be "a radical, not conservative, choice" because of the longstanding expectations it would upset, and he warns that such a reversal (like Roe itself) would damage the Court's reputation and undermine respect for the law. This is essentially the argument that swayed O'Connor et al. in Casey. But it starts by recognizing Roe's manifest flaws—something the decision's result-oriented defenders rarely do.

Show Comments (232)