Houston Narc Who Lied to Justify a Deadly Drug Raid Had Been Accused of Perjury

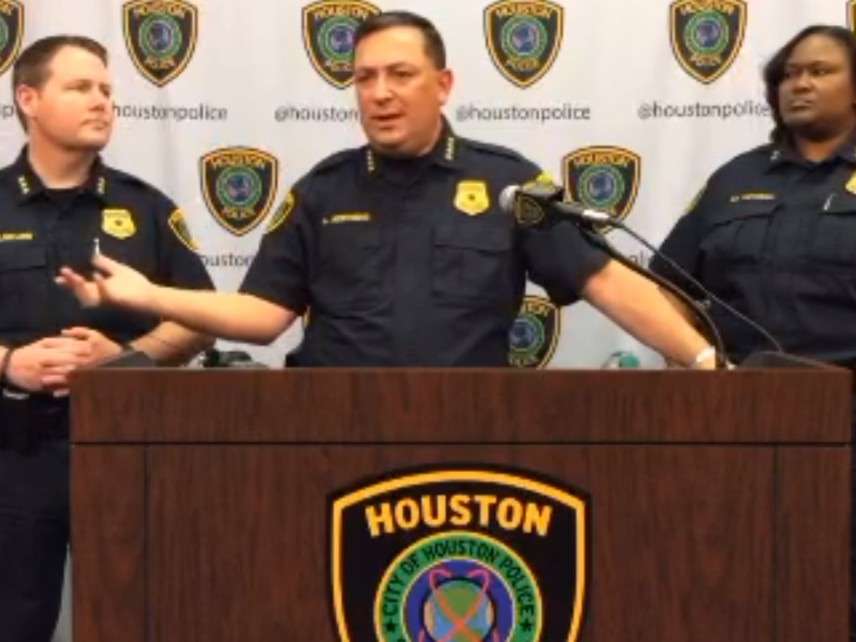

"I don't have any indication it's a pattern," Police Chief Art Acevedo says.

The day after the January 28 drug raid that killed a middle-aged couple and injured five undercover narcotics officers, Houston Police Chief Art Acevedo lavished praise on Gerald Goines, the 34-year veteran who had been shot in the neck after breaching the door and entering the house to assist his wounded colleagues. "He's a big teddy bear," Acevedo said. "He's a big African-American, a strong ox, tough as nails, and the only thing bigger than his body, in terms of his stature, is his courage. I think God had to give him that big body to be able to contain his courage, because the man's got some tremendous courage."

Acevedo struck a different note on Friday, when he described Goines as a liar who had broken the law and embarrassed the department by inventing the heroin purchase that was the pretext for the raid, during which police killed Dennis Tuttle and Rhogena Nicholas in their home at 7815 Harding Street. But as Keri Blakinger and St. John Barned-Smith reported on Friday night in the Houston Chronicle, there were warning signs that Goines was not a paragon of police professionalism long before he invented a confidential informant and a controlled buy to justify the no-knock search that put him in the hospital but did not discover any evidence of drug dealing.

"Previous allegations surfaced about Goines in at least two drug buys, with the officer accused of lying under oath and mishandling drug evidence, and questions arising about his use of a confidential informant," Blakinger and Barned-Smith write. One case, where witnesses contradicted Goines' testimony tying the defendant, Otis Mallet, to a stash of crack cocaine, is still making its way through the courts. "The new evidence discovered in this case shows that Officer Goines testified falsely and that no drug deal, as described by Goines, took place," Mallet's lawyer wrote in a brief. "Mallet was convicted based on Goines' perjured testimony."

Blakinger and Barned-Smith also note incidents in which Goines was reprimanded for unprofessional behavior, including threats of violence, and a confrontation in which Goines was shot while undercover by a man who believed "the officer was menacing him with a weapon." A grand jury declined to indict the man, which suggests his fear was reasonable in the circumstances. "Despite the occasional reprimands," Blakinger and Barned-Smith say, "Goines generally garnered positive evaluations."

Here is the best defense of Goines a former supervisor could muster: "He was a good narcotics officer. He's not corrupt, but he's lazy with his paperwork. He has a history of not doing his reports until afterwards." Even if Goines was never "corrupt" in the sense that he was on the take, sloppiness like this is a warning sign of someone who is cutting corners in a way that can not only jeopardize cases but get people killed, as happened here.

Acevedo says police will be examining a sample of Goines' cases to see if there is a pattern of dishonesty, which would cast doubt on any convictions in which the officer's testimony played a role. At this point, Acevedo said on Friday, "I don't have any indication it's a pattern and practice." Maybe he should read the Houston Chronicle.

While Acevedo's view of Goines has evolved, he is not ready to modify his portrayal of Tuttle and Nicholas as scary heroin dealers. A reporter at Friday's press conference noted that relatives and neighbors "told us…consistently, 'These were not drug dealers. These were nice people. Sure, they may have smoked some pot, but…we've known them for 30, 40 years, and this is not who they were.' And it turns out, they were right."

Acevedo pushed back. "We all have seen people that murder people," he said. "We've all seen people that molest their kids. We've all seen people that have done some horrific things. And guess what the neighbors always have said? 'Oh, my God. I never knew. I thought they were the nicest guys.' So I'm not going to go there with you, and I'm not going to make any conclusions on that until we've finished the investigation."

Except that Acevedo already has drawn conclusions by claiming that "the neighborhood thanked our officers" for the raid "because it was a drug house" and "a problem location." Even after the faked warrant was revealed, Acevedo insisted that "we had reason to investigate that location," and "the investigation continues to show that." But the only evidence he has been able to cite, aside from Goines' fabricated "controlled buy," is a January 8 call in which "the mother of a young woman" reported that her daughter "was in there doing heroin." Goines' subsequent "investigation" was so slipshod that he did not even know the names of the people who lived in the house.

Acevedo condemns Goines' invention of probable cause yet seems to assume the accuracy of all the other information he's been fed about the case. He cites the supposed gratitude of "the neighborhood" as evidence that Tuttle and Nicholas were heroin dealers yet dismisses the accounts of actual neighbors who have said not only that the couple was perfectly nice but that they never noticed any suspicious activity at the house—the sort of activity that had to be occurring for the place to be locally notorious in the way Acevedo claims it was.

As I've said before, this operation would have been reckless and senselessly violent even if Tuttle and Nicholas were selling drugs. But it looks like the only evidence police had on that point was a tip from an anonymous woman and the fabrications of a dishonest narc, neither of which was sufficient to establish probable cause for a search. Why is Acevedo still calling Tuttle and Nicholas "suspects" when they were clearly the victims of an illegal home invasion?

Show Comments (81)