Spilled Milk

A brief history of the dairy lobby's unwholesome influence on the U.S. Supreme Court

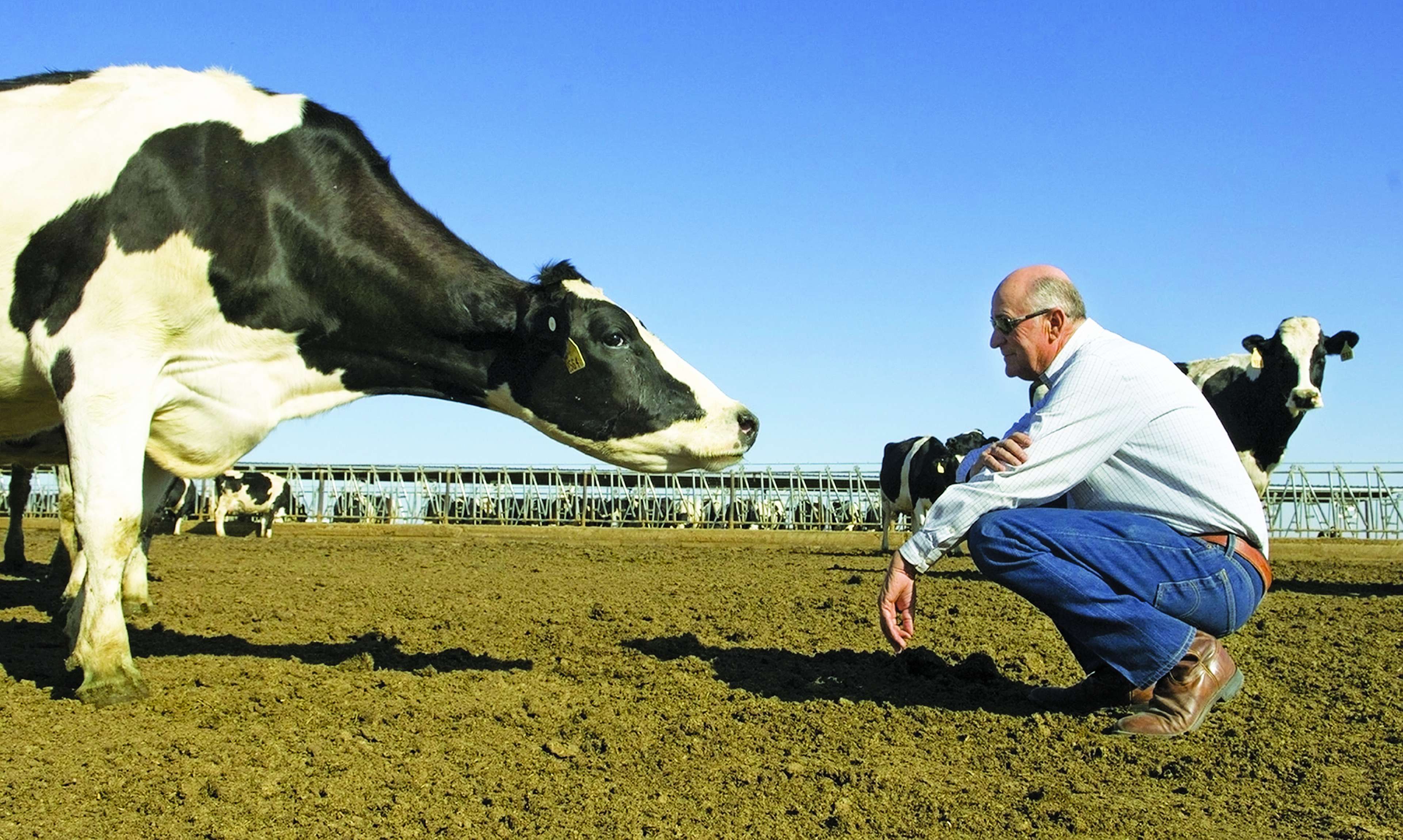

In December 2006 The Washington Post profiled an upstart Arizona dairy farmer named Hein Hettinga. His claim to fame was developing a clever business plan that allowed his farms to lawfully bottle and sell their own milk for as much as 20 cents less per gallon than the minimum price set by a federal law that has been in place since the New Deal. Not surprisingly, Hettinga's low-priced milk was a big hit with consumers. It practically flew off the shelves at Costco.

