The Romance of Oppression

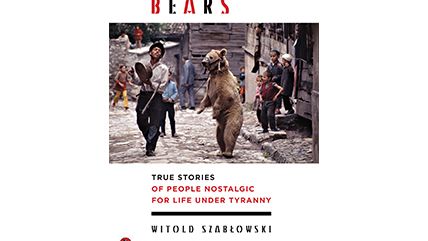

Dancing Bears: True Stories of People Nostalgic for Life Under Tyranny, by Witold Szablowski, translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, Penguin Books, 233 pages, $16

When I was a little girl, my country held its first democratic election after more than a decade of military rule. The bald, mustachioed general who had led Pakistan for my entire life had died in a plane crash a few months earlier. A woman, the daughter of a previously slain prime minister, led her party to an electoral majority, and on a pleasant December morning we watched her sworn into office. This, we were told, was history. This was democracy. This was the beginning of freedom.

The people of my city, Karachi—particularly those who had voted for the new prime minister—decided to use their freedom right away. Large groups of them climbed onto motorbikes and into the backs of pickup trucks; they took over the city streets, waving flags and shooting firearms in the air. Everyone else, including my family, sat inside their houses, afraid. Within a few hours of the arrival of "freedom," my father and grandfather and mother were nostalgic for the days of tyranny. Dictatorship, they decided, was safer and more orderly than the chaos of democracy.

That sort of nostalgia is the subject of Dancing Bears, a new book by the Polish journalist Witold Szablowski. Refreshingly, the dancing bears promised in the title are not coy clickbait or mere metaphor but actual bears. In the style of the great Polish journalist Ryszard Kapucinski, Szablowski offers a roving, acutely observed narrative on the truths, lies, and absurdities that accompany political transitions, especially the one from communism to democracy.

A dancing bear is not merely held captive. It has an iron ring painfully inserted into its nose, which the bear master uses to lead the animal around. This provides a persistent (and, in the trainer's view, crucial) reminder of who is boss. We learn this from Gyorgy Marinov, a trainer who in the first few pages of the book swears that he loved his bear, Vela, "like she was human" and that he made sure she never wanted for bread or chocolates or strawberries.

In 2007, as a condition of joining the European Union, Bulgaria's bears had to be freed. The process of liberating the animals, in which the poor gypsies who own them are made to give them to a nongovernmental organization called Four Paws, makes for the same sort of spectacle as do transitions to democracy in previously unfree places. In one story involving the Stanevs, a leading family in the bear-dancing profession, an animal named Misho refuses to get in the cage that is to transport him to freedom. The gathered photographers start getting edgy, and so do the gathered representatives from Four Paws. The family appears terrified. Finally, the youngest Stanev, a boy of 4, says something in Misho's ear, and the bear follows him into the waiting cage, as if hypnotized.

The scene is, of course, the opposite of what the onlookers expected. In the rhetoric of newly realized democratic freedom, the bears symbolize everything that was wrong with the old system: cruelly captured; treated poorly; the rings in their noses as painful, one Bulgarian journalist tells Szablowski, as "a rusty nail through a man's penis."

A facility in Belitsa is the setting for a rehabilitative effort, where the bears are introduced to freedom in "gradual stages," going from cave to fenced enclosure where they can smell but not touch other bears. They are taught to hibernate, their health is monitored, and a dentist is brought from Germany to examine and care for their gums.

The bear experiment is a total failure. Even after years at Belitsa, few of the bears develop the instincts that would permit them to survive in the wild. A worker tasked with sterilizing the animals sums it up: "Unfortunately, our bears not only have the smell but also the mentality of captives. For twenty or thirty years they were used to having somebody do the thinking for them, providing them with an occupation, telling them what they had to do."

The story of the dancing bears works well as an allegory for democratic transition. Its contours may be inexact—the Czech Republic, for instance, has transitioned out of Stalinism with much more ease than, say, Belarus—but that is forgivable given its pliability in revealing just how complex a society's interface with freedom really is. The familiarity of past constraints, even deeply oppressive ones, can tempt many people away from the risks inherent in political choices. And it is not just the Polish and the Pakistani who have suffered from smashed expectations when freedom proves more arduous and unwieldy in reality than it seemed when it was abstract and coveted.

In the Trump moment, doused as it is in fears of democratic fragility, Szablowski's wry amusement at the bears, their owners, and the charade of teaching them freedom becomes imbued with a macabre sense of doom. In ensuing chapters, he explores Cuba, Ukraine, even London. Each time, he encounters similar "discrepancies" that call into question the dominant narratives of the success of one or another political system.

Ana, a Cuban dance teacher whose entire family (and dance studio) occupy a few hundred square feet, insists that she was so troubled by pre-Communist inequality levels that, even when Fidel was taking away everything her family owned, she felt "he was doing the right thing." But in the end, it's not her words but those of a German black marketer that stick: "If Cuba opens up to the world, you'll be able to sell them anything." The dance teacher and others Szablowski encounters on the island challenge the bear metaphor: Here are people still living under Communism who are engaged in secret side enterprises even as they insist on the glory of their leaders.

