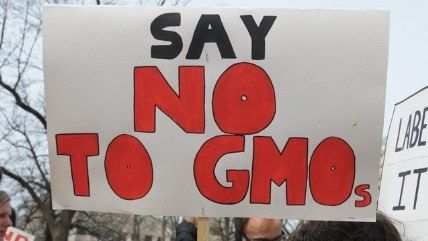

Why Congress Shouldn't Act on GMOs

Let the Supreme Court rule on mandatory labeling.

This month it's become increasingly clear that political debates over GMO labeling mandates may be coming to a head. Reports suggest there will be a compromise in Congress on GMO labeling by the end of 2015.

Generally, this is something that many supporters and opponents of government-mandated GMO labeling alike have wanted for some time. But both sides want far different outcomes. And the rub is that no one seems to know just what a compromise might entail.

"New bipartisan life has been breathed into the national GMO labeling debate," Farm Futures reported last week, "but many are left wondering what it could include."

When isn't the devil in the details?

This past summer, the House passed a bipartisan GMO-labeling bill that seeks largely to assuage food industry fears over state labeling laws.

The House bill, which I referred to here as "flawed," would prohibit the federal government and the states from enforcing any mandatory labeling of foods that contain GMO ingredients and permit the voluntary use of GMO-free labeling claims and the use of claims pertaining to GMO ingredients alike.

If the bill only went that far, I'd be inclined to support it. Instead, it also prohibits food producers from touting the safety of their foods based solely on whether or not their food contains GMOs. Tout away either way, I say.

More problematically, the bill would also require the federal government to "establish a non-bioengineered food certification program" and set national standards for the labeling of non-GMO food.

The precedent for the House bill is the USDA's takeover of organic labeling earlier this century. That process made a mess of organic labeling. It's been beset with controversies that have shaken consumer confidence in organic labels.

"The truth is that most federal labeling schemes are flawed at best, and often involve conflicts and compromises that rob meaning from the label," I wrote in a 2013 piece extolling the virtues of private labeling choices. "The USDA's widely panned takeover of organic labeling in this country is perhaps the best example."

Creating a new USDA bureaucracy and crushing successful, existing market-based labeling efforts, including the Non-GMO Project, wouldn't benefit consumers one bit.

That's why, instead of supporting the House bill, I urged the Supreme Court to strike down Vermont's first-in-the-nation GMO labeling law once that case makes it to the Court—as it likely will if Congress doesn't muck things up—and effectively put the question of mandatory GMO labeling to rest once and for all.

It appeared for a while that might happen. The House bill hasn't gained traction in the Senate.

Now, though, the Senate is working on its own bill. The bipartisan effort is spearheaded by Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.), who worries—like many House colleagues—that food producers forced to comply with dozens of dueling state laws will have to raise prices for consumers.

"I share the concern about the difficulty in doing business across our country if 50 different states have 50 different standards and requirements and frankly, it won't work," Sen. Stabenow said recently.

Stabenow's language closely tracks that of the Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA), which opposes mandatory labeling rules and supports efforts in Congress to rein in existing and potential state labeling laws, and which supported the House bill. In a press release last spring, the GMA cautioned against "a 50-state patchwork of GMO labeling policies that will be costly and confusing for consumers."

The Senate bill would appear likely to distinguish itself from the House bill in some important ways. Just how different, and how important those differences will be, is what's unclear to date. But here are hints.

According to Agri-Pulse, Stabenow says she wants a bill that balances "disclosure and transparency" with assurances it won't "stigmatize biotechnology."

Whatever the end result, it's one the food industry will likely support. That's because Congress has shown overwhelmingly that it has no interest in forcing food makers to label foods that contain genetically modified ingredients.

We need less—not more—politicization of food. Yet Congress appears inclined to find a political solution to what is a legal problem that can and should be settled by the Supreme Court.

Show Comments (21)