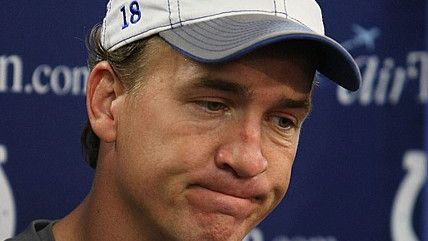

If Peyton Manning Used HGH to Recover From a Broken Neck, Should We Really Care?

It's time to rethink the stigma surrounding this "performance-enhancing drug."

A documentary report released by Al Jazeera last weekend,

titled "The Dark Side," implicates Denver Broncos quarterback Peyton Manning in a potential reputation-destroying performance enhancing drug (PED) scandal.

The report claims Manning's wife received shipments of human growth hormone (HGH) in 2011, while the presumably squeaky-clean future Hall of Famer and serial pitchman was convalescing from a broken neck.

Manning has vigorously denied the allegations, as have most of the other star athletes alleged to have received PEDs from Charlie Sly, the primary source for the report. Al Jazeera described Sly as a pharmacist, but he appears to have never been more than an intern for the Guyer Clinic, and he has since recanted everything he said in the documentary, where he was recorded on hidden cameras bragging about the services he provided to his superstar athlete clients, in an apparent attempt to recruit new clients.

A popular player with a savvy media touch, some have suggested Manning is getting the benefit of the doubt far more than has been afforded grumpier and more outwardly arrogant players accused of PED usage, like Barry Bonds or Roger Clemens. But this is nothing new, look at the scorn heaped on the loathed Alex Rodriguez when it was revealed that he was on a list of failed drug tests from 2003 (which were supposed to remain secret and anonymous) and juxtapose that with the sympathy bestowed on the beloved David Ortiz when it was revealed that his name appeared on the same list. Sport might consist of contests of skills and performance, but it is also very much a competition of popularity, and some are better-suited to win at that game than others.

Manning might be telling the truth or he might be lying through his teeth. If it's the latter, it would hardly be the first time a beloved athlete defiantly wagged a finger while pronouncing his innocence, only to be outed as a fraud.

The question is, when it comes to HGH, should we really even care? Sure, it's banned by almost every sports league, but it also appears to be a miracle of modern medicine that actually aids healing, as opposed to the widely-prescribed painkillers preferred by polite society which only mask the effects of injury and frequently enable even greater long-term suffering.

The moralizing of one drug regimen over another simply makes no sense. Why is it preferable for injured NFL players to be so loaded with Percocet and cortisone that they're "playing numb" rather than engage a newer, less-understood form of medicine that bears no risk of opiate addiction?

Former Reasoner Radley Balko made "The Case for HGH" back in 2008:

The league has banned HGH (on very little evidence), allegedly to protect its players from the harm it allegedly does to their health. But the game of football itself is causing debilitating, potentially life-threatening injuries to players, and we think little of it. These injuries are the entirely predictable result of the slobber-knocking hits that make the game so much fun to watch, both live, and from the six different angles in various highlight packages on SportsCenter.

So we're okay with trusting players to take the risks to their health that come with actually playing football. But we draw the line at letting them use artificial drugs to help them recover more quickly from those injuries. Because that might be dangerous. Or it might benefit players who are using PED's for non-medical purposes.

The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) wasted no time in overreacting to "The Dark Side," calling for "increased collaboration with the leagues and their players' associations to discuss appropriate enhancements that could be made in support of clean athletes." But as Tommy Craggs noted in Deadspin back in 2011, the WADA "is an organization of shrieking for-profit hysterics who still talk about banning caffeine."

Craggs added:

Nevertheless, HGH testing has been covered in the press primarily as a matter of union intransigence in the face of the league's supposedly common-sensical wish to rid the game of the PED scourge. But for the million-and-first time, the performance-enhancing properties of HGH are still an open question, and more to the point, an NFL season without PEDs is an NFL season that ends about half-past mini-camp. (Back in August, when the league first announced plans to implement HGH testing, the lads at Pro Football Talk rightly said it was "more about public relations than anything else," then bizarrely added that the NFL "deserves kudos"—as if policy should be graded on its effectiveness as brand management, not on its actual merits…)

More recently at Deadspin, Tim Marchman wrote about former New England Patriots player Rodney Harrison (now a popular broadcaster on NBC) speaking on the air Sunday night about how his use of HGH (for which he was suspended in 2007) helped him heal from a chronic groin injury. But, Harrison added, it was bad, it was a mistake, think of the children!:

I look at my kids and other kids that look up to me and now I have to tell them why I did it. And maybe I can use this opportunity to let them know it's not worth it. Point blank, period. It's just not worth it.

Marchman takes Harrison to task for insulting our (and the children's) intelligence regarding "the delimiters arbitrarily placed around certain kinds of medicines":

By talking about how off-label use of a prescription drug helped him stay healthy and then following on with a solemn non sequitur about what a horrible mistake it was. Harrison was right in line with the usual branding play here. Think Mark McGwire tearfully going on about what a bad idea it was to take drugs that by his account allowed him to stay on the field despite injuries that had him seriously considering retirement.

One guy with a vested interest in sports performance who's not interested in any pearl-clutching over HGH is Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban. This past Monday, Cuban was asked by the hosts of TMZ Sports if he would approve of legalizing the use of HGH for athletes to recover from injuries. Cuban replied:

Oh yeah, absolutely. I mean, look at it: we say it's ok for people to get LASIK for their eyes. That's performance enhancing. And there's always the chance that something can go wrong. We say that you can get Tommy John surgery, or any surgery for that matter is performance enhancing. Torn ligament? Fix it. Is it better than new? Possibly, with rehabbing it can be better than new. We don't say don't do it because it can be performance enhancing. We say, let's do what's right to get you healthy again.

Cuban is putting his money where his mouth is, dipping into his multi-billion dollar fortune to finance research at the University of Michigan that will test the effects of HGH on healing anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries, which are normally career-enders or at the very least, performance-debilitating.

ESPN's Bonnie D. Ford writes:

The Michigan study could begin to pull HGH from the shadows if, as the researchers hope, it helps prevent the muscles around the knee joint from weakening to a point of no return. Recombinant (synthetic) HGH is a pharmaceutical hot button, controversially championed by the anti-aging industry and still poorly understood in many ways. Its legal uses are restricted in the United States and many other countries, limiting the drug's commercial potential and discouraging research into possible new therapeutic applications.

The fantastic, funny and informative 2008 documentary Bigger, Stronger, Faster (available to watch in full on Youtube) takes on the puritanical opposition to PEDs, and makes apt comparisons between athletes seeking an edge and world-class symphony musicians taking anti-anxiety medications before an important performance. In a New Yorker podcast debate, Malcolm Gladwell made the case for "complete liberalization and complete transparency" regarding professional athletes' use of PEDs, adding that such information would allow him "to reach my own conclusions as a fan about how to evaluate their performance."

Below you can watch Reason TV's video about disgraced ex-cycling champion Lance Armstrong, perhaps the most reviled PED cheater in all of sports, and why his refusal to make excuses about taking drugs to help his teammates or that he didn't know what he was taking is his truly unforgivable sin.

Show Comments (123)