The Media's Lab Leak Debacle Shows Why Banning 'Misinformation' Is a Terrible Idea

How a debate about COVID-19's origins exposed a dangerous hubris

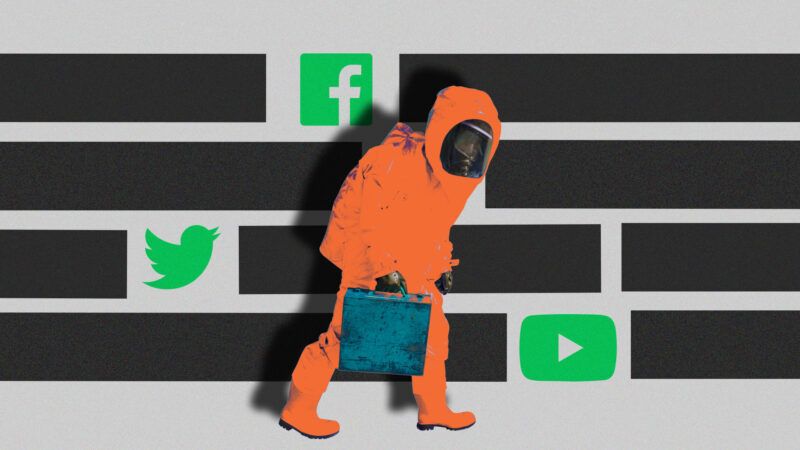

Facebook made a quiet but dramatic reversal last week: It no longer forbids users from touting the theory that COVID-19 came from a laboratory.

"In light of ongoing investigations into the origin of COVID-19 and in consultation with public health experts, we will no longer remove the claim that COVID-19 is man-made or manufactured from our apps," the social media platform declared in a statement.

This change in policy comes in the midst of heated debate about how to respond to the perception that social media is amplifying the spread of false information. For the last several years, journalists and politicians have pushed to police so-called misinformation through various means. Major news organizations have hired mis- or disinformation reporters. Lawmakers such as Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D–Mass.) and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D–Calif.) have urged social media sites to prohibit speech deemed wrong or dangerous—and have sometimes suggested that this should be required by law. More recently, various groups have asked President Joe Biden to establish a federal initiative to combat online misinformation.

But Facebook's concession that the lab leak story it once viewed as demonstrably false is actually possibly true should put to rest the idea that banning or regulating misinformation should be a chief public policy goal.

It's one thing to discuss, debate, and correct wrong ideas, and both tech companies and media have roles to play in fostering healthy public dialogue. But Team Blue's recent obsession with rendering unsayable anything that clashes with its preferred narrative is the height of hubris. The conversation should not be closed by the government and its yes-men in journalism, in tech, or even in public health.

From False Claim to Live Possibility

Consider that Facebook's new declaration sits atop its About page, just above the site's previous policy on coronavirus-related misinformation—dated February 8, 2021—which was to vigorously purge so-called "false claims," including the notion that the disease "is man-made or manufactured." The mainstream media had deemed this notion not merely wrong but dangerously absurd, and tech companies followed suit, suppressing it to the best of their abilities.

"Tom Cotton keeps repeating a coronavirus conspiracy theory that was already debunked," read a February 2020 Washington Post article that criticized the Arkansas senator for departing from the prevailing narrative. Similarly, Politico both mischaracterized Cotton's claims and said the rumor was "easily debunked within three minutes."

But in recent weeks, the lab leak theory—the idea that COVID-19 inadvertently escaped from a laboratory, possibly the Wuhan Institute of Virology—has gained some public support among experts. In March, former Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) chief Robert Redfield said that he bought the theory. (His admission earned him death threats; most of them came from fellow scientists.) Nicholson Baker, writing in New York, and Nicholas Wade, formerly of The New York Times, both wrote articles that accepted the lab leak as equally if not more plausible than the idea that COVID-19 jumped from animals to humans in the wild (or at a wet market). Even Anthony Fauci, the White House's coronavirus advisor and an early critic of the lab leak theory, now concedes it shouldn't be ruled out as a possibility.

