California Voters Declined To End Cash Bail. L.A.'s New District Attorney Says He'll Do It Anyway.

Cash bail is as unjust as it is arbitrary.

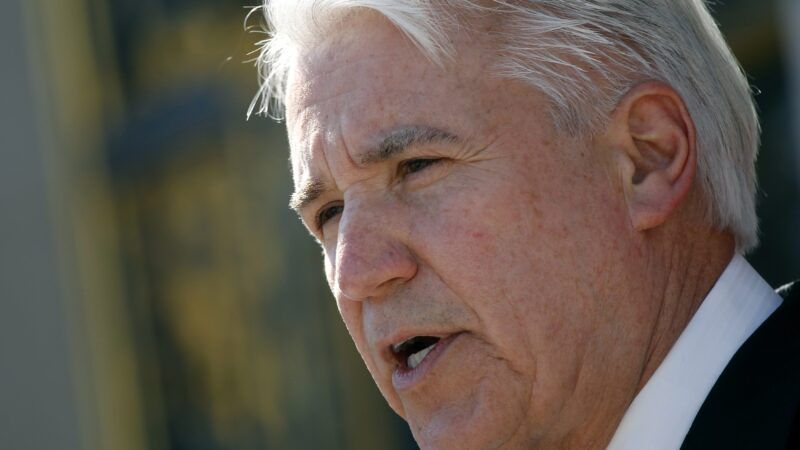

George Gascón was sworn in as the new District Attorney of Los Angeles County on Monday, and he began his tenure with a bang, promising to eliminate sentencing enhancements, nix the use of the death penalty, stop prosecuting certain low-level misdemeanors, and put an immediate end to cash bail.

The latter may well end up being the most controversial when considering that California voters handily rejected Proposition 25, a November ballot measure to abolish cash bail in favor of risk assessments.

But cash bail, as Gascón highlighted yesterday, is as unjust as it is arbitrary, in that it bases an offender's pre-trial freedom on their ability to pay and not on their risk of committing additional offenses or failing to appear for court. Whether a person remains incarcerated while their case works its way through the court thus turns more on personal and family wealth than the defendant's background or factors relevant to the alleged crime. "Money is a terrible proxy for risk posed to society," said Gascón, a former chief of police and San Francisco district attorney. "So today we will end cash bail for any misdemeanor, non-serious, or non-violent felony offense. And I will end bail completely January 1."

He did not expand on if he will eventually replace the current system with a risk analysis program, as Proposition 25 would have done, or explain what other tools courts would have to determine pretrial release.

As Reason's Scott Shackford points out, Gascón and California at large have a compelling model to study in New Jersey, which eliminated cash bail in favor of an adversarial court arrangement. Similar to trial arguments, it is presumed the defendant is innocent and will be released, and it is incumbent upon the prosecutor to convince a judge why that might be unwise.

Gascón also plans to sunset all sentencing enhancements, which are used by prosecutors to secure lengthier terms of incarceration for defendants. Yet those enhancements are often applied capriciously and without a real connection to the crime at hand. L.A. County is no stranger to that: Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) officers last year were caught falsely labeling suspects as gang members in hopes of securing more punitive sentences for crimes that had nothing to do with gang activity.

In a similar vein, Gascón will stop applying California's three-strikes law, which sent thousands of people to prison for life if they committed three felonies, and if two of those were classified as serious or violent. In practice, it meant a defendant could be sentenced to die in prison for something like breaking into a car.

At least 20,000 prisoners will be eligible for release or resentencing, which Gascón said "will save [California] BILLIONS of dollars."

The progressive prosecutor is also likely to take heat for his directive not to pursue charges for certain low-level misdemeanors, such as trespassing, disturbing the peace, driving without a license, prostitution, resisting arrest, criminal threats, drug possession, minors with alcohol, drinking in public, public intoxication, and loitering.

Much of that is a welcome change. Armed agents of the state spend far more time probing nonviolent offenses and minor infractions than they do investigating violent crimes. Those interactions can yield severe consequences, as seen, for instance, with the death of Ramon Lopez, who was held on hot asphalt for several minutes after he was reported for loitering, "sticking his tongue out," and "looking at people's cars."

"For decades we attached felony consequences to low-level offenses," said Gascón.

"It foreclosed job & housing opportunities, exacerbated recidivism, crime & homelessness, & created more victims."

True enough, but Gascón will likely face some objections from concerned citizens, and not without reason. After replacing Vice President-Elect Kamala Harris as San Francisco's top prosecutor in 2011, the city saw a 37 percent increase in property crimes over the course of his eight-year tenure, the bulk of which came from car break-ins. Detractors blamed Proposition 47, a Gascón-led initiative that demoted certain property and drug crimes from felonies to misdemeanors. It's quite possible that his policy backfired; property crime, after all, is not a victimless crime. That doesn't tell the entire story, however: A San Francisco Chronicle investigation found that police, who enjoyed a strained relationship with Gascón, all but stopped arresting people for auto break-ins, only doing so in two percent of cases.

Police unions weren't happy with Gascón's successful campaign. Earlier this year, the LAPD union donated $1 million to a PAC dedicated to his loss; indeed, 72 percent of the donations given to Jackie Lacey, the former L.A. district attorney Gascón defeated in November, came from law enforcement unions.

Those unions so often protect cops at the expense of those they protect and serve. Consider Eric Garner, who was choked to death by a New York Police Department officer in violation of internal policy. But instead of casting the former cop, Daniel Pantaleo, as a bad apple, the union faulted "anti-police extremists" for his termination. Apparently, everyone needs the right to utilize unconstitutional, deadly force.

Gascón seemed to acknowledge that history on Monday. "For decades those who profit off incarceration have used their enormous political influence—cloaked in the false veil of safety—to scare the public and our elected officials into backing racist policies that created more victims, destroyed budgets, and shattered our moral compass," he wrote. "That lie and the harm it caused ends now."

Show Comments (53)