SCOTUS Rules That California Violated the First Amendment by Routinely Demanding Donor Information From Advocacy Groups

Six justices agreed that the state's "dragnet for sensitive donor information" imposes "a widespread burden on donors' associational rights."

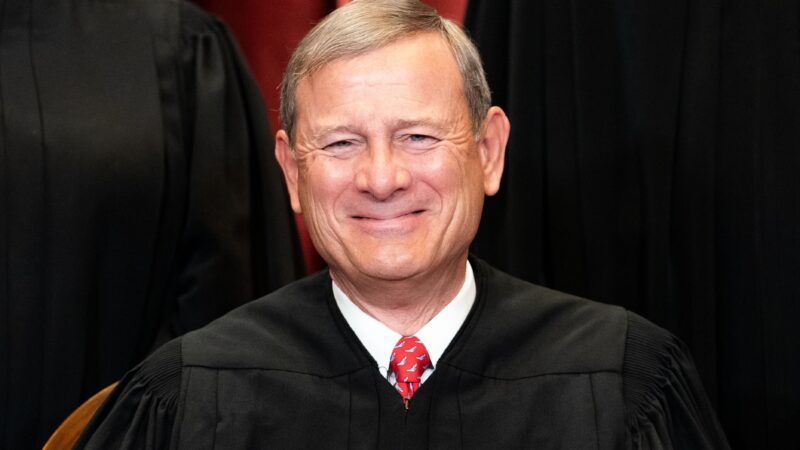

The Supreme Court today ruled that California violated the First Amendment by demanding that all charitable organizations operating in the state disclose information about their major donors. Given the potential chilling effect on freedom of association and the state's weak justification for demanding donor information, Chief Justice John Roberts says in the majority opinion, California's regulation fails to satisfy "exacting scrutiny," the standard that the Court has applied in other compelled disclosure cases.

The decision vindicates a principle that the Court recognized 63 years ago in NAACP v. Alabama, which involved that state's demand for the civil rights organization's membership lists. In that case, the Court noted that such requirements can pose a grave threat to freedom of association, exposing supporters of controversial organizations to the risk of harassment, threats, and violence. "Compelled disclosure of affiliation with groups engaged in advocacy may constitute as effective a restraint on freedom of association as [other] forms of governmental action," the justices observed in 1958.

Advocacy groups that objected to California's nosiness argued that it posed a similar danger, and the Court agreed. "The Attorney General's disclosure requirement imposes a widespread burden on donors' associational rights," Roberts writes in an opinion that was joined in most respects by five other justices. "And this burden cannot be justified on the ground that the regime is narrowly tailored to investigating charitable wrongdoing, or that the State's interest in administrative convenience is sufficiently important. We therefore hold that the up-front collection of [donor information] is facially unconstitutional, because it fails exacting scrutiny in 'a substantial number of its applications…judged in relation to [its] plainly legitimate sweep.'"

California has for many years officially required that nonprofit groups, as a condition of raising money in the state, submit both IRS Form 990, which includes information about a tax-exempt organization's mission, leadership, and finances, and Schedule B of Form 990, which lists the names and addresses of individuals who have donated more than $5,000 to the organization in a given tax year. But California did not begin enforcing the latter requirement in earnest until 2010.

The Americans for Prosperity Foundation and the Thomas More Law Center refused to comply, arguing that the disclosure requirement was inconsistent with the First Amendment. A federal judge agreed, but the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit reversed that decision and upheld the Schedule B requirement. The two groups, joined by a remarkably diverse array of nonprofit organizations spanning a wide range of interests and political viewpoints, asked the Supreme Court to overturn the 9th Circuit's decision.

Roberts' majority opinion says the 9th Circuit erred by failing to require that California's regulation be "narrowly tailored" to serve a compelling government interest—in this case, prevention of charitable fraud. "There is a dramatic mismatch…between the interest that the Attorney General seeks to promote and the disclosure regime that he has implemented in service of that end," Roberts says, noting that more than 100,000 charitable organizations are registered in California and that 60,000 renew their registrations each year.

