National Review Launches Another Attack on 'Libertarian Constitutionalism'

The conservative magazine doubles down on its defense of judicial deference.

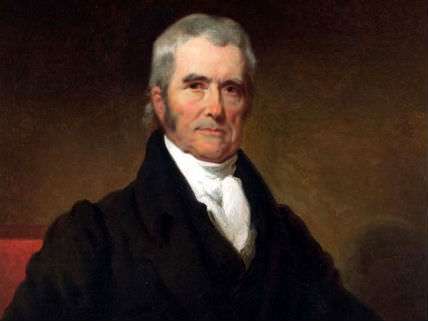

Last week I debated two writers from the conservative magazine National Review about several of the historical arguments made in my new book Overruled: The Long War for Control of the U.S. Supreme Court. In brief, National Review's Carson Holloway and Ramesh Ponnuru each asserted that my book's "libertarian constitutionalism" fails because it is at odds with the views of the founding fathers. According to National Review, the founding fathers consistently embraced the philosophy of judicial deference, which says that the courts should rarely—if ever—strike down statutes enacted by the democratically accountable branches of government. "John Marshall—the most consequential chief justice in the nation's history—was a proponent of judicial restraint," National Review declared.

What's the evidence for that assertion? "In Fletcher v. Peck (1810), Marshall held that judges should 'seldom if ever' declare a law unconstitutional 'in a doubtful case,'" National Review wrote. This week, National Review doubled down on that assertion.

So what's the truth of the matter? To be sure, John Marshall did make a nod in the direction of judicial restraint in Fletcher v. Peck. But guess what else Marshall did in that case? He ruled the actions of a state government to be unconstitutional. In fact, Fletcher v. Peck is one of the first cases in American history where the U.S. Supreme Court overruled a state legislature on constitutional grounds. Not exactly a shining beacon of judicial deference. To put it plainly, it's a real stretch to try and transform John Marshall—of all founding era figures—into the poster boy for judicial minimalism.

A second point of dispute between me and National Review is nicely captured in this statement by one of my two conservative opponents: "Root argues that judicial restraint, though many conservatives have championed it for decades, actually has progressive roots. I take it that this argument is meant to suggest that conservatives should be suspicious of the idea."

My book is primarily a work of legal history and my object was to understand and explain how the longstanding debate over the merits of judicial deference has shaped American law. And on this point the historical record is crystal clear: Progressive legal theorists and fellow travelers such as Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., James Bradley Thayer, Felix Frankfurter, Learned Hand, Hugo Black, and Alexander Bickel had an overwhelming and decisive influence on modern conservative advocates of judicial deference, such as the late Robert Bork. Indeed, as I previously noted, Bork himself openly and proudly credited the Progressives for their definitive influence upon him. In Bork's own telling, today's legal conservatism has firm Progressive roots.

Does that mean National Review should now be suspicious of Bork? Perhaps it should. After all, Bork certainly would have rejected National Review's dubious attempt to enlist John Marshall in the cause of judicial deference. According to Bork's 1991 bestseller, The Tempting of America, Marshall was "an activist judge" in many regards, including when it came to Marshall's "remarkable performance" (not a compliment) in none other than Fletcher v. Peck, in which Marshall "had to go well out of his way to float the idea that a court might strike down a statute even where 'the constitution is silent.'"

One final point. National Review's Carson Holloway wrote this week that nothing I've argued "proves that judicial deference is something progressives invented for progressive purposes."

But I never made that silly claim in my book (or anywhere else). Indeed, my book's first chapter chronicles the bitter debate over judicial deference which occurred in the aftermath of the Civil War and the ratification of the 14th Amendment—a period of history which clearly falls several decades before the Progressive movement came along.

My central point in this whole brouhaha with National Review is that today's legal conservatives owe a vast intellectual debt to the Progressive case for judicial deference, and that those same legal conservatives do not owe such a debt to founding fathers like John Marshall. What's more, today's legal conservatives routinely invoke Progressive (and New Deal) legal theories as justification for their own deferential judicial stances in a range of cases. And at the risk of repeating myself, let me just add that Robert Bork, the most influential conservative legal theorist of the past half century, agrees with me on all of that.

In other words, if the folks at National Review are so bothered by the Progressive roots of Borkian legal conservatism, their beef is with Bork himself, not with the uncomfortable historical evidence contained in my book.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Deference to the whims of the legislature is what kept Obamacare alive. That's what these conservatives are pining for?

Now that Congress is controlled by Team RED.

You know what's great about being libertarian? You get it from both ends... at the same time.

Maybe that's why there are no libertarian women.

I thought that was what's great about being Lisa Ann.

Lucky Pierre-Joseph Proudhon!

(Yeah, I'd never heard of him either. The list of libertarian writers named Pierre is not very long.)

Well then. Fuck that guy.

--Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

--Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

--Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

And yes, I know it's embarrassing that I'd never heard of this guy. Fucking worthless engineering degrees...

