The Guilt or Innocence of the Cop Who Killed Rayshard Brooks Has Nothing to Do With George Floyd's Death

The felony murder charge against Garrett Rolfe hinges on whether he reasonably believed Brooks posed a threat.

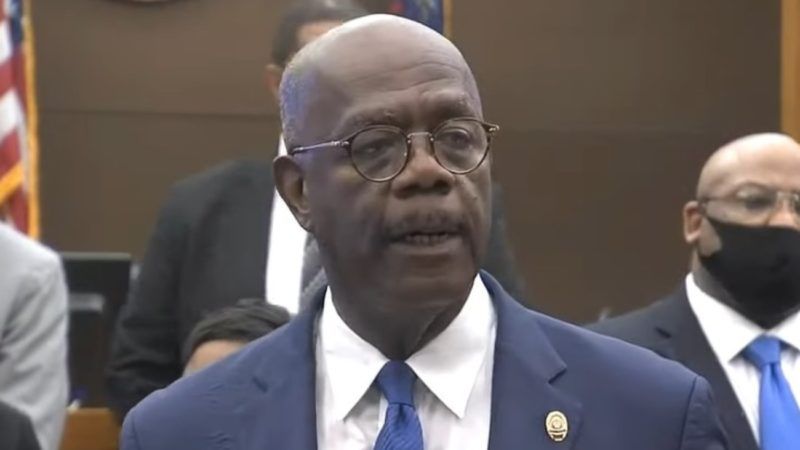

The day after the June 12 shooting of Rayshard Brooks during an arrest for driving under the influence at a Wendy's restaurant in Atlanta, Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms said she did not think Officer Garrett Rolfe's use of deadly force was justified. Rolfe was fired immediately, and yesterday—five days after the incident—Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard announced that the former officer had been charged with felony murder, which is punishable by life in prison or the death penalty, along with 10 counts of assault, aggravated assault, property damage, and violations of his oath.

The swift action against Rolfe was welcomed by Brooks' family and many critics of police abuse. But the timing and context of the dismissal and the charges, along with details of the deadly encounter that Howard glossed over during a press conference yesterday, create the appearance that he and Bottoms rushed to judgment about the shooting. The incident provoked vigorous local protests (including an arson fire at the Wendy's where Brooks was killed) on the heels of nationwide demonstrations in response to the suffocation of George Floyd by Minneapolis police on Memorial Day.

"As protests were touched off across the country by the death of Mr. Floyd, amid a pandemic that has disproportionately affected African-Americans, the demonstrations in Atlanta were especially heated," The New York Times notes. But notwithstanding the justified outrage at Floyd's death, it is important to recognize that some excessive-force cases are more complicated than others. The question of whether Rolfe committed murder hinges on the facts of this particular case, which should not be overlooked to make a statement about holding police accountable, as important as that goal is.

"While there may be debate as to whether this was an appropriate use of deadly force," Bottoms said on Saturday, "I firmly believe that there is a distinction between what you can do and what you should do." Yet "whether this was an appropriate use of deadly force" is the crux of this case, and the mayor had already concluded that it was not, less than 24 hours after it happened.

"Mr. Brooks never presented himself as a threat," Howard told reporters yesterday. The district attorney was referring to what happened after a Wendy's employee called police at 10:33 p.m. last Friday to report that a driver had fallen asleep in the restaurant's drive-through lane. Officer Devin Brosnan arrived nine minutes later, woke Brooks up, and asked him to move his car to a nearby parking space. Seven minutes after that, Brosnan called for another officer to assist him, and Rolfe arrived at 10:56 p.m.

As Howard emphasized, Brooks was polite, cooperative, and even cordial during the first 41 minutes of his interaction with the officers, which included a consensual pat-down, a field sobriety test, and a breath test that put his blood alcohol concentration at 0.1 percent, slightly above the legal limit of 0.08 percent. But things changed dramatically when Rolfe announced that Brooks "had too much drink to be driving," grabbed him from behind, and tried to handcuff him. Howard said Rolfe violated department policy at that point by failing to explicitly inform Brooks that he was being arrested for driving under the influence, an omission that is the basis for one of the charges against Rolfe.

Brooks responded to the sudden transformation of what had until then been a surprisingly friendly encounter by pulling away from Rolfe. He ended up wrestling with the officers on the pavement of the parking lot. They asked him to "stop fighting" and warned him that he would be tased if he did not. When Brosnan drew his Taser and tried to subdue Brooks with it, Brooks grabbed the weapon. After some more wrestling, Brooks stood up, punched Rolfe, and ran away, still holding the Taser. Rolfe ran after Brooks, firing his Taser in an unsuccessful effort to stop him. After Brooks fired Brosnan's Taser at Rolfe, his aim too high to hit the officer, Rolfe drew his handgun and fired three shots, two of which struck Brooks in the back.