That's when things turned sour. As the Post put it, "a coalition of giant milk companies and dairies, along with their congressional allies, decided to crush Hettinga's initiative. For three years, the milk lobby spent millions of dollars on lobbying and campaign contributions and made deals with lawmakers, including incoming Senate Majority Leader Harry M. Reid (D–Nev.)."

Those lobbying efforts bore fruit in the form of the Milk Regulation Equity Act. Among other things, this federal statute imposed new minimum milk pricing rules on all producer-handlers operating out of Arizona that distribute at least 3 million pounds of fluid milk per month. In practical terms, Hettinga's operation, Sarah Farms, was the only outfit in the entire state fitting that description. Uncle Sam effectively singled out Sarah Farms for abuse.

In response, Hettinga filed suit in federal court, charging the federal government with violating his constitutional right to earn a living. In April 2012 a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit upheld the law, requiring the upstart dairy farmer to impose a federal price hike on his unlucky customers.

But there was a twist. Though the judges ruled unanimously that "longstanding Supreme Court precedent readily dispenses with [Hettinga's] argument," two of the three judges who voted against Hettinga filed a separate concurring opinion in which they denounced the very legal precedents that forced their hands. This case "reveals an ugly truth," wrote Judge Janice Rogers Brown, joined by Chief Judge David Sentelle: "America's cowboy capitalism was long ago disarmed by a democratic process increasingly dominated by powerful groups with economic interests antithetical to competitors and consumers. And the courts, from which the victims of burdensome regulation sought protection, have been negotiating the terms of surrender since the 1930s." Still, because she was only a lower court judge, Brown concluded, she was duty-bound to follow the Supreme Court's noxious precedents.

Hettinga v. United States was a revealing case in more ways than one. Not only did the key legal precedents cited by Brown involve judicial surrender to special-interest legislation, but those cases—just like Hettinga's—also involved an established industry triumphing over an upstart competitor who sought to entice consumers with an attractive and affordable alternative.

In other words, if you want to understand the unsavory state of economic liberty in America today, look no further than the dairy lobby's unwholesome winning streak in federal court.

I Can't Believe It's Not Butter

Our distasteful story begins back in 1869, when a French chemist named Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès invented an affordable butter substitute called oleomargarine. By using vegetable oil instead of milkfat, he created a cheap, butter-like substance that proved surprisingly popular with French eaters. Better known to us today as margarine, the new product became something of a sensation in late 19th century Europe and America. But while consumers liked it, U.S. dairy farmers were less than pleased at the prospects of a new competitor. In fact, it wasn't long before the industry began demanding that the "unhealthy" new product be outlawed altogether.

The Pennsylvania state legislature dutifully followed suit, passing several laws banning the manufacture and sale of margarine, including one 1883 statute specifically enacted "for the protection of dairymen." Five years later, in a taste of trouble to come, the Supreme Court affirmed the Keystone State's regulatory crackdown.

"Every possible presumption is in favor of the validity of the statute," declared Justice John Marshall Harlan, invoking the principles of judicial deference in his majority opinion in Powell v. Pennsylvania. In Harlan's view, the Court had no business second-guessing the regulatory judgments of democratically accountable officials. If the merchants and manufacturers of Pennsylvania (or any other state) hoped to sell "wholesome oleomargarine as an article of food," Harlan wrote, "their appeal must be to the legislature, or to the ballot-box, not to the judiciary."