Mises has a chapter on Proudhon and Syndicalism in his book Socialism. Which he goes into all the fallacies with Proudhon's mutualism. Definitely worth a read if you ever have to debate anarcho-syndicalists.

We could call it...the Chinese Finger Trap Party.

I don't understand this given that, in practice, National Review always agrees with you. NR favored the decisions striking down gun bans, correct, including Heller? And they want Obamacare to be struck down, right?

So they're basically arguing with you based on alleged principles which the National Review set don't even appear to adhere to.

What was NRO's position on stuff like power of the executive during Bush II's term?

I think for a long time it was part and parcel to their "we are the standard-bearers of federalism" claim. That's all well and good if states are 100% of the time acting as the breaks on a runaway federal government. But as you point out, in DC and Illinois that certainly wasn't the case when it came to the 2nd Amendment and the court struck down those district/state laws. You would think they would understand that a strong court saying "no, no, FUCK NO" to laws, whether they be state OR federal, would be a good thing if you actually hold true to the "conservative" principle of a small government of limited powers. Therein lies the rub. They really just choose to hold that principle when it's convenient to strike down things they don't like but conveniently forget it when trying to shove something of their own making down our throats.

I suppose it wouldn't do any good to point out, once again, that the problem isn't really restraint vs activism. Activist judges have also invented new positive rights from whole cloth and effectively ruled by judicial fiat. What is needed is a judicial doctrine of honesty and impartiality.

Completely agree. Without devolving completely into relativism here, the problem still always begins with differing theories of interpretation. Where I think a combination of textualism/originalism is the appropriate starting point, clearly others disagree. Whether a court is "activist" or "deferential" is a canard to the (my) real question of "does it comport with the meaning, understanding and intent of the relevant section of the Constitution at the time in which it was adopted?"

What you really need is judges who can read.

That would help too.

Also, it seems to me that judicial deference should mean deferring to the most important law of the land - the Constitution. Therefore, the claim by conservatives that 'deference' means deferring to the legislature seems to me completely absurd because if the legislature oversteps the bounds of their Constitutional mandate it is the court's job to strike down any laws which fail to defer to powers granted by the Constitution.

If anything, Root misnamed his own legal theory. This isn't 'libertarian activism,' it's simply deference to the actual documents on which our country was founded rather than the transitory will of the mob. How can conservatives claim to care about the Constitution while supporting a legal theory that actively allows the Constitution to be superseded by whatever the legislature happened to be thinking last Friday?

Because at this time, the legislature last Friday was controlled by their team.

I prefer to call in Constitutional Constitutionalism. Apply and enforce the Constitution as written.

The judicial power to strike down laws that violate the Constitution arises from this statement:

This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof; . . . shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the constitution or laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding.

Statutes must be made "in pursuance" of the Constitution. Statutes that are not Constitutional are void. How do you enforce this, if not with the courts? How do you say it can't be enforced without saying its meaningless?

shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the constitution or laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding.

So... that whole "it doesn't apply to the states" thing?

I would rather have it enforced by state nullification. The alternative is to let one part of the federal government decide what the powers of the federal government are.

This modern fedgov would prolly interpret nullification as rebellion and use it as an excuse to place the offending state under martial law...

the courts should rarely?if ever?strike down statutes enacted by the democratically accountable branches of government

IOW, the Constitution isn't really a law that the courts may enforce against legislatures. I mean, once you say the Courts can't strike down legislation, isn't that what you are saying?

So what's the point of all that garble in the Constitution about limits on government power, enumerated powers, etc. etc. What's the difference between no law (or no Constitution), and one that cannot be enforced?

Let's take the extreme example: Congress prohibits any publication of criticism of a member of Congress. Can the Court strike that statute? If they can strike that statute down, then why not one authorizing the NSA to wiretap every single computer and phone in the country (or whatever it is that NR believes Congress should be able to do, Constitution be damned)?

So what's the point of all that garble in the Constitution about limits on government power, enumerated powers, etc. etc.

The whole thing is based on protecting individual liberty from mob rule. The only reason NR is doing this shit... I'm guessing... is because they think they have a real shot at the white house so they're warming the Executive Power seat.

Exactly. You would think NR would also have the intellectual honesty to refer to the fear of the vast majority of the Founder's as it pertained to unchecked democracy.

This is exactly right. The answer is that they are more afraid of losing legislation they like than they are about having to deal with legislation they don't like.

They'd rather have The Patriot Act and all that the security state entails and Obamacare, than risk losing both Obamacare AND their own sacred cows.

NO RC. You misquoted the case. You forgot the clause "in a doubtful case". That is not saying the Constitution shouldn't be enforced. And you are right, it is a law. Do you want ever law strictly enforced even in doubtful cases? Do you think doing so with criminal laws would be a good idea? If not, than what is so special about the Constitution?

