2015: The Year in Fear

Criminals, terrorists, and madmen with guns-how fears of violence reshaped American politics

We live an age of unprecedented danger. The country is being battered by a nationwide crime wave. Subversives are waging a guerrilla war on cops. ISIS threatens the very existence of the United States, and its agents are infiltrating the homeland through our porous southern border. Even when the outsiders and the outlaws aren't menacing you, you aren't secure: That boy next door who looks just like your kid might be the next madman to join the epidemic of mass shooters.

Or at least that's the impression you may have gotten this year. The truth is a bit less scary.

While some cities, such as Baltimore and Washington, have indeed seen big spikes in murder this year, many other cities have not; the nation as a whole looks likely to have had a relatively small hike in homicides, and crime overall may actually decrease. (We will not have the full crime statistics for 2015 for several months; I'm drawing here on preliminary analyses by the Brennan Center and FiveThirtyEight.) And it's far too early to conclude that any national shift marks a reversal in America's long decline in violent crime, as opposed to being one of the small bumps that have periodically appeared in the course of that slide.

Meanwhile, unless something really crazy happens on December 31, American police are coming to the end of their second safest year ever, at least as far as deliberately inflicted violence is concerned. Overall, the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund estimates that the number of cops killed in the line of duty by firearms fell 14 percent from 2014 to 2015. And there's no sign of an unusually high number of officers dying in ambushes, execution-style killings, or the other sorts of assaults you'd expect in an actual war on cops.

ISIS obviously intends to murder as many Americans as it can, and after the attacks in Paris and San Bernardino it is hardly surprising that people are afraid of it. But the group is in no sense an "existential threat," no matter how many politicians and pundits use that phrase. Here in the U.S., the Islamic State seems so far to have been better at inspiring copycats than establishing cells.

And mass shootings? You can slice and dice the relevant numbers in a variety of ways, but the most complete study of the subject, released by the Congressional Research Service in August, shows just a slight recent increase in the number of such crimes, and that looks more like the product of year-to-year volatility than a steady trend upward. And though they have taken center stage in the debate over gun control, mass public shootings remain one of the rarest forms of firearm crime.

In other words: Yes, there are threats out there. But this isn't an age of unprecedented danger. It's a time of manageable risks.

I'm not going to try to argue that 2015 saw substantially more fear than other years. It's hard to think of a time when fear was not a central force in our culture. What changes is the forms that the fear takes and the targets at which it is directed. In 2015, public anxieties about violence—particularly those acts of violence that might be classified as terrorism and/or as mass shootings—repeatedly reshaped our politics:

• At the beginning of 2014, criminal justice reform was moving slowly forward, having gradually gathered steam at the state level before finally percolating into Washington. Thanks to a coalition of libertarians concerned with freedom, evangelicals concerned with redemption, and bean-counters concerned with the budget, this was a transpartisan push involving Republicans as well as Democrats. As politicians made those modest but welcome changes, a more militant set of movements in the streets—Black Lives Matter, Copwatch, a wide range of local groups—called for a more radical rollback of the carceral state.

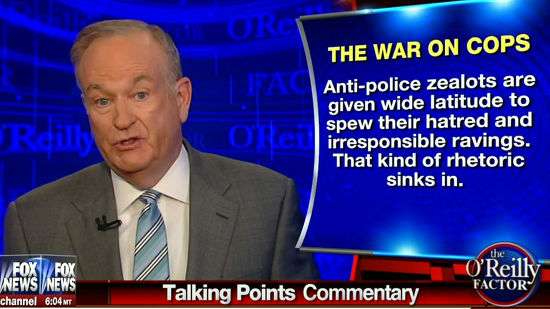

At the end of 2015, a backlash is in full swing. Right-wing tabloids, talk shows, and politicians have invoked the perennial legend of a "war on cops," and they have repeatedly blamed this alleged war on the movement for police accountability. On national level, criminal justice reform is increasingly seen as a Democratic issue. The Republican Party's loudest voices are spouting Agnew-era law and order rhetoric, and conservative media outlets have taken to making absurd comparisons between Black Lives Matter and the Ku Klux Klan.

• At the beginning of 2014, the public was so fed up with the country's seemingly eternal wars that a plurality of Americans told Gallup that it had been a mistake not merely to send soldiers to Iraq but to send troops to Afghanistan after 9/11. The hawks had just failed to pull the country into the fighting in Syria, and pollsters would soon be showing that Americans were no more enthusiastic about getting drawn into a war in Ukraine. The U.S. hadn't turned pacifist—a majority still supported the drone war—but non-interventionist sentiments were at a record high. A Pew poll showed 52 percent agreeing that "the U.S. should mind its own business internationally and let other countries get along the best they can on their own," with just 38 percent disagreeing. This was unprecedented: Even in the immediate aftermath of Vietnam, the disagreers had narrowly outnumbered the agreers.

