Newspaper Lobbyists and Encryption Foes Join the Chorus Against Section 230

How the press learned to stop worrying and love censorship.

The Department of Justice has joined the campaign against Section 230, the federal law that enables the internet as we know it. Its effort is probably part of Washington's ongoing battle against encrypted communications. And legacy news media companies are apparently all to happy to help them in this fight.

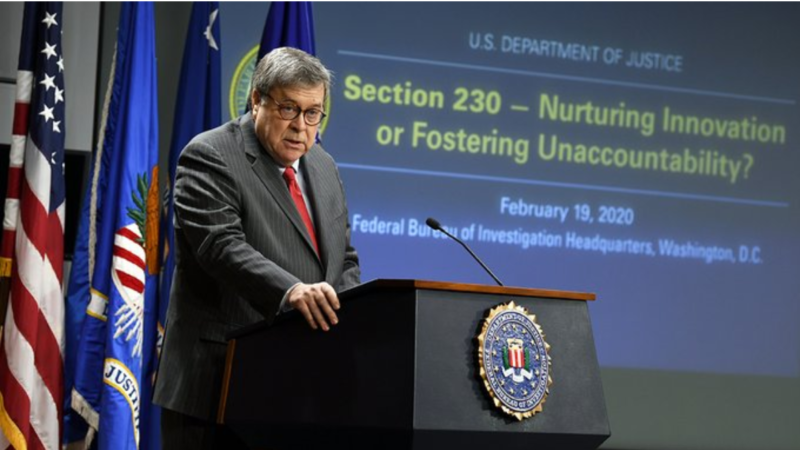

On Wednesday, the U.S. Department of Justice held a "public workshop" on Section 230. Predictably, it wound being up a greatest hits of the half-truths and paranoid bellyaching commonly employed against this important law.

Section 230 prevents digital companies from being automatically treated as the speaker of any third-party speech they assist in putting online. It also allows companies to moderate content without becoming liable for it. The law was passed in 1996 to address the fact that the then-dominant web companies felt forced to choose between very strictly gate-keeping or allowing a free-for-all if they wanted to avoid civil lawsuits and criminal liability over user-generated speech.

Section 230 has never prevented the Justice Department from enforcing federal criminal statutes against online violators, as many have misleadingly argued. (For a quick debunking of more Section 230 myths, see this video.) It acts as a shield against civil lawsuits and against state and local criminal charges.

U.S. Attorney General Bill Barr opened the event yesterday by saying that "criminals and bad actors now use technology to facilitate and expand the scope of their wrongdoing and the victimization of our fellow citizens."

This is the same line of talk Barr has used against encrypted communication.

Barr invoked child exploitation as one reason to reexamine Section 230. But the statute was passed explicitly to address this issue, as part of a larger law concerning "communication decency" and online pornography. It provides the legal framework that allows companies to actually try to keep exploitative content offline. And nothing in Section 230 prevents the enforcement of federal laws against child pornography and other forms of sexual exploitation.

"Section 230 has never prevented federal criminal prosecution of those who traffic in [child sexual abuse material]—as more than 36,000 individuals were between 2004 and 2017," points out Berin Szoka in a post dissecting draft anti–Section 230 legislation proposed by Sen. Lindsey Graham (R–S.C.). Graham's bill would amend Section 230 to lower the standard for legal liability, so tech companies needn't "knowingly" aid in the transmission of illegal content to be found guilty in civil suits and state criminal prosecutions; they'd merely have to be deemed to have acted "recklessly" in such matters as content moderation or product design. The legislation would also create a presidential commission to offer "best practices" on this front. Taken together, Szoka sees this as a back door to banning end-to-end encryption by declaring it reckless. (More on that bill from First Amendment lawyer Eric Goldman here.)

Barr's remarks yesterday didn't explicitly mention giving government backdoors to spy on people. Instead, he played up several popular (and wrong) arguments against Section 230, such as the claim that it's responsible for "big tech" restricting online speech or that it prevents us from having "safer online spaces." Lurking in these comments is the schizophrenic proposition girding a lot of Section 230 opposition: that getting rid of it would somehow permit freer speech online and keep online spaces "safer" and more palatable for everyone.

