Justice Thomas Wonders When Supreme Court Will Have To Consider Social Media's Private Deplatforming Power

A moot case about Trump blocking tweets leads to concerns that tech companies have too much control over speech.

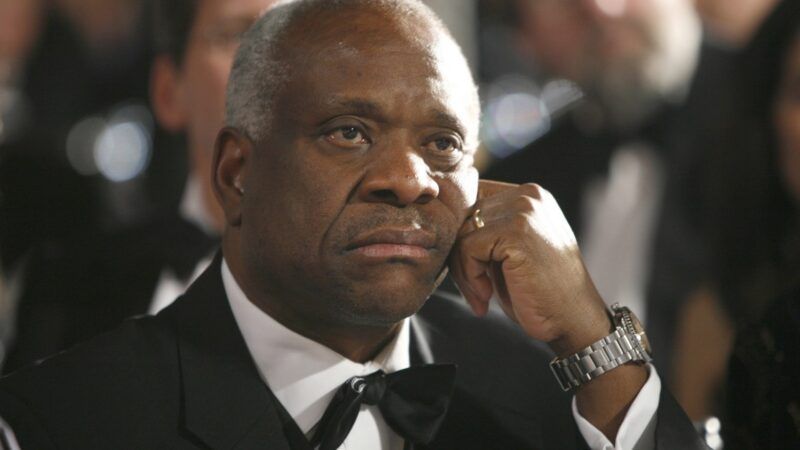

Justice Clarence Thomas this morning suggested that the Supreme Court is on a collision course with online platforms like Twitter and search engines like Google about how much power companies have to decide who may speak.

The context was a unanimous decision by the Supreme Court to order the dismissal of a lawsuit by the Knight First Amendment Institute against former President Donald Trump over whether Trump was unconstitutionally censoring people when he blocked them from tweeting at him. Now that Trump is no longer the president and has been banned from Twitter, the Supreme Court determined the case to be moot.

Thomas, concurring with the decision, decided to write separately to raise questions about the power of Twitter to eject Trump from the platform. He noted the oddness of the concept that a public official's Twitter feed might be considered a "government forum" when interacting with the public, but "a private company has unrestricted authority to do away with it."

Thomas, it seems, is raising points similar to those of some conservative politicians. He believes that there may be something wrong, possibly even unconstitutional, if a private online platform can boot people off or delete comments it objects to. He writes:

Today's digital platforms provide avenues for historically unprecedented amounts of speech, including speech by government actors. Also unprecedented, however, is the concentrated control of so much speech in the hands of a few private parties. We will soon have no choice but to address how our legal doctrines apply to highly concentrated, privately owned information infrastructure such as digital platforms.

Thomas raises the question of whether some of these platforms might be considered by the courts to be "common carriers," utilities like phone lines that serve the public interest. If the courts conclude that they are, then it would be legal, and not necessarily a violation of the First Amendment, for the government to put restrictions on the ability to prohibit people from using the platform.

Thomas also takes note of an argument presented by Eugene Volokh, professor of law at UCLA and co-founder of The Volokh Conspiracy (hosted here at Reason). In January, Volokh considered whether a federal law can run afoul of the First Amendment when it preempts a state law that grants particular free speech protections against private actions. There's a Supreme Court precedent from 1980, Pruneyard Shopping Center v. Robins (Thomas references it in his concurrence), that concluded California had the power to force a shopping mall to allow protesters to engage in advocacy there, even though it was private property.

This precedent is potentially relevant due to the existence of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, which specifies that websites and online platforms have the power to moderate and remove speech they find offensive, even if said speech is protected by the First Amendment. Section 230 is under attack by politicians who want to either force social media platforms to censor content the politicians don't like or, alternatively, force platforms to host content the social media companies themselves don't like.

Volokh has wondered if the Pruneyard precedent could potentially collide with Section 230 if a state passes a law that essentially starts treating social media platforms as "common carriers" and requires them to host users. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis says he wants a law in his state to force social media platforms to host candidates. The law would, on the surface, appear to violate both Section 230 and the First Amendment rights of a platform to control whose speech it wants to host. But Volokh says it may be a little more complicated than that if courts ever embrace the argument that social media platforms, like malls, could be ordered to host certain types of political or activist speech.

Volokh responded to Thomas' concurrence this morning by suggesting that Thomas isn't necessarily calling for tech platforms to be treated as common carriers, but he is noting that it seems like the Supreme Court is going to eventually have to weigh in on these complexities:

As I read it, Justice Thomas is not arguing that platforms are already generally common carriers or government actors under existing legal principles; that argument is quite a stretch, and his analysis seems to me to largely reject that argument, except perhaps when the platforms are restricting speech in response to government threats.

Rather, he is anticipating what might be done through legislation, and whether new state laws that do treat platforms as common carriers (more or less) are going to be seen as blocked by the First Amendment or 47 U.S.C. § 230. (His analysis of the interests involved may also be relevant to whether such state laws violate the Dormant Commerce Clause.) That's an issue the Court will likely have to deal with in coming years.

It's also worth noting that no other justices signed on to Thomas' concurrence, despite the current court's conservative leanings. If there is an interest among other justices to decide whether online platforms can legally be forced to host content, they're not showing it.

Show Comments (71)