I didn't quote a case at all, John.

As for deference, why does one co-equal branch owe another co-equal branch any deference at all?

The "doubtful" case is a red herring. What is that supposed to mean? I think it probably goes to the level of "proof" needed. As it is, we seem to have a "beyond reasonable doubt" standard for striking down a statute. Why not a "preponderance" standard? Its a civil case, after all.

So, if you can't meet the preponderance standard, its a doubtful case - you haven't carried your burden.

See? No deference needed, no new standards of review.

As for deference, why does one co-equal branch owe another co-equal branch any deference at all?

Because it is an equal branch and passing laws is its job. If the courts don't owe the legislatures any deference such that they strict down any law for which there is any doubt about its constitutionality, why then shouldn't legislatures treats courts the same way? If you are going to argue that courts owe legislatures no deference, it seems to me that legislatures owe courts none either. That means legislatures and executives are free to take the most restricting interpretation of any court ruling and ignore any court ruling for which it thinks there is some doubt as to its validity.

I seriously doubt you or Root would support that. Yet, it would be doing nothing but applying an equal standard to both branches. Ultimately, this whole thing comes down to Root and the people on this board loving judges and distrusting legislatures. I certainly don't trust legislatures either. Why you people think judges are any better and worthy of a special place in the three branches is beyond me.

I think it's not about trusting judges but about trusting the long established provisions of our written constitution.

No its not. There is nothing in the Constitution that says the courts should shrike down any law for which there is any doubt about its constitutionality. Indeed, there is nothing that says the courts even get the final say in what the Constitution says. That practice came later after Marbury.

The Constitution is the supreme law of the land. If the judiciary, whose function is to interpret and apply law shouldn't get that task with it then who?

If the judiciary, whose function is to interpret and apply law shouldn't get that task with it then who?

The other two branches. Nothing in the Constitution says they get the final say. Indeed, Congress has the power to restrict the jurisdiction of the courts such that they could if they choose to deprive the courts of the power to hear certain cases. You can't reconcile that power with the idea that the Constitution intended the Courts to have the final say as to its meaning.

Nothing in the Constitution says they get the final say.

Nothing in the Constitution says any branch gets the final say.

If somebody gets the final say (and I think somebody should), then why not the courts? They seem better suited than either of the other two.

If somebody gets the final say (and I think somebody should), then why not the courts? They seem better suited than either of the other two.

Because they are not elected. And the document clearly intended Congress to be the most powerful and primary branch. If courts were supposed to be this powerful, why does Congress and only Congress have the power of impeachment?

You and Root's only argument is that you like judges. Well, I don't.

But John, by your own admission Congress has tools at its disposal to put a runaway judiciary in check, if it believes such. Just because Congress hasn't restricted jurisdiction and I believe has only impeached 15 federal judges in over 200 years doesn't mean that the supreme judicial body isn't tasked with being the final arbiter of legal disputes.

Catafish,

They have that power to fix the system when it is not functioning. That power tells you how the system should function. It should function with Congress getting some deference. The system wasn't designed for the normal state of affairs to be the Courts defying Congress and Congress impeaching them. That is the exception. The normal state is for the courts not to give Congress a reason to impeach them.

John, every Member of Congress swears an oath to defend and uphold the Constitution, do they not? Setting aside the issue of whether that's worth the air required of them to utter, who holds them to this? If you feel it's simply the electorate, do I understand you correctly to believe that the federal judiciary holds absolutely ZERO role in the review of the constitutionality of legislation?

Sure they do. Why do you assume that every law is tyranny and every judge acting within the Constitution? Congress gets a say in what the Constitution means just as much as the Courts do. You want to take that power away and make the Constitution mean whatever judges decide it means.

Understand what Root is claiming here. He is saying that if there are two reasonable ways of looking at the law, the court should strike the law down. That sounds nice until you realize what is reasonable for the judge is usually going to come down to that judge's politics. So Root is just saying judges should strike down any law they think is unconstitutional. The fact that there is a reasonable argument that it is and that the voters and the other two branches find that argument compelling, doesn't matter. All that matters is what the judge finds compelling. That is judicial tyranny.

The Court can declare laws unconstitutional and therefore void. If Congress disagrees with the Court's interpretation, they can propose an amendment to the Constitution to impose their view.

That's not tyranny. That's an elegant system of checks and balances. It doesn't require deference on anyone's part, and, since the Court can only void laws, and Congress needs a supermajority to overturn their decision, it's weighted toward liberty.

I'm not sure why you're so vehemently opposed to it, John. I'd hypothesize that, as a lawyer, you've developed a healthy contempt for judges. But aren't legislators just as contemptible?

The Court can declare laws unconstitutional and therefore void. If Congress disagrees with the Court's interpretation, they can propose an amendment to the Constitution to impose their view.

