Governor Explains Why the Minnesota Sex Offender Program Is a Crock

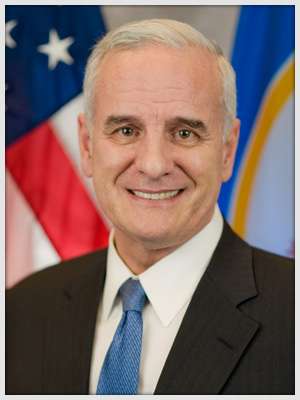

Defending the constitutionality of civil confinement, Mark Dayton exposes the fallacy at its core.

Last week U.S. District Judge Donovan Frank ruled that the Minnesota Sex Offender Program (MSOP), which civilly confines people after they have completed their criminal sentences, violates the 14th Amendment's Due Process Clause. Minnesota Gov. Mark Dayton disagrees, but his defense of the program exposes the fallacy at its core. "It's really impossible to predict whether or not [sex offenders] are at risk to reoffend," Dayton says. "So the more protection you can give to the public, as far as I'm concerned, given their history, is entirely warranted, and that's what this program does right now."

The problem with Dayton's position is that the law authorizing the MSOP requires predictions about whether or not sex offenders "are at risk to reoffend"; if such predictions are "impossible," the whole law is a crock. Under the Minnesota Civil Commitment and Treatment Act, two kinds of offenders can be locked up, ostensibly for "treatment," after they have served their time: a "sexually dangerous person" or a "sexual psychopathic personality." The former is defined as someone who "has engaged in a course of harmful sexual conduct"; "has manifested a sexual, personality, or other mental disorder or dysfunction"; and "as a result, is likely to engage in acts of harmful sexual conduct." The latter is defined as someone who is deemed to exhibit "such conditions of emotional instability, or impulsiveness of behavior, or lack of customary standards of good judgment, or failure to appreciate the consequences of personal acts, or a combination of any of these conditions, which render the person irresponsible for personal conduct with respect to sexual matters, if the person has evidenced, by a habitual course of misconduct in sexual matters, an utter lack of power to control the person's sexual impulses and, as a result, is dangerous to other persons." Crucial to both of these definitions is a finding that the person, because of his purported disorder, is likely to commit new crimes after being released. But according to Minnesota's governor, who claims there is nothing wrong with the MSOP, such findings are basically bullshit.

It gets worse. "I don't think any parent in Minnesota wants to subject their daughter or their son to a probability," Dayton says. "They want to make sure their government is doing absolutely everything conceivably possible to make it 100 percent safe to walk in the park or to or from school." So even if recidivism were predictable, Dayton would say that someone who is 99 percent guaranteed not to reoffend should nevertheless be locked up for the rest of his life. Just in case.

It is precisely this reluctance to release anyone, no matter how unlikely he is to commit new crimes, that persuaded Judge Frank the MSOP is a system of punishment and preventive detention disguised as psychiatric treatment. When no one is ever deemed well enough to be released, the pretense that the people confined by the MSOP are patients rather than prisoners is so obvious that even Dayton can't be bothered to carry on the charade.

[Thanks to Pope Jimbo for the tip.]

Show Comments (45)