This has forced many in the media to eat crow. Matthew Yglesias, formerly of Vox, assailed mainstream journalism's approach to lab leak as a "fiasco." The Post rewrote its February headline, which now refers to the lab leak as a "fringe theory that scientists have disputed" rather than as a debunked conspiracy theory. New York magazine's Jonathan Chait noted that a few ardent opponents of lab leak "with unusually robust social-media profiles" had used Twitter—the preferred medium of progressive politicos and journalists—to promote the idea that any dissent on this subject was both wrong and a sign of racial bias against Asian people.

"Story after story depicted the lab-leak hypothesis as clearly false and even racist," wrote Chait. "The outlets that fared worst were those like the Guardian, Slate, and Vox (which is owned by the same company that owns New York Media), which embraced a 'moral clarity' ethos of forgoing traditional journalistic norms of restraint and objectivity in favor of calling out lies and bigotry."

To be clear, while some circumstantial evidence supports the lab leak theory, there is still no scientific consensus on whether COVID-19 emerged from a research facility, a wet market, or somewhere else. (Moreover, there is considerable confusion about whether the U.S. government was funding the sort of research at the Wuhan Institute of Virology that could have produced COVID-19.) The Chinese government has stymied efforts to investigate the origins of the disease, and it's possible the world will never know the truth.

But many lab-leak foes had not merely called the theory unproven. They had lobbied for the theory's adherents to be effectively silenced. They asserted that anyone discussing it was a conspiracy theorist or even a racist. Indeed, some are still discouraging this conversation.

"I & other AAPIs are increasingly concerned that speculation over the lab leak theory will increase anti-Asian hate," tweeted Leana Wen, a professor of public health and CNN medical analyst, earlier this week. "As we embark on a full scientific investigation, we must take actions to prevent the next escalation of anti-Asian racism."

She did not explain why speculation about the lab leak theory would increase anti-Asian hate to a more appreciable degree than speculation about the wet market theory. The idea is counterintuitive: The lab leak theory indicts a handful of individual scientists and the Chinese government, whereas the wet market theory can be used to indict broader Asian cultural traditions that have often been criticized in the West. And while an apparent surge in anti-Asian hate crimes is at this point taken for granted among professional pundits and politicians, its extent and underlying causes are far from clear. For instance, the Atlanta spa killings are often cited as the prime example of the lethal nature of anti-Asian bias, but no definitive evidence has emerged thus far that racism was a conscious motivating factor in the shootings.

Yet it's clear that a certain segment of lab-leak critics believed two things: 1) the theory would fan the flames of racism, and 2) for that reason, it should be proactively censored. Such is the slipperiness of the misinformation label, which has come to include all sorts of claims that are not straightforwardly false.

When 'Misinformation' Turns Out To Be True

What's true of the debate over COVID-19's origins is also true of countless other policy disputes. When The New York Post published a report on Hunter Biden's efforts to lobby his father on behalf of foreign governments, the media pressured everyone to pretend the story did not even exist. Journalists who did share the article on social media were shamed for doing so, and the uniform assertions that the paper had fallen prey to a Russian disinformation campaign swiftly persuaded both Facebook and Twitter to throttle the story. Later, when it became evident that the information undergirding the story (if not all its conclusions) was accurate, tech companies were forced to admit their error. Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey has apologized repeatedly.

Big Tech takes its cues from the mainstream media, making decisions about which articles to boost or suppress based on the prevailing wisdom coming from The New York Times, The Washington Post, and elite media fact-checkers. (That's according to information I obtained from insiders at Facebook during research for my forthcoming book, Tech Panic.) Social media companies are also wary of government officials, who have shown increasing interest in punishing them for platforming misinformation. Facebook, Twitter, et al. are rationally skittish: Congress has hauled Dorsey, Mark Zuckerberg, Sundar Pichai, and others to Washington, D.C., numerous times to answer questions about why specific pieces of content were allowed to exist. The best example of this was an April 2018 hearing in which Sen. Patrick Leahy (D–Vt.) printed out pictures of Facebook groups, glued them to a poster board, and demanded that Zuckerberg personally explain whether they were Russian in origin.

