State Regulators Punish Doctor for Cutting a Pain Patient's Opioid Dose and Dropping Him After He Became Suicidal

The decision by the New Hampshire Board of Medicine suggests state officials are beginning to recognize the harm caused by the crackdown on pain pills.

A New Hampshire doctor recently got into trouble with state regulators because of the way he treated a pain patient. But in a refreshing twist that suggests state officials are beginning to recognize the harm caused by restricting access to pain medication, the New Hampshire Board of Medicine reprimanded and fined the doctor not for prescribing opioids but for refusing to do so.

In May, the New Hampshire Union Leader reports, Joshua Greenspan, a Portsmouth physician certified in pain management and anesthesiology, signed a settlement agreement with the state medical board that included a reprimand, a $1,000 fine, and "at least 12 hours of education in prescribing opioids for pain management and in pain management record-keeping." The settlement stems from a June 2018 complaint in which a patient reported that Greenspan, "after treating him for years and prescribing the same dosages of pain medication, suddenly reduced his medications, which led to increased pain and anxiety, and suicidal ideations."

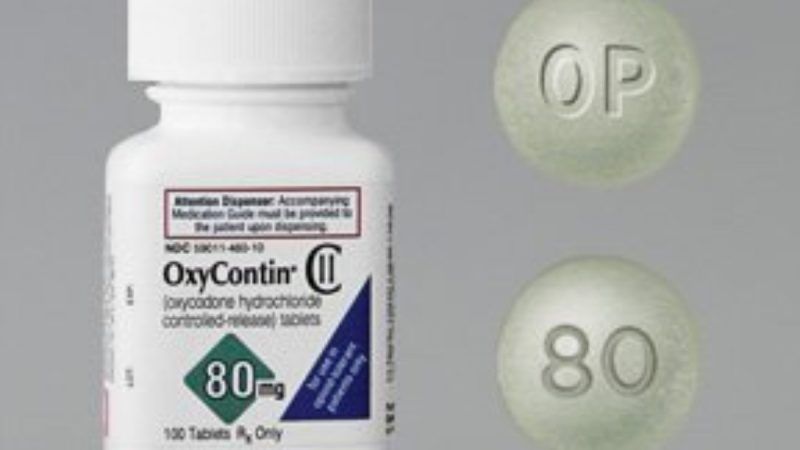

According to the settlement agreement that Greenspan signed, the patient "had suffered from chronic pain for many years, stemming from a number of different sources, including back and leg pain from a fall, testicular pain after a surgery, neck and back pain from a motor vehicle accident, and chest and shoulder pain following coronary bypass surgery." A previous doctor had prescribed the patient two 80-milligram tablets of OxyContin, an extended-release formulation of oxycodone, plus four 30-milligram tablets of immediate-release oxycodone, per day.

Although Greenspan initially continued those prescriptions, in April 2018 he informed the patient that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) had imposed a cap on opioid prescriptions of 90 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day. Based on the conversion factor used by CMS, the patient was receiving more than four times that amount: 420 MME per day.

But as the medical board noted, that 90-MME rule, which did not take effect until the beginning of this year, is not a hard ceiling. Instead the CME requires pharmacists to consult with prescribing doctors before filling prescriptions that total 90 MME or more per day. Greenspan's confusion is understandable, however, since CME initially proposed a stricter limit, from which it retreated in response to strong objections from doctors and patients.

The 90-MME threshold is based on 2016 prescribing guidelines from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that have been widely misinterpreted as requiring dose reductions for patients who already exceed that arbitrary cutoff, even if they have been functioning well on those doses for years. That perception has led to involuntary dose reductions and patient abandonment across the country. The CDC belatedly repudiated that misunderstanding of its advice in a statement and a journal article last April, three years after issuing the guidelines and one year after Greenspan erroneously told his patient that the federal government was demanding dose reductions.

After Greenspan cut the patient's daily dose by 40 milligrams (60 MME), the patient found that his pain was no longer well-controlled. According to the settlement agreement, the patient repeatedly complained about unrelieved pain and on one occasion visited a hospital because he was having a "tough emotional time." Greenspan "made no referrals or recommendations regarding these issues, but instead reduced the patient's dosage by another 20 mgs." The Union Leader describes what happened next:

Later that year, the patient failed a pill count and was admitted to a hospital for threatening suicide.

That's when the doctor told the patient he was no longer comfortable prescribing opioids for him and would no longer treat him. He also "reported his concerns about (the patient's) well-being" to the local police department and the man's primary care doctor, according to the settlement. He also sent a prescription for an opioid withdrawal drug to the patient's pharmacy.

The board found that Greenspan's handling of the case violated ethical standards of professional conduct.

That conclusion highlights how concerns about the "opioid crisis," reinforced by real or perceived demands from the government, have perverted the doctor-patient relationship, making physicians agents of the war on drugs, which is inconsistent with their professional duties. The medical board's decision suggests that New Hampshire regulators understand the dangers of those conflicting priorities. Perhaps not coincidentally, New Hampshire is also fighting the Drug Enforcement Administration's demands for warrantless access to prescription records.

Bill Murphy, a local pain treatment activist, told the Union Leader the resolution of the complaint against Greenspan "sends the right message to physicians in New Hampshire," who need to understand that "the guidelines are just that—guidelines—and not hard-and-fast rules." At the same time, Murphy expressed sympathy for doctors who feel pressured to reduce opioid prescriptions and worry that they could lose their licenses, livelihoods, and even their liberty if they are identified as outliers. "I think in the end they do want to help people," he said. "They feel like they're caught between a rock and a hard place."

[This post has been updated with additional details from the settlement agreement.]

Show Comments (49)