Sure they can. But that is very difficult to do. Lets say you have a law that is supported by 60% of the voters and by extension 60% of the Congress and the President. Under Root's view if a judge can find any argument that it is unconstitutional, that judge should strike down the law. So the word of one judge and 40% of the public outweighs 60% of the public, Congress and the Presidency. And that is not tyranny?

I am not saying the courts shouldn't strike down laws. They certainly should. But they should strike down laws when they are clearly unconstitutional. Root wants them struck down anytime anyone can think of any reason they are. In practice Root wants to tell judges they should strike down any law they don't like or if they read it strictly, any law that anyone can claim is unconstitutional for anything but the most baseless reason. That is not how the system was intended to work and is certainly not how a Republic should work.

It is Root who is buying into the Prog judicial tradition here. He wants a results based judiciary willing to buy any argument necessary to overturn laws Root doesn't like.

So the word of one judge and 40% of the public outweighs 60% of the public, Congress and the Presidency. And that is not tyranny?

It's not majoritarian, but whether or not it is tyranny depends on the specifics of the case and whether or not it ends with the government being allowed to, or somehow forced to, violate its citizens' rights. It seems to be far more difficult for the judiciary to force the other branches to act than to prevent them from acting. That makes it difficult for the Court to impose tyranny that the legislature and executive aren't willing to engage in. Which makes them a good candidate for final arbiter of constitutionality. Especially since the other branches have control over who ends up on the Court, and have the ability, admittedly with difficulty, to undo their decisions if they outrageously abuse their power.

Argumentum ad populum

We are a Republic not a Democracy. A primary purpose of the Constitution was to prevent the 50+% from imposing upon the minority.

Here is where I think we are coming to an understanding of each other's positions. I agree with Root's position (or at least your characterization of it...I have not read his book yet) that, if there is a reasonable argument for or against a law's constitutionality, it should be found unconstitutional. I agree with you that the outcome of such a system is 100% predicated on the interpretive ideology of the judge. My support of Root's position is predicated on that judge's interpretive ideology being honestly and faithfully interpreting the Constitutional provision in a manner that is consistent with its meaning and intent at the time it was written.

I will grant that there are at least four justices and a current president who think that last sentence amounts to "politics." I equate it to being "correct."

Catafish,

It comes down to who do you trust more, judges or Congress. As much as I dislike Congress, I trust them more than judges. Congress is subject to election and judges are not. Judges tend to buy into the worst sorts of tyrannical ideology and be the least trustworthy with power.

History has shown that elections are hardly a check on Congressional overreach and is generally meaningless.

With the two-party control of the election process, especially who can get on the ballot and drawing/gerrymandering Congressional districts, it is extremely rare to unseat an incumbent as "punishment" for bad legislation. Furthermore, it happens after the fact, so the bad legislation -- the overreach -- is not corrected by removing those responsible for enacting it.

Furthermore, far too often the overreach is... ahem... popular; it appeals to the majority's whims or desires. Consequently, it is more likely to be rewarded at the ballot box than punished, in large part because the majority of the electoral participants are ignorant of, apathetic, or downright antagonistic to the limits that the Constitution is intended to impose on the Government.

But the judiciary has the least teeth. It has no real power to enforce, beyond a Gentleman's Agreement with the other Branches, its rulings.

As opposed to Congress deciding what it means with regard to their powers and authorities, rendering it meaningless...

The Constitution, as intended, defines the scope of Congress' power, delegating specific authorities and prescribing certain limitations. If you surrender to Congress the authority to adjudicate the definitions of those authorities and limits, then the Constitution is utterly meaningless as Congress will(has) declared their legislative authority to extend far beyond the scope of Article II, Section 8 (e.g. contorting the "General Welfare" and "Commerce Clauses") and their limits to be less (e.g. Assett Forfeiture).

The fact that they face elections (while Judges do not) is utterly irrelevant. Incumbents are rarely punished at the ballot box for overstepping their proper Constitutional limits. Indeed, they are generally rewarded as those transgressions appeal to the majority of the electoral participants (who are generally ignorant of, or apathetic or downright antagonistic to, the Constitution and the expressed limits on the Government's power).

Intentional or not, that is a blatant falsehood.

Article III, Section 2:"... In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make." (emphasis added)

Additionally, Article VI: "... This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding..." (emphasis added)

[continued]

[continued from above]

Pursuant to Article III, Section 2, the Supreme Court has the delegated power to adjudicate the Law as well as facts. Pursuant to Article VI, the Constitution is Law. Therefore, the Supreme Court has the delegated power to adjudicate the Constitution as well.

Marbury v. Madison did not usurp or otherwise invent that authority. It affirmed it. Furthermore, the decision makes a flawless argument that any law that is not "repugnant" to the Constitution cannot, in fact, be Law; never really was law; has no authority of law; and, therefore, is void.

But the legislature does just that. It is responsible for appointment of all federal judges and owes the Courts no deference in selection of said judges. Who the Court wants in the Court don't mean shit.