No promise of sudden liberation, delivered at the hands of either democracy or revolutionary communism, delivers up freedom or equality in the neat packages that everyone expects. Szablowski peels off the rhetoric to reveal the scummy realities beneath. The moments of reckoning, when reality is finally confronted, do not spare even those who have taken their good fortunes for granted. The United States has already begun weighing the value of freedom against the seeming security of social guarantees. In Europe, the dwindling of welfare benefits following the dwindling of postwar reserves has brought on similar seductions by would-be tyrants or their approximations.

It is not, then, simply those raised in subjugation and newly freed, bumbling away at democracy in Pakistan or Poland, who are vulnerable to the temptation to exchange liberty for the easy relief of having someone else make the decisions. Trading away their freedoms in order to get walls and fences to protect them from the other bears (er, people), Americans and Europeans have also become adept at justifying their own oppressions, the nose rings they wear. We may not be free, they say, but look at our chocolates and strawberries.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Romance of Oppression."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Trading away their freedoms in order to get walls and fences to protect them from the other bears (er, people), Americans and Europeans have also become adept at justifying their own oppressions, the nose rings they wear. We may not be free, they say, but look at our chocolates and strawberries.

The USA and Europe are not alike. When you compare the two like you have, you just come off as silly.

Reason is really going whole hog on the borders=tyranny thing.

How about "trading away their freedoms in order to get laws and courts"

Or "trading away their freedoms in order to get defensive armed forces"

Unless someone's an anarchist, why don't those arguments work against having laws, courts, and military defense?

Babies and bathwater...

I earned $5000 last month by working online just for 5 to 8 hours on my laptop and this was so easy that i myself could not believe before working on this site. If You too want to earn such a big money then come and join us.

CLICK HERE?? http://www.Aprocoin.com

Americans who actually wear nose rings would prefer government oppression to freedom. At least the ones I've met.

I am getting $100 to $130 consistently by wearing down facebook. i was jobless 2 years earlier , however now i have a really extraordinary occupation with which i make my own specific pay and that is adequate for me to meet my expences. I am really appreciative to God and my director. In case you have to make your life straightforward with this pay like me , you just mark on facebook and Click on big button thank you?

c?h?e?c?k t?h?i?s l?i?n-k >>>>>>>>>> http://www.Geosalary.com

After hearing that Trump's wall is like the Berlin Wall, a nice lady calmed me down with her soothing video.

ASMR Epic facial.. in bed

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BX3chW8oDhI

Were any of the bears eventually reunited w their (human) families?

Doubtful. If they had just removed the painful rings, then what's the big problem? Many animals are a bad idea to have as a pet, and a bear is one of them, but these bears did seem to want to stay with the gypsies. When they were taken away, I'm sure there were plenty of gypsy tears for Borat.

Removing the nose ring would probably be more painful than leaving it in place. If it's not pulled on, it's just a piercing.

First off Islam is not compatible with a civilized society. An educated ,civilized society is required for self rule.

Shoots this story all to hell. Islam needs a tyrant to keep the idiots that follow Muhammad from killing each other.

+1

Amusing how the whiners are so upset at an imperfect analogy. Knee-jerk reactions, hey, we're not Europe, it's a different kind of wall, etc. Trump derangement is real. Pretty good illustration of the book's premise.

At any rate, I want to know what the little boy whispered to the bear, so I bought the Kindle edition.

The United States has already begun weighing the value of freedom against the seeming security of social guarantees.

It began that shit in the 1930s, if not before.

The Woodrow Wilson Adminstration- 1913 - 1921.

TR has a sad.

"Fragile democracy" under Trump must refer to the deep state creation of "Russian collusion" in order to unseat a democratically elected president, right? Right?

I've always felt the left likes the "freedom" provided by a government that makes all your choices for you. While the right wants the freedom to make their own choices good or bad

The left likes the false guarantee of "freedom from" (hunger, etc) rather than "freedom to".

Choices are oppressive. Having only one kind of everything makes us so much more free.

Well I like using a different deodorant every day of the month and can't find more than 23 choices anywhere.

It's a shame there is no prominent 'right' party in the US. What we have are two major left parties that differ only on which parts of government should be bigger and which freedoms the I dividual should reliquinish to the state. For their own good of course.

The difference is "freedom from" vs. "freedom of".

I quit working at shoprite and now I make $30h ? $72h?how? I'm working online! My work didn't exactly make me happy so I decided to take a chance? on something new? after 4 years it was so hard to quit my day job but now I couldn't be happier.

Heres what I've been doing? ,,,

CLICK HERE?? http://www.Theprocoin.com

Escape from Freedom", sometimes known as The Fear of Freedom outside North America, is a book by the Frankfurt-born psychoanalyst Erich Fromm, first published in the United States by Farrar & Rinehart in 1941. In the book, Fromm explores humanity's shifting relationship with freedom, with particular regard to the personal consequences of its absence. His special emphasis is the psychosocial conditions that facilitated the rise of Nazism."

Escape from Freedom

Start working at home with Google! It's by-far the best job I've had. Last Wednesday I got a brand new BMW since getting a check for $6474 this - 4 weeks past. I began this 8-months ago and immediately was bringing home at least $77 per hour. I work through this link, go to tech tab for work detail.

>>>>>>>>>> http://www.GeoSalary.com