National Review Urges Conservatives to Reject 'Libertarian Constitutionalism'

The fight over judicial deference divides libertarians and conservatives.

Writing in the March 9 issue of National Review, conservative writer Carson Holloway examines my new book Overruled: The Long War for Control of the U.S. Supreme Court. His focus is on the book's treatment of competing libertarian and conservative approaches to constitutional law. "Conservatives are defenders of judicial restraint or judicial deference," Holloway writes, which means they "admonish the courts to show deference to the will of the majority" and uphold most democratically enacted statutes. "Libertarian constitutionalism," on the other hand, seeks vigorous judicial action "in defense of individual rights."

Holloway kindly describes my book as "an informative and readable description, history, and defense of this libertarian constitutionalism." Nevertheless, he urges National Review's conservative readership to "decline…to buy what the libertarian legal movement is selling." Why? Because "the libertarian constitution is not the American Constitution, and the allegiance of American conservatives must be to the latter and not the former."

As support for this assertion, Holloway invokes the founding fathers, who, in his telling, consistently embraced the philosophy of judicial deference. "John Marshall—the most consequential chief justice in the nation's history—was a proponent of judicial restraint," Holloway says.

Perhaps. Yet Marshall was also the author of the Supreme Court's landmark 1803 opinion in Marbury v. Madison, which, to say the least, endorsed a rather robust vision of judicial power. Indeed, the idea of Marshall serving as the poster boy for judicial minimalism would have come as quite the shock to Thomas Jefferson, who was no fan of Marshall's penchant for wielding judicial authority. Marshall's "twistifications in the case of Marbury," Jefferson wrote in 1810, "shew how dexterously he can reconcile law to his personal biasses." Thirteen years later, in a letter to William Johnson, Jefferson was still complaining about Marshall's alleged judicial activism. "This case of Marbury and Madison is continually cited by bench and bar, as if it were settled law," Jefferson fumed.

Meanwhile, James Madison, one of the primary architects of the original U.S. Constitution, argued in a 1789 speech to Congress that amending the Constitution to include a Bill of Rights would prompt the judiciary to serve as "the guardians of those rights." In fact, Madison wrote, the judiciary "will be an impenetrable bulwark against every assumption of power in the legislative or executive." Not exactly a roaring defense of judicial deference.

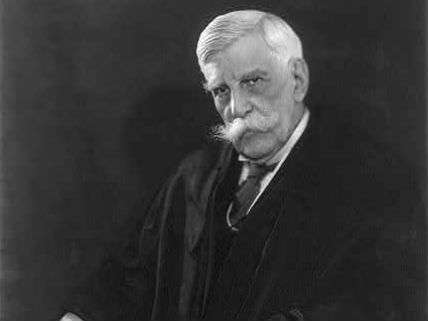

In reality, today's advocates of conservative judicial deference owe less to the 18th century founders and more to the turn-of-the-20th century Progressives, particularly to Progressive hero and thought leader Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. "A law should be called good," Holmes wrote, "if it reflects the will of the dominant forces of the community, even if it will take us to hell."

Conservative hero Robert Bork expressed that same idea (albeit in less colorful terms) in his 1991 book The Tempting of America. "In wide areas of life," Bork wrote, "majorities are entitled to rule, if they wish, simply because they are majorities."

What's more, this Holmes-Bork/Progressive-conservative connection has never been a secret. When President Ronald Reagan nominated Bork to the Supreme Court in 1987, for example, Bork was explicitly advertised as a Holmes devotee. "I would ask the committee and the American people to take the time to understand Judge Bork's approach to the Constitution," Sen. Bob Dole (R-Kan.) told the Senate Judiciary Committee during the Bork hearings. "That approach is based on 'judicial restraint'… Now, Judge Bork did not invent this concept," Dole explained. "It has been around for a long time. One of the most eloquent advocates was Oliver Wendell Holmes."

According to National Review, "conservatives must decide whether to buy what the libertarian legal movement is selling." I agree. But at the same time, conservatives must also decide whether to buy another round of what the Progressive legal movement already sold them.

Show Comments (224)