That has nothing to do with how much deference they give judges once they are appointed. In fact, your point argues for the courts giving deference to legislatures. The Congress is the primary branch of government from which all other branches are subject. Congress has the power to impeach the members of the other branches. So if there is any branch that was intended to be first among equals, it was the Congress. Root and RC just want the courts to be first because they love tyranny if it comes in wearing a black robe.

"Because it is an equal branch and passing laws is its job. If the courts don't owe the legislatures any deference such that they strict down any law for which there is any doubt about its constitutionality, why then shouldn't legislatures treats courts the same way?"

He didn't say they could strike down 'any law for which there is any doubt,' he said they should change to a preponderance of the evidence standard. That's a completely different standard than striking down anything for which there is doubt.

So what? Why should thy do that? The Congress is the first branch of government. It has the power of impeachment. Why shouldn't the courts be weary of striking down enacted law?

Because if an enacted law contradicts the Constitution it should be struck down. I have a difficult time understanding why you don't think laws should be struck down when they're in conflict with the Constitution given that the Constitution is utterly meaningless if it can just be ignored at Congressional leisure.

I also like that you refer to people who agree with Root as 'Root's fans.' I don't give a shit about Damon Root, I just think that the Constitution must be the final law and if you don't allow laws to be stricken when they conflict with the Constitution, then the Constitution is simply dead letter that we periodically gesture towards and speak about in hushed tones when we're feeling smug about our history.

Sure it should. You are just begging the question which is what does it mean to contradict the Constitution and who gets the final say on what the document means.

And I am not saying laws shouldn't be struck down if they violate the Constitution. They clearly should. The issue is what exactly does it mean for a law to do that. My answer is that a law violates the Constitution when it clearly does, not when some judge thinks it probably does.

My answer is that a law violates the Constitution when it clearly does, not when some judge thinks it probably does.

So we're back to arguing the standard of proof. You seem to be going with a "beyond reasonable doubt" standard. I don't think that's a good standard here. For one thing, it was developed to protect people from the government, not to protect the government from the people.

Why not "preponderance"? If a judge decides its more probably than not that a statute violates the Constitution, why isn't that good enough? Isn't that more in line with the purpose of the Constitution, which is to limit government?

I don't think an evidentary standard is even applicable here. Either the law does or it doesn't. What the hell does a "preponderance" even mean when applied in this context? Does the regulation of personal wheat consumption violate the powers in the Commerce clause by a preponderance? That question doesn't even make any sense.

The answer is either it does or does not. And if there is a reasonable argument that the law doesn't, I don't see how a court can strike it down.

"The answer is either it does or does not. And if there is a reasonable argument that the law doesn't, i don't see how a court can strike it down."

I personally think it's more appropriate to turn your standard on it's head. In a system of specific, enumerated powers to the government, if there is any reasonable argument to support that it violates the Constitution, it should be struck down.

Carafish,

A lot of liberal judges who did things like forced busing and struck down state laws that conflicted with federal ones would agree with you.

They also previously engaged in the creation of "rights" out of whole cloth, something I disagree with entirely. Forcing government, state or federal, to walk into court and defend their law against the presumption of unconstitutionality is a good thing on the whole. I wrote above thread about the root problem still being one of interpretative theory.

I agree with you catafish. The problem was their view of the Constitution not their willingness to strike down laws. That is why Root isn't advancing the cause of limited government with his philosophy. A court being more willing to strike down laws isn't necessarily a good thing. It could be a very bad thing if the court has a bad view of the Constitution.

^Agreed^

Holy shit. Sorry. I'm new here, and usually enjoy the heck out of these debates. My eyes were glazing over here and then bam. It's over.

True; it either is or is not Constitutional.

And if there is a reasonable argument that the law isn't, I don't see how a court cannot / should not strike it down. Deference ought to be to the Constitution. It is less egregious to error on the side of the Constitution than the side of the legislation.

If a law is not clearly Constitutional, it should be struck, and the Legislature may choose to restructure and pass it again in a form that is clearly Constitution.

My central point in this whole brouhaha with National Review is that today's legal conservatives owe a vast intellectual debt to the Progressive case for judicial deference,

And that is in my opinion idiotic. "Deference" is in the eye of the beholder. If Root likes a law and it conforms with his idea of the Constitution, then I can guarantee you he will be all for judicial deference to the legislature. You can't talk about "deference" as some fixed term that exists outside of the circumstances.

The original Progressive view of the Constitution concerned the scope of federal power more than anything. The FDR Progressives thought that instead of the constitution being presumed to prohibit the federal government from doing anything the document didn't specifically authorize that instead it authorized the federal government to do anything it liked except that which was prohibited.

The Conservative concept of "deference" arose under entirely different circumstances. It was in response to courts invalidating laws and enforcing policies in the name of protecting rights. The conservative argument was at heart never about the scope of federal power but about the scope of judicial power. You just can't compare the two cases.

