How the 11th Circuit's 'Wooden Application of the Third-Party Doctrine' Threatens Privacy

The court's cellphone decision implies that remotely stored information has no Fourth Amendment protection.

As Scott Shackford noted earlier today, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit yesterday overturned a 2014 panel decision requiring a probable-cause warrant to obtain cellphone location records. Last year, in a case involving an armed robber named Quartavius Davis who was linked to the scenes of various crimes by cellphone data, a three-judge 11th Circuit panel concluded that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy in such information, which can reveal where you are throughout the day, every day. The full court disagreed, saying that claim is foreclosed by the Supreme Court's "third-party doctrine," which holds that "a person has no legitimate expectation of privacy in information he voluntarily turns over to third parties." The Court also has said "the Fourth Amendment does not prohibit the obtaining of information revealed to a third party and conveyed by him to Government authorities, even if the information is revealed on the assumption that it will be used only for a limited purpose and the confidence placed in the third party will not be betrayed."

Given the sweeping language of those precedents, you can see why the 11th Circuit ruled the way it did, joining two other circuits (the 5th and 6th) that have reached the same conclusion. The three judges who signed last year's decision and the two dissenters from yesterday's ruling tried to avoid that result by arguing that cellphone users do not voluntarily disclose their locations when they make and receive calls and may not even realize their service providers collect and store that information. Nonsense, says the full court:

Cell users know that they must transmit signals to cell towers within range, that the cell tower functions as the equipment that connects the calls, that users when making or receiving calls are necessarily conveying or exposing to their service provider their general location within that cell tower's range, and that cell phone companies make records of cell-tower usage. Users are aware that cell phones do not work when they are outside the range of the provider company's cell tower network. Indeed, the fact that Davis registered his cell phone under a fictitious alias tends to demonstrate his understanding that such cell tower location information is collected by MetroPCS and may be used to incriminate him.

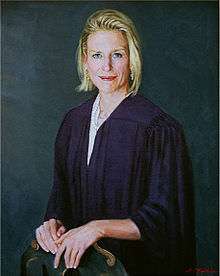

Then again, maybe not. As Judge Beverly Martin (who also joined last year's decision) notes in her dissent, statements by the prosecution in this case suggest that cellphone users do not necessarily realize they are carrying tracking devices. "What this defendant could not have known was that…his cell phone was tracking his every moment," a prosecutor said during Davis' trial. The government also observed that Davis and his accomplices "had no idea that by bringing their cell phones with them to these robberies they were allowing MetroPCS and now [the jury] to follow their movements."

Whether or not Davis recognized the privacy implications of carrying a cellphone, ignorance of that subject is a pretty thin reed on which to hang a warrant requirement, as I noted in a column last year. Once you understand how cellphones work, do you lose any Fourth Amendment interest in the information about your whereabouts revealed by the spy in your pocket? Under the 11th Circuit's reasoning, you do. Martin notes that the data obtained without a warrant in this case covered 67 days, during which "Mr. Davis made or received 5,803 phone calls, so the prosecution had 11,606 data points." But that is nothing, she says, compared to the warrantless data grabs that would be allowed by the court's "wooden application of the third-party doctrine":

Under a plain reading of the majority's rule, by allowing a third-party company access to our e-mail accounts, the websites we visit, and our search-engine history—all for legitimate business purposes—we give up any privacy interest in that information.

And why stop there? Nearly every website collects information about what we do when we visit. So now, under the majority's rule, the Fourth Amendment allows the government to know from YouTube.com what we watch, or Facebook.com what we post or whom we "friend," or Amazon.com what we buy, or Wikipedia.com what we research, or Match.com whom we date—all without a warrant. In fact, the government could ask "cloud"-based file-sharing services like Dropbox or Apple's iCloud for all the files we relinquish to their servers.