Under the Supreme Court's ruling in the 1985 case Tennessee v. Garner, the crucial question about Rolfe's use of deadly force is whether he had "probable cause" to believe that Brooks posed "a significant threat of death or serious physical injury" to Rolfe or others. After reviewing eyewitness reports, physical evidence, and video from dashcams, body cameras, the restaurant's surveillance system, and bystanders' cellphones, Howard concluded that such a belief was not justified by the circumstances.

That conclusion is debatable. As The New York Times noted earlier this week, "officers are trained that they have the right to escalate their use of force if they believe someone is threatening to incapacitate them." Brooks had already taken Brosnan's Taser. If he had managed to use it effectively against Rolfe, the officer might have been thinking, Brooks also could have grabbed Rolfe's gun.

Furthermore, although Tasers are promoted as "less than lethal" weapons, they can be deadly. Howard's own office described the Taser as "a deadly weapon" in a recent case involving an assault by Atlanta police officers on nonviolent protesters.

Howard disputed that potential defense. At the point when Rolfe shot Brooks, the district attorney said, the Taser had already been fired twice, which meant it was no longer effective at a distance and therefore "presented no danger to him or to any other persons." Although Howard assumes Rolfe knew that, it is possible that he did not realize the Taser had been fired twice or that the fact did not register in the heat of the moment.

Howard also said Rolfe violated his oath by firing his Taser at a fleeing suspect, which department policy forbids, and recklessly endangered other people in the parking lot when he fired his handgun, which is the basis for several assault charges against Rolfe. Howard noted that one round hit a Chevrolet Trailblazer, which is the basis for another charge: criminal damage to property.

Lance LoRusso, Rolfe's attorney, vigorously disputed Howard's characterization of the incident. "Mr. Brooks violently attacked two officers and disarmed one of them," he said in a press release. "When Mr. Brooks turned and pointed an object at Officer Rolfe, any officer would have reasonably believed that he intended to disarm, disable, or seriously injure him." That description suggests Rolfe did not necessarily realize Brooks was firing a Taser. According to Howard, the pat-down had discovered a "bulge" in Brooks' pants pocket, but the officers accepted his assurance that it was a wad of bills.

Brosnan is charged with violating department policy and assaulting Brooks by standing on his shoulder as he lay on the ground after the shooting. Brosnan, who recalled standing on Brooks' arm rather than his shoulder, said he did that because he was not sure whether Brooks had a weapon. Rolfe is charged with assaulting Brooks by kicking him after the shooting, which he presumably will argue was justified by a fear of further violence.

"This was not a rush to judgment," said Don Samuel, Brosnan's lawyer. "This was a rush to misjudgment." Samuel said Brooks initially shot Brosnan with the Taser he grabbed from him, causing Brosnan to fall backward and suffer a concussion as his head hit the pavement.

Howard charged Rolfe and Brosnan with failing to promptly treat Brooks' wounds. Samuel denied that, saying Rolfe ran to his car to get a first aid kit "less than a minute" after the shooting and "Devin did what he could to save Mr. Brooks." According to a video-based reconstruction of the incident by The New York Times, Rolfe ran to his SUV a minute after the shooting and called for an ambulance. The Times says the two officers began to "provide medical assistance" at 11:25 p.m., two minutes after the shooting, when Rolfe can be seen bandaging Brooks' torso.

Howard described Brosnan as a "cooperating witness" who was ready to testify against Rolfe, a characterization that Samuel immediately disputed. "We've never agreed to testify," Samuel told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. "We've never agreed to cooperate. We've never agreed to plead guilty."

The newspaper notes that the charges against Brosnan, who has been an Atlanta police officer for less than two years, "were a surprise to many," since he "interacted politely" with Brooks and "didn't reach for his gun" even after "Brooks took off with his Taser." It adds that "the contradiction" between what Samuel said and Howard's description of what Brosnan had agreed to do, along with "other unusual aspects" of the press conference, raised "questions about the speed with which Howard completed his investigation."

The Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI), which "investigates nearly all police shootings in the state," typically "takes between 60 and 90 days to complete probes," the Journal-Constitution says. The GBI has not yet announced its findings regarding Rolfe's shooting of Brooks, which happened less than a week ago. The agency said it was "not aware of today's press conference before it was conducted" and was "not consulted on the charges filed by the District Attorney." The Journal-Constitution notes that "the GBI is currently investigating Howard, who faces a tough runoff election against his former chief deputy prosecutor Fani Willis in August, and his use of a nonprofit to funnel at least $140,000 in city of Atlanta funds to supplement his salary."

Philip Holloway, a former prosecutor and local criminal defense attorney, told the paper Howard is "clearly not interested in what the GBI has to say," adding, "It will be very interesting if GBI doesn't come up with the same conclusions that he did. If not, they will become star witnesses for defense."

Under Georgia's felony murder statute, prosecutors have to show that Rolfe caused Brooks' death while committing a felony—in this case, aggravated assault, which he allegedly committed by firing his gun at Brooks. In other words, the same conduct that killed Brooks is also the predicate felony for the murder charge, which means prosecutors do not have to prove that Rolfe intended to kill Brooks. Yet the penalty—death or life imprisonment—is the same as the penalty for intentional, premeditated murder.

If Rolfe's use of deadly force was justified, he did not commit aggravated assault when he fired his weapon and he therefore cannot be guilty of felony murder. Jurors historically have been extremely reluctant to second-guess police officers' judgment in cases like this, although that may change because of the impact that George Floyd's death and other recent travesties have had on public opinion. Leaving aside the double standard that police tend to benefit from when it comes to the use of deadly force, the question is whether prosecutors can prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Rolfe did not have probable cause to believe, given the circumstances, that Brooks posed "a significant threat of death or serious physical injury."

Howard argues that Rolfe's demeanor at the time of the shooting suggests he was not really afraid of Brooks. "At the time that the shot was fired, the utterance made by Officer Rolfe was, 'I got him,'" he said at the press conference. "The demeanor of the officers immediately after the shooting did not reflect any fear or danger of Mr. Brooks, but their actions really reflected other kinds of emotions."

Notwithstanding Howard's purported insight into the officers' hearts and minds, their lawyers will argue that they dealt professionally and appropriately with a violent suspect who had repeatedly assaulted them, who had fired a Taser at both of them, and who may have continued to pose a threat even after he was shot because they were not sure whether the Taser was the only weapon they had to worry about. Whether or not that story is true, a jury might very well find it plausible enough for reasonable doubt about the prosecution's case.

Brooks' death during what should have been a routine DUI arrest is obviously horrifying. No one deserves to be killed by the police because he drove a car after he had a little too much to drink—a low-level misdemeanor that typically is handled with sanctions such as fines, probation, community service, and license suspension. Rolfe and Brosnan arguably had several opportunities to avoid that deadly outcome.

Brooks would still be alive if Brosnan had followed his initial inclination to let him pull out of the drive-through lane and take a nap in a parking space. "He was not an experienced DUI investigator, so that's why he called Officer Rolfe in," Howard said. "He indicated to us that he was somewhat surprised that it accelerated into an actual arrest, because he thought that the situation might have been resolved before then."

Brooks repeatedly volunteered to lock his car and walk to his sister's house, which was nearby. He would still be alive if the officers had let him do that. At the same time, one can imagine the outcry against such lenience if Brooks had later returned to his car and gotten into an accident. And despite Howard's suggestion that the incident could have been resolved without an arrest, department policy leaves no such discretion in DUI cases. It says "an officer will write a citation and make a physical arrest when a driver is cited for…driving under the influence of intoxicating alcoholic beverages where the level of intoxication is .08% or more."

The charge that Rolfe violated department policy by failing to explicitly tell Brooks that he was being arrested for DUI may seem picayune. But Brooks might not have resisted his arrest if Rolfe had not sprung it on him so suddenly. One second, he was chatting amiably with the officers, and the next he was being grabbed and handcuffed.

Finally, Rolfe could have let Brooks go when he ran away and tracked him down later based on his driver's license and car registration. When Rolfe decided to chase Brooks, it seems, he was simply trying to detain him and complete the arrest. There was no reason to think that Brooks at that point posed any danger to the general public. But Rolfe was not obligated to let Brooks go, and what happened next, by Rolfe's account, was determined by what Brooks did: He fired the Taser at Rolfe, who according to his lawyer did not know whether it was a stun gun or perhaps a firearm that the pat-down had missed.

What was Rolfe's state of mind at that moment, and was it justified by the circumstances? Those are the questions a jury will have to confront. They have nothing to do with George Floyd's death or the general problem of police brutality. But it sure looks like those issues have colored the public and official reaction to the shooting.

Show Comments (167)