At the end of 2015, a majority of the public supports the use of ground troops—not just drones or military advisers—against ISIS. That surprising turn of opinion on Afghanistan reversed itself this year, with 54 percent now supporting the decision to enter the Afghan war. And if you don't want a new war abroad, there's still a good chance you favor a new war at home: Thanks to the fear of terrorist infiltrators, we've reached the point where the frontrunner for a major party's presidential nomination can call for halting all Islamic immigration to the country without losing support.

• At the beginning of 2012—I'm reaching back a little further for this one, because the cycle on the Democratic side doesn't always follow the same schedule as the cycle among the Republicans—the Dems had spent more than a decade essentially ignoring gun control on the national level. Both right-leaning Blue Dogs and left-leaning Netroots had generally learned to live with the Second Amendment, and President Barack Obama wasn't making any effort to pull them toward tighter restrictions. With the Supreme Court affirming that the Constitution protects an individual right to bear arms, the topic seemed settled.

At the end of 2015, gun control hasn't simply returned as a Democratic crusade, with all three of the party's major presidential candidates endorsing new restrictions and with Obama reportedly preparing to expand background checks by executive order. It has converged with the larger crime and terrorism scares, letting liberals embrace measures they might have a harder time accepting if they weren't framed as gun issues. Presidential wannabe Martin O'Malley, for example, has tried to shed his law-and-order past and present himself as a fervent supporter of criminal justice reform. But he has also endorsed enhanced gun penalties that would expand rather than reduce incarceration. Worse still: After the San Bernardino massacre, the White House opportunistically called for ending gun sales to people on the no-fly list (or possibly—it wasn't entirely clear—the entire terror watch list). Instead of trying to bring an end to a list infamous for including a large number of non-terrorists and for denying people their due-process rights, leading Democrats now wanted to extend the number of rights the people on the list would lose. And they were happy to engage in the most cynical sorts of fear-mongering rhetoric ("If you're too dangerous to board a plane, you're too dangerous to buy a gun") to get it.

None of these trends are irreversible, and there are countervailing forces to all of the above. It's notable, for instance, that even as gun control has returned as a trendy liberal crusade, Pew's polls show American support for gun rights going up, not down. And according to an ABC News/Washington Post survey published earlier this month, 53 percent of the country now opposes a ban on "assault weapons," the first time that position has commanded a majority since the pollsters started asking the question back in 1994. Needless to say, a fair amount of that isn't a rejection of fear so much as an alternate form of it: Many people think guns should be more easily accessible precisely because they're afraid of crime or terrorism and want the power to defend themselves. But the form a fear takes matters. There is a substantial cultural difference between wanting weapons in widespread hands and preferring that they be concentrated in the hands of the state.

Similarly, it's telling that the medium currently channeling Republican voters' fears of foreigners—Donald Trump—is a relatively reluctant warrior, at least in comparison to establishment darlings Marco Rubio, Jeb Bush, and Chris Christie. Amid his revolting calls to target the innocent relatives of terrorists, his ridiculous plans to seize Iraq's oil, and all his foolish chest-beating about Muslims, Trump has also condemned the Iraq war and absorbed at least some of its lessons. "We have done a tremendous disservice, not only to the Middle East, we've done a tremendous disservice to humanity," he said at one GOP debate. "The people that have been killed, the people that have wiped away, and for what? It's not like we had victory. It's a mess. The Middle East is totally destabilized. A total and complete mess. I wish we had the $4 trillion or $5 trillion. I wish it were spent right here in the United States, on our schools, hospitals, roads, airports, and everything else that are all falling apart." Given Trump's willingness to adjust his positions to fit his base's preferences, the fact that he keeps saying things like this implies that even the most nationalist elements of the electorate are wary of war. Ted Cruz, too, has mixed his spasms of over-the-top belligerance (he says he would "carpet bomb" the Islamic State) with opposition to Rubio's hyper-interventionism. Cruz and Trump aren't Ron Paul—even Rand Paul isn't Ron Paul—but they aren't Dick Cheney either. The prospects for a less interventionist foreign policy don't look as good as they did two years ago, but anti-warriors still have room to maneuver.

We're living in a backlash moment, but backlashes aren't always permanent. Who knows which way the arrow of fear will be pointing in another two years' time?

Show Comments (15)