According to the third-party doctrine, such deeply personal and highly revealing information has only as much protection as legislators decide to give it. As Justice Sonia Sotomayor suggested in 2012, it is long past time for the Supreme Court to revisit this misbegotten principle, which was enunciated nearly four decades ago and becomes a bigger menace to our privacy every day.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

So many nut punches today you'd think Balko was visiting the Reason offices.

They really are working it like a speed bag today.

March 6th, 2015, the day of innumerable bruised grapes.

is that picture of the real judge? And is that reference to "wooden application" about the judge causing people to sport wood?

Skylar White is moving up in the world.

That painting reminds me of the Susan Ross Foundation from 'Seinfeld'.

It reminds me of the "Man Hands" episode of Seinfeld.

It reminded me of much older movies where the haunting portrait of a stern ancestor looms in the parlor, foreshadowing a dim future for any who meets its inscrutable gaze.

Obviously, if you don't want the police tracking your every move, you should stay home.

Or if you're going out to commit a crime leave your cell at home and then use the location data as an alibi.

Once you understand how cellphones work, do you lose any Fourth Amendment interest in the information about your whereabouts revealed by the spy in your pocket?

Under expectation of privacy analysis, it doesn't even matter if you have a personal expectation of privacy.

Only whether the judge believes you should be extended such an expectation of privacy.

Under their third-party doctrine, it doesn't even matter whether an expectation of privacy in information held by a third party is legitimate, anyway.

The amount of data scooped out of your mobile devices by various third parties is absolutely amazing. For awhile, Google (or maybe it was Apple), was actually harvesting the passwords on your device to any wifi router. That converted it to third-party info, and meant that even though you had a perfectly justifiable expectation that your secure wifi network was private, the cops could it from Goopple, get into your network, and go through all your shit. After all, you don't have an expectation of privacy against anyone who has your password, do you?

Bottom line: nothing connected to a network or the internet is protected by the 4A. Nothing. The Founders must be so proud.

That was Google, not Apple.

Yeah, I'm sticking with "Goopple" anyway.

And they were not grabbing passwords, they were grabbing whatever traffic was coming by. Buried in those logs were badly secured passwords and other stuff.

But the point remains, if you use a smart phone and surf the web, google and microsoft know everything about you. Where you go, what you buy, what you watch.

They even integrate your home experience with your internet experience. When I stream stuff on my home theater, google adds it to my google now experience, even though I am not getting the content from google and I never told google about it. Their net is massive.

It makes a great improvement to my internet experience, but it is also scarily invasive.

Must...resist...offensive...jokes....

Oh come on, that's an awesome name! Especially if he's the 8th child and 4th son.

Ot: is anyone else getting antigun ads on hitandrun today? lol talk about falling on deaf ears.

AdBlock + Firefox = no adds

So I have no idea.

Tradecraft, ladies and gentlemen. Learn to use it.

Agreed... but...

The same way me paying someone else to commit murder is still a crime and arguably as bad as murder, the government taxing me to use force to compel others to spy on me is as bad, if not worse (morally, legally, and economically), than if they had spied on me directly.

Moreover, my tech-fu will never be greater than all of the contractors on the payroll.

Tech fu is arguably what gets so many people in trouble. They think anonymity and security from the prying eyes of the state can be achieved with an app.

Going lower tech is in many ways, the first step to avoiding detection.

"a person has no legitimate expectation of privacy in information he voluntarily turns over to third parties."

I guess I don't get this.

There's a lot of ways to look at this.

If we take the word "voluntarily" literally, some of this data we don't "voluntarily" hand over. Unless we declare that use of a cell phone is voluntary, therefore all data emanating from the cell phone that the manufacturer explicitly or implicitly transmits to the carrier unbeknownst to the user is by extension, voluntary.

Also... why is information magically not private when I voluntarily turn it over to a 'third party'. For instance, when one goes to a priest for confession, or discusses things with a psychiatrist, that is information 'voluntarily turned over to a third party'. is that not private?

If I write a letter and send it through the post... that is information I have 'voluntarily turned over to a third party', the third party could be interpreted as the postal service OR the intended recipient.

