L.A.'s Reformist D.A. Promised To Eliminate Hate Crime Enhancements—Until Progressive Activists Gave Him a Call

Some progressives are for criminal justice reform only when it's convenient.

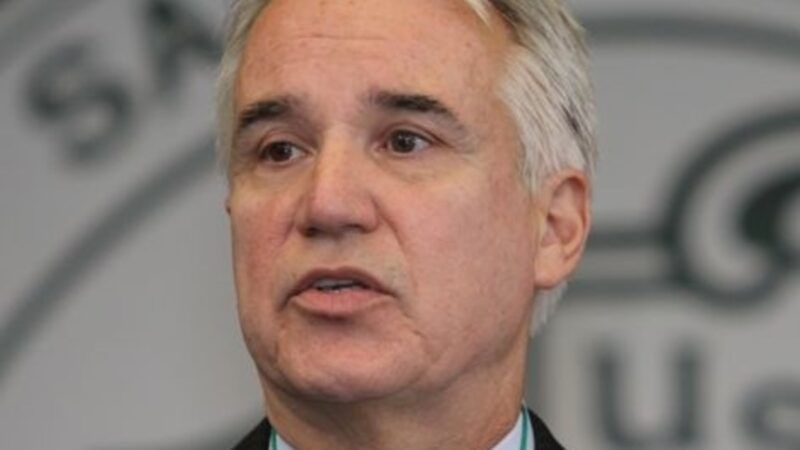

Newly minted Los Angeles District Attorney George Gascón isn't making many friends in L.A. The reformist prosecutor came into office promising to stop prosecuting low-level misdemeanors, to end cash bail, to cease using the death penalty, and to eliminate sentencing enhancements.

To no one's surprise, that to-do list drew conservatives' ire. But the last item on the list also angered some progressives, because it included a pledge to stop upping punishments for alleged hate crimes.

That objection has carried the day. After chatting with some LGBT activists on December 17, the new D.A. announced he would "enable enhancements to be brought in a limited range of circumstances," even as he simultaneously acknowledged that "enhancements have never been shown" to effectively increase safety. In other words, sentencing enhancements will generally be off the table, except when it comes to crimes that the government has deemed particularly hateful.

The irony there is rich. It is progressives who have made criminal justice one of their primary goals, seeking to curtail the carceral state. The U.S. locks people up at higher rates than any other nation in the world, they say, and the system discriminates against people of color. On both points, they are correct.

But when it comes to those who are accused of acting with a particular sort of hate, progressive reformists often pivot to a new target, and that target is the very sort of change they would fight for in virtually any other circumstance.

Calls for criminal justice reform have intensified since the May death of George Floyd, but hate-crime enhancements have historically been immune to such debates. Indeed, some officials have even invoked those calls for reform when handing out enhanced sentences. Two people in Martinez, California, for example, face hate crime charges for painting over a Black Lives Matter street mural in July; Contra Costa County District Attorney Diana Becton explained her decision by calling Black Lives Matter "an important civil rights cause that deserves all of our attention."

Therein encapsulates the problem with hate crimes. An offense, no matter how petty, can receive a more punitive punishment—the exact thing reformers say they oppose—based entirely on subjective ideology. Which ideologies get penalized depends on which ideologies are in power: In a Republican-led effort, the Alabama House this year voted to add police officers to the list of protected classes under hate crime legislation.

"What we probably should have calibrated better is sort of how deeply [the new directive] would be felt by our supporters, by our allies, our [prosecutors]," Joseph Iniguez, the interim chief deputy D.A., told Los Angeles Magazine. "And it wasn't that we didn't think about the community—but we were trying to approach it from a place of, 'Let's just not use this tool because for the most part, the way it's used is disproportionate against people of color.'"

According to the most recent data from the FBI, at least 24 percent of the country's hate crime offenders are black. Since blacks make up 13 percent of the population, such enhancements are, in fact, used disproportionately against people of color. But even if they weren't, you aren't really taking a stance against mass incarceration if you only oppose it for certain races. And you certainly aren't taking a stance against mass incarceration if you get more carceral for certain crimes.

Gascón's "whole goal was to end mass incarceration," Iniguez said. "It still is, by the way." Is it?

Show Comments (40)