Barr also engaged in the kind of social media exceptionalism common among Section 230 critics, insisting that online platforms today are so radically different than their predecessors as to warrant different rules. In doing so, he suggested that walled-off internet services like AOL had less control over content than their current counterparts and implied that Section 230 only protects social platforms and "big tech" companies.

In reality, Section 230 applies to even the smallest companies and groups (and is more important for ensuring their existence than it is for big companies, whose army of lawyers and moderators have a better chance of weathering a post-230 onslaught of lawsuits from users). And it applies to many types of digital entities, including behind-the-scenes web architecture (such as blogging platforms and email newsletter software), consumer review websites, crowdfunding apps, podcast networks, independent message-boards, dating platforms, digital marketing tools, email providers, and many more.

Barr said Wednesday that the Justice Department was "not here to advocate for a position." Yet everything else in his speech suggested otherwise, including his waxing about how civil lawsuits against tech companies (of the sort disallowed by Section 230) could "work hand-in-hand with the department's law enforcement efforts."

He concluded the talk by saying "we must remember that the goal of firms is to maximize profit, while the mission of government is to protect American citizens and society."

So: tech companies bad, government good. Got that?

Not everyone in Washington buys this simplistic argument, thank goodness. In a recent Washington Post op-ed, Sen. Ron Wyden (D–Ore.), who co-authored Section 230, explains how the law protects individual speech rights and pointed out that major media and tech companies have in fact been working with regulators against the law.

"Occasionally," writes Wyden, "Congress actually passes a law that protects the less powerful elements of our society, the insurgents and the disrupters. That's what it did in 1996 when it passed [Section 230]." He explains that the law "was written to provide legal protection to online platforms so they could take down objectionable material without being dragged into court."

"Without 230, social media couldn't exist," adds Wyden. Neither could movements like Black Lives Matter or #MeToo. "Whenever laws are passed to put the government in control of speech, the people who get hurt are the least powerful in society."

People often pretend government regulation of speech is somehow neutral. But defining permissible speech can change greatly depending on subjective and partisan priorities. Without Section 230, what online content is permissible and who gets punished would be determined not by an array of private companies but by a centralized political institution with the power to imprison, not just deplatform.

"I'm certain this administration would use power to regulate speech to punish its enemies and protect its allies," writes Wyden at the Post. "It would threaten Facebook or YouTube for taking down white supremacist content. It would label Black Lives Matter activists as purveyors of hate."

A Democratic administration would approve and disfavor different sorts of speech. But we would still have a partisan and centralized command over the bounds of online communication. And either way, the spoils will go to the big tech companies that are best able to lobby, contribute, curry favor, or otherwise game the system.

Powerful entities like Facebook, Disney, and IBM are all fighting to re-write the rules for digital speech in their favor. A recent New York Times article detailed how the fight against 230 is being led by a coalition of old media companies resentful of Google, Facebook, etc. and other corporations whose business has been bit into by digital tools. For instance, Marriott has been campaigning against Section 230 as a way to stick it to vacation rental platforms like Airbnb.

"The easiest lever to hurt tech companies that a lot of people see is 230," Stanford Law School professor Daphne Keller told the Times.

Mike Masnick suggests this illustrates the "concept of political entrepreneurs v. market entrepreneurs. One of them builds better, more innovative products that increase consumer welfare and increase the overall size of the pie by making things people want. The other uses its enormous power and political connections to pass regulations that hinder competitors who have innovated."

The companies now opposing Section 230 are "the legacy companies which have fallen behind, which have not adapted, and which are using their political will to try to suppress and destroy the open systems that the rest of us now depend on," Masnick writes.

One such example from this week is the News Media Alliance, formerly known as the Newspaper Association of America, which "represents approximately 2,000 news organizations across the United States and Europe." At the Justice Department's Wednesday workshop, the group's president, David Chavern, testified that "Section 230 has created a deeply distorted variable liability marketplace for media." This, he said, is bad not just "for news publishing but for the health of our society."

Chavern insisted this wasn't merely about news industry profits. But he ended his testimony by endorsing a "Journalism Competition & Preservation Act," which he said "would allow news publishers to collectively negotiate with the platforms and return value back to professional journalism," which…sure makes it sound like this is about news industry profits.

And when entrenched industry profits line up with the feds' surveillance agenda? That's when we're invited to kiss the open internet goodbye.

Show Comments (110)