So, for discussion, I need to fully understand the word "voluntarily" and the limits to the definition of "third party".

When I consult with my lawyer, that is information that I have voluntarily handed over to a third party. Is that conversation not privileged?

I didn't know the wife on Breaking Bad was a circuit court judge.

If I have a safety deposit box, do I lose my 4th Amendment rights because I have voluntarily given something to a third party? What about a storage locker I'm renting? What if a friend lets me use a file cabinet at his house that is locked (he can't access)? What if he can access it?

What about my lawyer or doctor?

Don't the police normally need a warrant for at least some of these situations? Why, when it comes to digital data, does the need for a warrant go right out the window?

The US Government has a history of taking stuff from safety deposit boxes.

Your doctor isn't smart enough to protect you, and probably doesn't give a shit anyway.

Your lawyer will protect you, as long as you pay your bill. If the police question your lawyer about you, your lawyer will probably bill you for his time even if he gave them no information.

This is great, the cops get this shit right away just by asking. Do you have any idea how much work it is for a defense attorney to try to get the same data? Probably $10,000.00 is conservative as to how much it would cost a client to get this stuff. You need to file a petition, get a judge to approve it after a hearing, then pay the telecom to provide copies of it. Want to authenticate it at trial? If the Prosecution won't stipulate to authenticity that's another $10k to fly somebody in from corporate headquarters to testify.

It's fucking ridiculous.

I'm as radical libertarian as it gets, folks -- in fact I am pretty much full on ancap -- and let me tell you: anything you fucking broadcast over the fucking aether or transmit through a line which you do not own has absolutely no rights basis for an expectation of privacy whatsoever, no matter how encrypted it is. All it may have, reasonably, is the HOPE of privacy.

that's nice from a technical POV, but from a legal one, sort of besides the point.

really? Because all I see here are a bunch of libertarian-claiming whiny bitches whining and bitching that the government is reading the email and location data that they send from their phones.

if you don't want the government knowing where you are at any given time, how about not walking around in public with a god damn radio transmitter in your pocket that is on at all times

all the so-called libertarians that are arguing that the government has no right to location data and other information, personal or not, transferred via cloud connected devices over the airwaves are not making a rational argument. They are instead engaged in what is called special pleading.

basing your positions on special pleading puts you in the same category of morons as the progtards

if you want to use the the wonderful power of modern day devices in order to make your life more convenient, you had better invest in good encryption -- and pray that it does not get cracked. but do not invent spurious new rights such as electronic privacy just because you are too lazy to do so.

make no mistake - your privacy is guarded only by your vigilance

Hello, Cloud Computing!

Always use a VPN.

Burners, people. Burners.

And change vendors, every couple years at most. Your loved ones won't mind, your not-so-loved ones will be the people complaining about your frequent phone number-switching.

What counts as a "call" in this context? 5803 calls in 67 days means an average of 86.6 calls a day. Did he really make that many voice calls every day, or does it include data or other kinds of background operations? If it includes background data transfers for an app, should the user realize that this substantially increases the amount of tracking information that gets saved?

Overall, how sophisticated are users supposed to be about the details of mobile phone operations? How does the network determine where to send a notification that number 888-555-1212 is being called -- does it send it just to one tower, or to all the towers in a particular area? If it sends that notification to/from all towers in some area, should a user expect that the precise tower their phone used gets saved (assuming they don't make outbound calls)?

Frankly, it sounds like tech-savvy LEOs (and maybe prosecutors) are misleading courts -- that they imply that mobile networks need the exact information that is being saved to function properly, whereas they only use some of those details. Have any mobile network (equipment or operations) engineers testified as to what "call" means in this context, or whether exact tower information needs to be saved to make all these calls work?

"What this defendant could not have known was that...his cell phone was tracking his every moment," a prosecutor said during Davis' trial."...

... also implies that the defendant has never watched a TV program where that happens in nearly every episode... sorry about that... ignorance of the law isn't an excuse, but neither should be stupidity!