Four decades later, Harlan's deferential judgment would come bubbling back to the surface in a landmark New Deal victory for protectionist regulation.

'Every Possible Presumption'

On March 5, 1934, the Supreme Court declared New York shopkeeper Leo Nebbia to be an enemy of his state. Nebbia's crime? He sold two quarts of milk and a 5 cent loaf of bread for the combined low price of 18 cents, thereby violating the commands of New York's Milk Control Board, which had set the minimum milk price at 9 cents a quart in order to combat such "evils" as price cutting and "destructive competition."

This bears repeating. During the lean years of the Great Depression, the Supreme Court gave its blessing to a government-mandated price hike on milk. Why? "A state is free to adopt whatever economic policy may reasonably be deemed to promote public welfare, and to enforce that policy by legislation adapted to its purpose," declared Justice Owen Roberts' majority opinion in Nebbia v. New York. Never mind the fact that low-priced milk posed zero threat to the cash-strapped public. "The legislature is primarily the judge of the necessity of such an enactment," Roberts held, and "every possible presumption is in favor of its validity." Among the precedents cited by Roberts was the Court's anti-margarine ruling in Powell v. Pennsylvania.

Nebbia arrived at a turning point in American legal history. Before the mid-1930s, the Supreme Court sometimes—though not always—overruled economic regulations for exceeding the government's lawful reach and violating the constitutional rights of entrepreneurs, small business owners, and employees. In 1935, for example, the Court nullified the New Deal's National Industrial Recovery Act on the grounds that congressional power under the Commerce Clause did not allow federal officials to control the local sale and slaughter of kosher chickens in Brooklyn. "The country was in the horse-and-buggy age when that clause was written," fumed President Franklin Roosevelt in response.

But FDR got the last laugh three years later when the dairy lobby stepped up and delivered another sweeping win for the regulatory state. At issue in United States v. Carolene Products Co. was a federal statute known as the Filled Milk Act. Its purpose was to ban the interstate shipment of so-called filled milk, which is basically a dairy product made by adding vegetable oil to skim milk. True to form, the dairy industry took an immediate dislike to its latest low-cost competitor and lobbied intently for the federal restriction.

Writing for the Supreme Court in 1938, Justice Harlan Stone followed in the deferential footsteps of Powell and Nebbia. When it comes to "regulatory legislation affecting ordinary commercial transactions," Stone declared, "the existence of facts supporting the legislative judgment is to be presumed." Henceforth, Stone instructed, the federal courts must give lawmakers the benefit of the doubt in all cases dealing with the constitutionality of economic regulations. As for the purveyors of filled milk—a perfectly safe and healthy food product, by the way—their interstate enterprise was out of luck.

'The Economic Interests of a Powerful Faction'

Which brings us back to Hein Hettinga and his ill-fated attempt to bottle and sell low-priced milk in the early 21st century. In her concurrence in Hettinga v. United States, Judge Brown characterized the federal government's actions as a forced collectivization scheme that injured consumers and enriched special interests. Nonetheless, Brown reluctantly conceded that under the pro-government judicial deference mandated by Nebbia and Carolene Products, both of which she dutifully cited, she had no choice but to uphold the offensive regulation.

Those rotten precedents continue to wreak havoc in all manner of cases. In Chicago, food truck vendors are currently waging a legal fight to overturn their city's arbitrary street parking restrictions. In Florida, a beer store is seeking to void that state's nonsensical ban on selling freshly brewed suds in the popular 64-ounce containers known as "growlers." Thanks to the dairy lobby's legal triumphs, these small businesses (and countless others like them) enter the courtroom with the scales of justice already tipped heavily against them.

As Judge Brown aptly observed in Hettinga, "the government has thwarted the free market, and ultimately hurt consumers, to protect the economic interests of a powerful faction. Neither the legislators nor the lobbyists broke any positive laws to accomplish this result. It just seems like a crime." It sure does.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Spilled Milk."

Show Comments (22)