To put it in simple terms, the Progressives were saying the courts should stay out of the way while the Federal Government set off to solve the world's problems while the Conservatives were saying the Courts ought to stop overturning laws and dictating policies in an effort to solve the world's problems. The two ideas are different. Root seems to be claiming they are the same for the simple reason that he is the one who is looking to the progressive judicial tradition and wants no one to notice. The Progressive legal tradition was in addition to expanding federal power also a commitment to results based jurisprudence where the courts also became an instrument of Progressive change. Root's "libertarian philosophy" is no different. Root wants a results based jurisprudence, he just thinks hie desired results are better than the Progressive ones.

This. Activist judges have found that people have a "right" to a state education and welfare. They've found employment standards of all types to be illegal. They've forced states to raise taxes, and dictated the terms of schooling.

More latitude to strike down laws merely gives them more power to make laws. As imperfect as elections are it at least represents a potential check on power. What's the check on the SC? A tall tree and a short rope?

Thank you. That is what I have been trying to convince people for about 20 threads on this subject. Root and his supporters on this board just can't seem to grasp the idea that judges can be activist by striking down laws just as easily as they can by letting them stand.

Forced redistricting, forced new elections, forced State Senate Restructuring....

Impeachment and selecting new judges who aren't dictatorial. Why is this hard?

Because it never happens. Moreover, since judges can be impeached, doesn't that argue for more not less deference to Congress? Congress is effectively their boss and are their boss by design.

I guess this whole co-equal thing is hard for you? They are supposed to be in constant conflict. That's the basis of the system is to create three distinct power bases spending more time fighting with each other than oppressing people. It doesn't work if they all divide up the power and defer to each other. That's how we got from the 16-20th Amendments a century ago to this fight. Deferring to each other. Judges deferring to the legislature, legislators deferring their power to Federal agencies allowed to make their own rules.

I guess that whole reading comprehension thing is hard for you Brett? Those of us who can read have read the Constitution and understand that the branches are not co-equal. Congress is by design the primary branch.

Congress is listed in Article one and given all legislative powers. The courts are not listed until Article III. And Congress has the power of impeachment. Neither the President nor the courts have that power. Congress can remove the President or any judge. Judges or the President can't remove anyone in Congress. Congress is the primary branch and the branch the other two owe some deference to.

John, unless there is an "order of precedence" clause in the Constitution I'm unaware of, the number and ordering of Articles I, II and III doesn't mean squat. Under your analysis applied to the Bill of Rights, the First Amendment trumps the Second.

While I'll cede that certain powers - of which you accurately point out impeachment is one - are distinct to certain branches (and Congress certainly has more, the purse being a another big one), that does not mean that institutionally one branch is to be deferred to without question.

that does not mean that institutionally one branch is to be deferred to without question.

I am not saying it does. Understand that Root and RC are saying that the courts are the primary and most powerful branch of government. In their view the fact that the Congress thinks a law is constitutional and has a reasonable argument for it being so, means nothing. All that matters is the court's view and if the court doesn't agree, the Congress loses.

You don't have to agree with the Congress being firstt. Disagreeing with hat, however, doesn't mean the Courts are first. And that is what Root and RC are claiming.

I guess I don't see Root and RC as operating under that general premise. While I believe the judiciary has the final say on whether legislation is constitutional as written or as executed, they also can't author their own bills (although I'll grant the Court does seem to want to make a liar out of me there), can't raise monies to keep their own lights on, can't impeach or prosecute, etc.

I think I'm just on the same wagon with Brett that the Founders wanted to make it as difficult as possible to pass ANY legislation that would threaten individual rights, whether by overzealous politicians or an overzealous majority of the population, hence the tripartite system. I am 100% in agreement with you that - when coupled with an interpretative ideology that allows the words of the Constitution to be relative to time, space, gravitational distortion or whatever someone wearing black ate for breakfast that morning - judicial "activism" can also have disastrous consequences.

They may have intended that with regards to federal legislation, but they sure as hell didn't intend to have the federal courts meddling with the states. And that has what has happened. And Root's ideas would only make things worse at the state level.

I would argue that the Supremacy Clause declares otherwise, at least within a narrow scope.

Article VI, second clause: "This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding." (emphasis added)

As long as a State Law or Constitutional provision violates "the Supreme Law of the Land," the Federal Judiciary is, indeed, tasked with the appellate jurisdiction to meddle with the States.

More latitude to strike down laws merely gives them more power to make laws.

Were those cases establishing positive rights cases in which statutes were being struck down? Serious question.

Yes they were. They struck down laws that said you could get kicked out of government housing if you were a bad tenant. They struck down laws that said students should go to the school nearest their homes. They struck down laws that said property taxes were set at a given rate and should be used for the schools in their area.