"Given the amount and sensitivity of this information harvested by the State, one would expect Schedule B collection to form an integral part of California's fraud detection efforts," Roberts says. "It does not. To the contrary, the record amply supports the District Court's finding that there was not 'a single, concrete instance in which pre-investigation collection of a Schedule B did anything to advance the Attorney General's investigative, regulatory or enforcement efforts.'" Should the attorney general decide to investigate a particular organization, Roberts notes, he can always obtain donor information via a subpoena or audit letter.

"California casts a dragnet for sensitive donor information from tens of thousands of charities each year, even though that information will become relevant in only a small number of cases involving filed complaints," the Court says. "California does not rely on Schedule Bs to initiate investigations, and in all events, there are multiple alternative mechanisms through which the Attorney General can obtain Schedule B information after initiating an investigation. The need for up-front collection is particularly dubious given that California—one of only three States to impose such a requirement—did not rigorously enforce the disclosure obligation until 2010."

Fears about the consequences of such compelled disclosure are hardly fanciful. The petitioners "introduced evidence that they and their supporters have been subjected to bomb threats, protests, stalking, and physical violence," Roberts notes. In that context, it is rational to worry that major donors could face similar reprisals, a prospect that might deter them from supporting groups that promote causes they favor.

Compounding that concern, California has been amazingly lax in protecting the donor information it collects, which is supposed to be confidential but in practice is not. The Americans for Prosperity Foundation "identified nearly 2,000 confidential Schedule Bs that had been inadvertently posted to the Attorney General's website, including dozens that were found the day before trial," Roberts notes. "One of the Foundation's expert witnesses also discovered that he was able to access hundreds of thousands of confidential documents on the website simply by changing a digit in the URL. The court found after trial that 'the amount of careless mistakes made by the Attorney General's Registry is shocking.' And although California subsequently codified a policy prohibiting disclosure…the court determined that '[d]onors and potential donors would be reasonably justified in a fear of disclosure given such a context' of past breaches."

Roberts says "the gravity of the privacy concerns in this context is further underscored by the filings of hundreds of organizations as amici curiae in support of the petitioners." Those organizations (which include this website's publisher, the Reason Foundation) "span the ideological spectrum, and indeed the full range of human endeavors: from the American Civil Liberties Union to the Proposition 8 Legal Defense Fund; from the Council on American-Islamic Relations to the Zionist Organization of America; from Feeding America–Eastern Wisconsin to PBS Reno." Roberts adds that "the deterrent effect feared by these organizations is real and pervasive, even if their concerns are not shared by every single charity operating or raising funds in California."

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, in a dissent joined by Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan, faults the majority for deeming California's requirement facially unconstitutional rather than limiting its analysis to organizations that can demonstrate a well-grounded fear of reprisals. "The same scrutiny the Court applied when NAACP members in the Jim Crow South did not want to disclose their membership for fear of reprisals and violence now applies equally in the case of donors only too happy to publicize their names across the websites and walls of the organizations they support," she writes.

Sotomayor concedes "there is no question that petitioners have shown that their donors reasonably fear reprisals if their identities are publicly exposed," although she questions "the likelihood of that happening." If the Court "had simply granted as-applied relief to petitioners based on its reading of the facts," she says, "I would be sympathetic, although my own views diverge." Instead, she argues, "the Court jettisons completely the longstanding requirement that plaintiffs demonstrate an actual First Amendment burden before the Court will subject government action to close scrutiny."

The Institute for Justice, which backed the petitioners in this case, takes a different view. "Today's ruling reaffirms vital protections for the rights of privacy and association," says Institute for Justice senior attorney Paul Sherman. "California required tens of thousands of charities to disclose their most sensitive donor information and then mishandled that confidential information so badly that it was easily available to anyone with an internet connection. The Court correctly recognized what a grave threat this requirement posed to the rights of free speech and association."

Show Comments (56)