California's Requirement That Nonprofits Disclose Donor Information Poses a Grave Threat to Freedom of Association

A broad coalition of groups is asking the Supreme Court to overturn the state's policy.

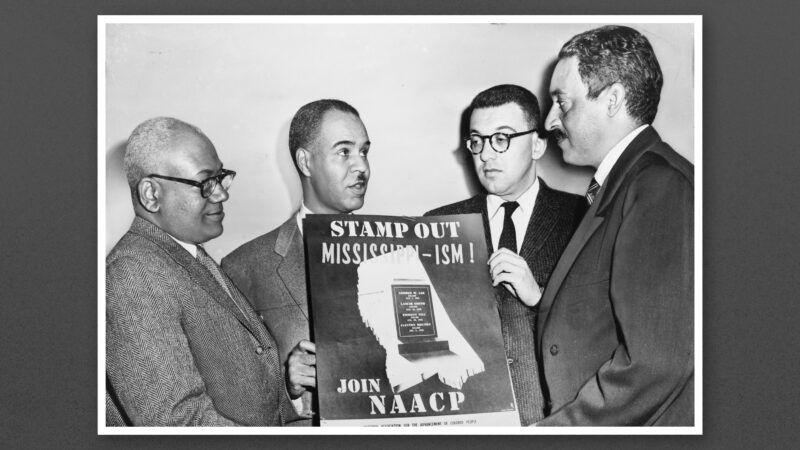

Sixty-three years ago, in a case challenging Alabama's requirement that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) disclose its membership lists, the Supreme Court recognized that such demands can pose a grave threat to freedom of association. In that case and subsequent decisions, the Court established a test for compelled disclosure of organizational information that may result in "reprisals against and hostility to the members": The requirement must be "substantially related" to a "compelling" government interest, and it must be "narrowly tailored" to serve that interest.

As a federal judge recognized in 2016, California's requirement that all nonprofit organizations disclose information about their donors plainly fails that test. But two years later, a panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit reversed that decision, concluding that California's policy passed constitutional muster based on a weaker standard that usually applies only in the context of campaign finance regulation. In Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Becerra, which the Supreme Court will hear later this term, two conservative organizations are asking the justices to overturn the 9th Circuit's decision. They are joined by a remarkably wide range of groups from across the political spectrum, reflecting the significance of the First Amendment threat posed by California's nosiness.

California has long required that charitable organizations registered in the state submit federal tax forms revealing the names and addresses of supporters who have donated more than $5,000. But it did not start aggressively enforcing that requirement until 2010, when the California Attorney General's Office began demanding donor information as a condition of registration. The Americans for Prosperity Foundation (AFPF) objected to that demand, leading to years of litigation that culminated in this Supreme Court case.

The information collected by California, which is listed on an IRS form known as Schedule B, is supposed to be confidential. But in practice, it is not.

As Sandra Segal Ikuta and four other 9th Circuit judges noted in 2018, when they dissented from the appeals court's refusal to rehear the case, the trial evidence "provided overwhelming support" for AFPF's fear that donor data would be publicly revealed, exposing the organization's supporters to harassment for their political views. "State employees were shown to have an established history of disclosing confidential information inadvertently, usually by incorrectly uploading confidential documents to the state website such that they were publicly posted," the dissenting judges said. "Such mistakes resulted in the public posting of around 1,800 confidential Schedule Bs, left clickable for anyone who stumbled upon them." In 2012, for example, "Planned Parenthood become aware that a complete Schedule B for Planned Parenthood Affiliates of California, Inc., for the 2009 fiscal year was publicly posted; the document included the names and addresses of hundreds of donors."

Even when such information was not publicly posted, it could be readily discovered, as AFPF showed by hiring a consultant to test the security of California's Registry of Charitable Trusts. "He was readily able to access every confidential document in the registry—more than 350,000 confidential documents—merely by changing a single digit at the end of the website's URL," Ikuta et al. noted. Even after the state was alerted to this vulnerability and supposedly fixed it, "the expert used the exact same method the week before trial to test the registry" and "was able to find 40 more Schedule Bs that should have been confidential."

Controversial organizations like Planned Parenthood and AFPF have good reason to worry about the consequences of the state's incompetence. "People publicly affiliated with the Foundation have often faced harassment, hostility, and violence," the 9th Circuit dissenters noted. "Supporters have received threatening messages and packages, had their addresses and children's school addresses posted online in an effort to intimidate them, and received death threats."