In February 2021, Democratic Reps. Anna Eshoo and Jerry McNerney, both of California, sent letters not just to tech companies but to cable providers taking them to task for airing outlets that spread misinformation. Later that week, Congress convened a hearing on "disinformation and extremism," where lawmakers discussed whether the failure to purge all false claims about the 2020 election from the internet and television may have contributed to the Capitol riots.

Right-wing spaces are undoubtedly rife with absurd election claims, from the idea that President Trump actually won last year to the recent notion that a coup will restore him to office by August. The spread of election-related falsehoods—for which no one is more to blame than the former president himself—fanned the violence and destruction on January 6.

But some of the early reporting about what transpired at the Capitol also turned out to be false. Most notably, an angry MAGA mob did not bludgeon Officer Brian Sicknick to death with a fire extinguisher, as The New York Times and Associated Press initially claimed. It later emerged that Sicknick had suffered a stroke, yet no one called on Facebook to ban the A.P. The defining characteristic of modern campaigns to police misinformation is naked partisanship.

An Epidemic of Federal Falsehoods

No issue has exposed the one-sidedness of the anti-misinformation drive as thoroughly as the pandemic, which has brought us countless examples of health officials making naive, staggeringly wrong predictions. These have continued to the present day. A few short weeks ago, on March 30, 2021, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky warned of "impending doom" because some states were lifting COVID-19 restrictions too quickly. Thankfully, the doom didn't materialize: Coronavirus cases and deaths have continued to declined precipitously, and now even the CDC has recommended a return to normal for everyone who has received the vaccine.

Trump's advocacy of ridiculous or questionable COVID-19 cures earned widespread denunciation, and also inspired considerable fear that people would start drinking bleach and fish-tank cleaners. (When a man died after consuming the chemical, the media raced to blame Trump. The story subsequently turned out to be much more complicated.)

But millions of Americans spent the pandemic wildly scrubbing surfaces and cleaning their groceries due to bad guidance—what might reasonably be called misinformation— from the CDC. Many public spaces still follow such guidance. A requirement to power-wash desks and classrooms was a sticking point in the school reopening debate as recently as February of this year.

Most charitably, those are examples of experts applying their best judgement and making honest mistakes. But there are also instances of intentional lies. In the pandemic's early stages, Fauci discouraged the use of masks only to abruptly reverse himself later. He later admitted that he was worried there wouldn't be enough masks for hospitals and thus was deliberately evasive on the issue. In January, Fauci again confessed to a purportedly noble lie: He purposely set the herd immunity threshold at a lower level because he didn't think the public could handle the actual number. In any fair accounting, this meets the classic definition of spreading misinformation, yet the media's love affair with Fauci has hardly abated at all.

Meanwhile, progressives keep pressuring President Biden to do something to stem the spread of misinformation. A coalition of advocacy groups that includes PEN America, the Poynter Institute, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and others recently sent a letter to Biden urging his administration to create a federal disinformation task force. Several members of the coalition are generally quite supportive of free speech, and their statement calls for "remaining vigilant against censorship and other threats to free expression." Nevertheless, they want the government to explore potential solutions to the problem of social media companies platforming falsehoods.

If the government really wants to fight misinformation, an important first step would be for its own health officials to stop saying things that are false. If social media companies want to help foster the spread of truthful information—as Zuckerberg emailed Fauci to say last year—they should remember that many supposedly authoritative sources in and out of government have partisan axes to grind.

Any broader effort to shut down conversations that include a great number of lies is likely to inadvertently criminalize some politically inconvenient truth, or something that seemed untrue but later proved prescient—lab leak or no lab leak.

Show Comments (246)