Come on RC, do you not know there was a decade known as the 70s?

Since judicial review is no more than an implied power in the Constitution, it will never, and can never, be fully and finally defined. This lack of clarity itself gives a great deal of power to the federal courts, since they can be whatever a 5-4 majority on the S.Ct. thinks they ought to be at any given time, up to the limit that would cause a rebellion in the form of a successful constitutional amendment to limit their power.

Clarity in either direction would be helpful:

--The English/British system has survived and thrived for centuries despite lacking judicial review or even an independent judiciary.

--The Founders believed that the Article I and II would check each other and that each branch was responsible for complying with the Constitution. They also believed that the states would serve as a check on the feds. The Civil War removed the states from that equation, and the prosperity and bureaucratic nature of modern times has created a docile population no longer willing to question the federal behemoth. Because of this, the judiciary is probably a more important check and balance than it was at the time of the founding.

There is certainly some truth to that. It is also the case the the courts are now more of an instrument of federal power. The courts have over the last 50 years routinely struck down state law efforts to fight the federal government. Again, Root ignores the possibility that courts striking down laws can often be just as activist as allowing them to stand. It all depends on what law you are talking about.

Absolutely. Going even further, the courts are much less willing to strike down federal legislation, and the "political question" doctrine has greatly limited the degree to which the federal courts are willing to intervene as a 'referee' between the Article I and II branches.

If the states are ever to act as a check on federal power again, they will have to do so in an extra-legal fashion. In the not-so-distant future, I believe states on the political outs with DC will simply start to ignore federal laws they disagree with. The question will then become whether the federal government is willing or able anymore to enforce its will through force of arms. Unless things change direction drastically, I don't see our federal government being willing to do that.

That is sadly not a bad prediction. And it also points out another thing Root ignores. In the context of state power, Courts use the power to strike down laws as a form of judicial activism almost exclusively. Sure, striking down a federal law usually though not always will limit the power of Congress. Striking down a state law, however, usually means limiting the power of the states and by necessity increasing the power of the federal government, the exact opposite of what Root claims.

In the not-so-distant future, I believe states on the political outs with DC will simply start to ignore federal laws they disagree with.

Doesn't legalization of Marijuana in both Colorado and Washington not do exactly this?

The question will then become whether the federal government is willing or able anymore to enforce its will through force of arms.

So far so good. So the question might be that it probably depends on what the law is.

We know that slavery was one such concept that led to a force of arms.

The 17th Amendment didn't help much either.

or even an independent judiciary.

?

Act of Settlement 1701:

Judges' commissions are valid quamdiu se bene gesserint (during good behaviour) and if they do not behave themselves, they can be removed only by both Houses of Parliament, or the one House of Parliament, depending on the legislature's structure.

That's not an independent judiciary. They are subject to legislative removal if they do not "behave themselves."

So are American judges.

Only with a supermajority, Winston. That makes it effectively impossible absent extraordinary circumstances.

You do know that British Parliament has only removed one judge while the Senate has removed 9?

Sorry *8*

Not to mention that "good behavior" in the US constitution is a direct reference to the Act of Settlement.

Fair enough to all those points, but the important part of what I wrote is that the British courts lack the power of judicial review. There is check at all on the power of Parliament, save that of party politics and the pull of tradition.

If you say the judiciary isn't independent because judges can be removed by Congress, I guess you have to say the same about the executive branch, because the President can also be removed by Congress.

And you would be right. Who said the President was independent?

They were independent since the King couldn't remove them.

Winston makes a good point. The courts are not independent of a determined judiciary. All of the power ultimately lies in Congress since it can impeach the entire federal judiciary if it chooses to do so.

That cuts against your argument, doesn't it? No reason to defer to the legislature when it ultimately holds that power

No it goes the other way. Congress holds the power and therefore gets the benefit of the doubt. Courts are answerable to Congress therefore give it deference because it is designated as first amongst the branches in the Constitution.

Congress holds the power and therefore gets the benefit of the doubt.

To me, under a system designed to limit that power, it means just the opposite.

The system isn't designed to limit that power. The other two branches are powerless against a united Congress.

If that is the case, why do you argue for de-fanging the SC when Congress can certainly do that at the time it becomes necessary?

Because Congress shouldn't have to do that. Congress only impeaches the Supreme Court when the system breaks down. The system therefore is intended to give Congress some amount of deference. Impeachment is the exception not something Congress is expected to do as part of the system running properly.

The system is already broken. Congress and the Executive have already far exceeded their mandate and allotted powers as defined by the Constitution, at least by any reading that doesn't give the general welfare and commerce clauses supremacy over everything else.

I think in your efforts to prevent a Constitutional crisis between the branches, you're ignoring the Constitutional crisis that already exists.

Sure nerfherder, but the courts are broken too. Federal judges have run all over the states and done all kinds of harm to our system of federalism. And encouraging them to strike down more laws is only going to make things worse.

