National Review Launches Another Attack on 'Libertarian Constitutionalism'

The conservative magazine doubles down on its defense of judicial deference.

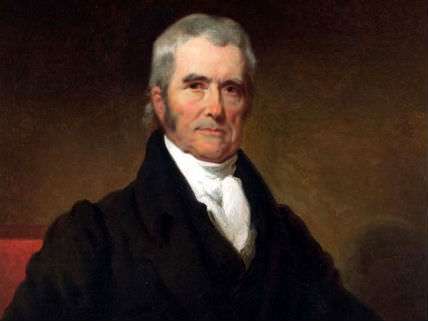

Last week I debated two writers from the conservative magazine National Review about several of the historical arguments made in my new book Overruled: The Long War for Control of the U.S. Supreme Court. In brief, National Review's Carson Holloway and Ramesh Ponnuru each asserted that my book's "libertarian constitutionalism" fails because it is at odds with the views of the founding fathers. According to National Review, the founding fathers consistently embraced the philosophy of judicial deference, which says that the courts should rarely—if ever—strike down statutes enacted by the democratically accountable branches of government. "John Marshall—the most consequential chief justice in the nation's history—was a proponent of judicial restraint," National Review declared.

What's the evidence for that assertion? "In Fletcher v. Peck (1810), Marshall held that judges should 'seldom if ever' declare a law unconstitutional 'in a doubtful case,'" National Review wrote. This week, National Review doubled down on that assertion.

So what's the truth of the matter? To be sure, John Marshall did make a nod in the direction of judicial restraint in Fletcher v. Peck. But guess what else Marshall did in that case? He ruled the actions of a state government to be unconstitutional. In fact, Fletcher v. Peck is one of the first cases in American history where the U.S. Supreme Court overruled a state legislature on constitutional grounds. Not exactly a shining beacon of judicial deference. To put it plainly, it's a real stretch to try and transform John Marshall—of all founding era figures—into the poster boy for judicial minimalism.

A second point of dispute between me and National Review is nicely captured in this statement by one of my two conservative opponents: "Root argues that judicial restraint, though many conservatives have championed it for decades, actually has progressive roots. I take it that this argument is meant to suggest that conservatives should be suspicious of the idea."

My book is primarily a work of legal history and my object was to understand and explain how the longstanding debate over the merits of judicial deference has shaped American law. And on this point the historical record is crystal clear: Progressive legal theorists and fellow travelers such as Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., James Bradley Thayer, Felix Frankfurter, Learned Hand, Hugo Black, and Alexander Bickel had an overwhelming and decisive influence on modern conservative advocates of judicial deference, such as the late Robert Bork. Indeed, as I previously noted, Bork himself openly and proudly credited the Progressives for their definitive influence upon him. In Bork's own telling, today's legal conservatism has firm Progressive roots.

Does that mean National Review should now be suspicious of Bork? Perhaps it should. After all, Bork certainly would have rejected National Review's dubious attempt to enlist John Marshall in the cause of judicial deference. According to Bork's 1991 bestseller, The Tempting of America, Marshall was "an activist judge" in many regards, including when it came to Marshall's "remarkable performance" (not a compliment) in none other than Fletcher v. Peck, in which Marshall "had to go well out of his way to float the idea that a court might strike down a statute even where 'the constitution is silent.'"

One final point. National Review's Carson Holloway wrote this week that nothing I've argued "proves that judicial deference is something progressives invented for progressive purposes."

But I never made that silly claim in my book (or anywhere else). Indeed, my book's first chapter chronicles the bitter debate over judicial deference which occurred in the aftermath of the Civil War and the ratification of the 14th Amendment—a period of history which clearly falls several decades before the Progressive movement came along.

My central point in this whole brouhaha with National Review is that today's legal conservatives owe a vast intellectual debt to the Progressive case for judicial deference, and that those same legal conservatives do not owe such a debt to founding fathers like John Marshall. What's more, today's legal conservatives routinely invoke Progressive (and New Deal) legal theories as justification for their own deferential judicial stances in a range of cases. And at the risk of repeating myself, let me just add that Robert Bork, the most influential conservative legal theorist of the past half century, agrees with me on all of that.

In other words, if the folks at National Review are so bothered by the Progressive roots of Borkian legal conservatism, their beef is with Bork himself, not with the uncomfortable historical evidence contained in my book.