At a rally in Michigan, "several hundred protestors wielding knives and box cutters surrounded the Foundation's tent and sawed at the tent ropes until they were severed. Foundation supporters were caught under the tent when it collapsed, including elderly supporters who could not get out on their own. At least one supporter was punched by the protestors."

In addition to harassment and violence, AFPF supporters have faced economic reprisals. "After an article published by Mother Jones magazine in February 2013 revealed donor information," Ikuta et al. noted, "protesters called for boycotts of the businesses run by six individuals mentioned in the article. Similarly, Art Pope, who served on the Foundation's board of directors, suffered boycotts of his business."

These threats represent exactly the sort of fallout that the Supreme Court understood could have a chilling effect on the First Amendment rights of NAACP members. That is why the Court said disclosure requirements like Alabama's and California's should be subject to heightened scrutiny. In this case, California did not come close to showing that its blanket demand for Schedule B forms was substantially related to a compelling government interest, let alone that it was narrowly tailored.

California says it needs those forms to guard against fraud. But that contention is hard to reconcile with the fact that state officials let the disclosure requirement lie dormant for many years before they began demanding donor information. AFPF itself was allowed to register in California from 2001 to 2010 without submitting the forms that were notionally required.

"The state requires blanket Schedule B disclosure from every registered charity when few are ever investigated," Ikuta et al. noted. They suggested that the Attorney General's Office could instead "obtain an organization's Schedule B through a subpoena or a request in an audit letter once an investigation is underway without any harm to the government's interest in policing charitable fraud." Since "the state failed to provide any example of an investigation obscured by a charity's evasive activity after receipt of an audit letter or subpoena requesting a Schedule B," they said, it is hard to see why that much more narrowly tailored approach is inadequate to satisfy the government's interest in preventing charitable fraud.

In its Supreme Court brief, AFPF argues that the 9th Circuit panel "misread this Court's precedents as permitting compulsion of donor identities without the need for narrow tailoring." It warns that "upholding California's disclosure requirement would effectively abandon this Court's seminal precedents and let law enforcement prevail virtually every time in demanding donor information." The brief notes that preserving supporters' anonymity "protected the NAACP's members from intimidation by State officials in the Jim Crow South" and reassured "large donors to LGBTQ causes" who "feared the consequences" of being publicly identified.

The Thomas More Law Center, which joins AFPF in challenging California's policy, likewise argues that "all Americans should be free to support causes they believe in without fear of harassment." Yet "the California Attorney General's Office demands that all nonprofits fundraising in the State turn over major donors' names and addresses, then leaks that data like a sieve." In fact, "the Office admits it cannot ensure donor confidentiality, though technology makes it easier than ever to harass, threaten, and defame."

The challenge to California's disclosure requirement is supported by a strikingly wide range of organizations, including a long list of socially conservative groups and nonprofits of every description, ranging from the Animal Legal Defense Fund to the Zionist Organization of America. The supporters also include the American Civil Liberties Union, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the Institute for Justice, the Cato Institute (joined by the Reason Foundation, which publishes this website), the Goldwater Institute, the Pacific Legal Foundation, the National Taxpayers Union, the American Legislative Exchange Council, several gun rights groups, Democracy 21, the Philanthropy Roundtable, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Manufacturers, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the Hispanic Leadership Fund, and the Council on American-Islamic Relations.

This broad coalition, representing all sorts of causes and political preferences, is powerful evidence of the constitutional interests at stake in this case. At a time of bitter partisan differences and seemingly unbridgeable cultural divisions, people on different sides of many issues can at least see eye to eye on the necessity of preventing the government from arming their opponents with confidential information that can be used to punish Americans for exercising their First Amendment rights.

"This is not the time or the climate to weaken First Amendment rights to anonymity," AFPF says. "Social and political discord have reached a nationwide fever. Perceived ideological opponents are hunted, vilified, and targeted in ways that were unthinkable before the dawn of the Internet. As partisan pendulums swing back and forth in governmental offices, and as online campaigns rage against perceived ideological foes, donors to causes spanning the spectrum predictably fear that exposure of their identities will trigger harassment and retaliation far surpassing anything reasonable people would choose to bear. Vindicating freedom of association in this context will therefore mean the difference between preserving a robust culture and practice of private association and charitable giving, versus opening the door to chilling governmental intrusion."

Show Comments (55)