So how do you suggest we bring the tension back that rebalances the system? I just see a disdain for judges (which I understand) but I don't see how you propose to start rolling the damage back in.

You bring the system back in order via elections. You elect a Congress and a President that respects the Constitution and expects the courts to do the same. Depending on judges to do it for you is a fools errand. First, they likely are not going to do it since giving a single person that kind of power will always corrupt them. Second, winning via judicial mandate does not give the results anywhere near the legitimacy and permanency of wining elections.

Suppose we got all nine of the Supreme Court Justice to adopt the Lockner view of the Commerce Clause and a restrictive view of federal power such that they were philosopher kinds who invalidated about 90% of the federal government. That would be a Pyrrhic victory that would do nothing but cause the public to turn on the courts and turn to tyranny.

The English/British system has survived and thrived for centuries

Its hard for me to accept the idea that the British system hasn't completely failed to protect the rights of the people.

That too. The First and Second have prevented the USG from encroaching too much on guns and speech, at least until the progs get five votes.

When a court finds a state or federal statute to be incompatible with a provision of the Constitution and strikes the statute it is deferring to majority rules-every provision of the Constitution was adopted via a super majoritarian process.

"What's the evidence for that assertion? "In Fletcher v. Peck (1810), Marshall held that judges should 'seldom if ever' declare a law unconstitutional 'in a doubtful case,'" National Review wrote"

Whats' with all the focus on John Marshall anyway?

The most signifcant founding father was James Madison. He was the one who primarily drafted the Constitution. I'd like to see NR try to spin his writngs as being supportive of deferring to the legislative branch rather than actually enforcing the Constition as he understood it to mean.

You show me where Madison ever said the Courts had the exclusive and final say on the meaning of the Constitution. I have never seen where he did.

Of course Madison didn't think the courts had the final say - he helped write and defend the Virginia Resolutions, saying the states could protest the unconstitutional Sedition Act, even though Supreme Court judges (acting as trial judges) had upheld it.

In short, Madison was worried that the courts weren't doing *enough* to strike down unconstitutional laws, and some backup from the states was needed.

No. Madison thought the three branches and the states all four had a say in what the Constitution said. Root would disagree. Root thinks that the courts have the final say and should strike down any law that doesn't clearly meet their view of the Constitution and the other branches and the states get no say in the matter.

The method by which the other braches of government have "their say" is the same today as it always was - to simply refuse to obey what the courts have ruled.

Just as Andrew Jackson did.

There is that. And I would consider that legitimate. I seriously doubt Root would unless he liked the law in question. Ultimately Root's "philosophy" is nothing but good old "I want my pony" judicial activism. Root doesn't have a problem with courts upholding laws. He has a problem with courts not striking down laws he doesn't like but the public does.

Bingo. The system is designed to be contentious, whether between the branches or between the states and the federal government. This tension is the primary limiting factor of government power.

It's when all the branches and the states are getting along that we should worry the most.

For a Congressional statute to be enforced, there better be a consensus among the Pres, the Congress, the federal judiciary, and the states, and if not, it's a free-for-all, which is I think consistent with what at least *some* of the Founders would have wanted.

(Not Hamilton, I give you that).

You show me where Madison ever said that the courts should always defer to legislatures regardless of what the text of the Constitution said.

The judges are sworn to uphold the Constitution. They are not sworn to let the other branches decide for them what is or isn't Constitutional.

The courts should rule accordingly. If the other branches want to have their say, then they can refuse to obey the ruling. And then each of us can decide for ourselves what is or isn't legal and we can have a Mad Max free for all country.

You show me where Madison ever said that the courts should always defer to legislatures regardless of what the text of the Constitution said.

He didn't say that. And neither am I saying that. Only striking down laws when they clearly violate the Constitution is not the same thing as always deferring and stop pretending that it is.

And sure the courts should strike down unconstitutional laws. That however isn't the issue. The issue is what is an unconstitutional law. Root thinks such a law is any law the judge can find a reason to justify saying it does. I think such a law is a law that there isn't any reasonable way to conclude otherwise.

I still don't - and never will - buy your concept that the burden of proof lies on those taking the position that the government does not have the power to do something to prove that it does not.

The burden always lies on those claiming authority to exert force over others (and that is all that laws are - an exercise of force) to prove that they do, in fact, have that authority.

The fact is the constitution is silent on no thing. The eminent Robert Bork be damned. His problem is the 9th and 10th aren't nebulous descriptions of every right that he could judicially lay a finger on. So he claims the constitution is silent. Whereas the real rights ensconed in those two amendments are displayed by the actions of citizens and that is the only way they're discovered.

There, in those two amendments lie the nexus to dutifully nullify statutes that seek to erase those rights unenumerated. What kind of English language flunky takes unenumerated rights and makes it an expression of silence?

Shorter, National Review: All your Fourth Amendment are belong to us.