One-Third of Americans - and 51 Percent of Democrats - Favor Hate Speech Laws

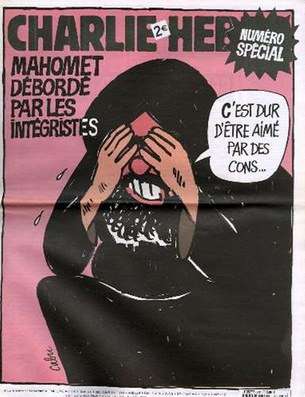

Today we are Charlie Hebdo. But what about tomorrow, and the day after tomorrow?

I think most observers would agree that over the past 20 years or so, we've been witnessing a paradox when it comes to free speech. On the one hand, it's easier than ever before to express oneself, especially in a public way (thank you, internet). On the other hand there is a huge attack on all sorts of speech that can in any way, shape, or form be deemed offensive. From trigger warnings to microaggressions and everything in between, all speech is suspect these days.

In popular culture, there are outliers such as South Park, Family Guy, and Tosh.O, where the envelope of taste and propriety is not so much pushed as shredded completely. Just in terms of comedy, does anyone think Inside Amy Schumer or Curb Your Enthusiasm's "Beloved Aunt" episode would have seen the light of day when Janet Reno, the Clinton administration, and all of Congress was voting overwhelmingly for the Communications Decency Act?

That terrible law would have regulated the emergent web like a broadcast network in the name of protecting kids from sexual material. It only was gutted after the Supreme Court struck it down in 1997. Christ, back in the 1990s, Bill Bennett and Joe Lieberman were giving our "Silver Sewer Awards" to Rupert Murdoch and the Fox Network for airing Married…With Children and The Simpsons, and The Weekly Standard was making "The Case for Censorship"!

And yet for all our expressive freedom, there's a huge pushback against speaking freely, especially on college campuses and in many news platforms. Chris Rock doesn't play colleges anymore because audiences are buzzkills:

I stopped playing colleges, and the reason is because they're way too conservative…. Not in their political views — not like they're voting Republican — but in their social views and their willingness not to offend anybody. Kids raised on a culture of "We're not going to keep score in the game because we don't want anybody to lose." Or just ignoring race to a fault. You can't say "the black kid over there." No, it's "the guy with the red shoes." You can't even be offensive on your way to being inoffensive.

As unimpeachable a progressive satirist as Stephen Colbert was targeted with a #CancelColbert campaign while mocking Redskins owner Dan Snyder's devotion to his team's nickname and mascot image. Lefty comic and actor Patton Oswalt no longer reads Salon because

…they write articles "Did The Onion Go Too Far?" or " Is Patton Oswalt Supporting Rape? " They already know the answer, but they know by feigning ignorance they can create all this debate about it. It upsets me because I used to really, and still do sometimes, love the articles Salon writes. They used to have Heather Havrilesky and Glenn Greenwald, and now they have become Fox News with all this look-y look-y shit. It hurts progressives. It's very personal but the fact is that that they want comedians to think twice, three times, four times about any kind of comedy.

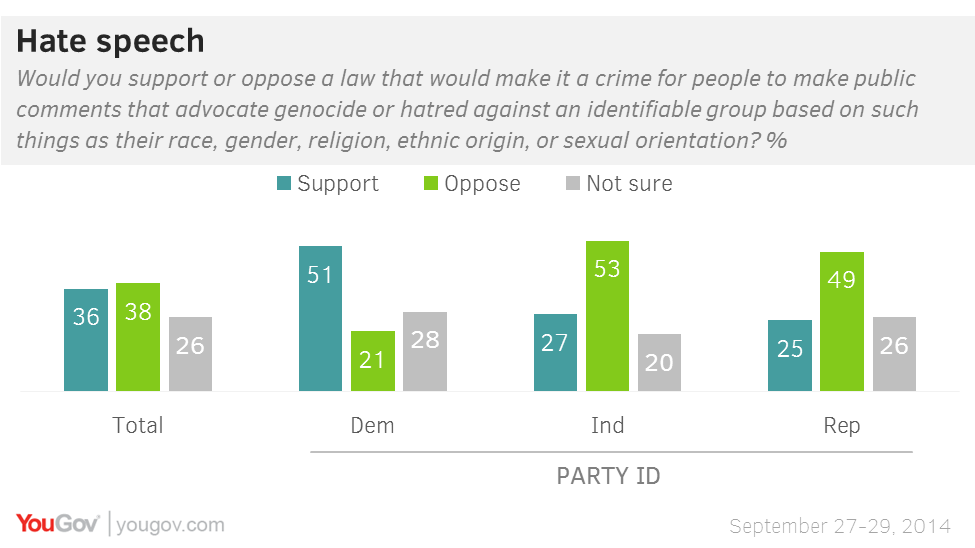

A YouGov poll taken just last fall found that equal amounts of Americans support and oppose "hate speech laws," defined as laws that would "make it a crime for people to make comments that advocate genocide or hatred against an identifiable group based on such things as their race, gender, religion, ethnic origin, or sexual orientation." Thirty-six percent said sure and 38 percent said no way. That's disturbing enough on its own, but here's something even more unsettling: Fully 51 percent of self-identified Democrats supported hate-speech laws.

That's not good.

I will not be surprised if the Charlie Hebdo massacre has the effect of increasing support for hate-speech laws in the United States (as Jacob Sullum has noted, hate-speech laws are already in place in France and most if not all European countries). Many Americans who don't particularly care about freedom of speech may look on the carnage and conclude it makes sense to avoid such scenes by stifling expression. Social Justice Warrior types will take another long look at Jeremy Waldron's 2012 book, The Harm in Hate Speech, and gussy up their interest in controlling thought and social interactions with philosophical language and social-scientific "rigor." Conservatives, sniffing out a possible way to screw liberals and libertarians, may rediscover The Weekly Standard's case for censorship and decide, hell, it makes a lot of sense. Aren't Christians the folks who are picked on in America and treated unfairly by the media and intellectuals? It's always "Piss Christ" and never "Piss Mohammed," right?

Which makes it more important not simply to show solidarity with the dead and wounded in France but to rehearse the arguments for unfettered trade in ideas and speech. A good place to start is the reissue of Jonathan Rauch's more-important-than-ever book Kindly Inquisitors. Originally released in 1994, the Cato Institute republished as 20th anniversary edition and Reason.com published a new foreword by Rauch.

The case for hate-speech prohibitions mistakes the cart for the horse, imagining that anti-hate laws are a cause of toleration when they are almost always a consequence. In democracies, minorities do not get fair, enforceable legal protections until after majorities have come around to supporting them. By the time a community is ready to punish intolerance legally, it will already be punishing intolerance culturally. At that point, turning haters into courtroom martyrs is unnecessary and often counterproductive.

In any case, we can be quite certain that hate-speech laws did not change America's attitude toward its gay and lesbian minority, because there were no hate-speech laws. Today, firm majorities accept the morality of homosexuality, know and esteem gay people, and endorse gay unions and families. What happened to turn the world upside-down?

Rauch tells the story of Franklin Kameny, a government astronomer who lost his job for being gay. How Kameny won it back is an epic story of slow-moving but ultimately triumphant justice. More important, Kameny and others like him never supported laws that would limit speech. Instead, writes Rauch, "They had arguments, and they had the right to make them."

Read the whole piece by Rauch if you care about the future of free expression, which is integral not just to identity politics but progress in science, religion, culture, economics, and every area of human flourishing. It will help remind you—and everyone you speak with—that threats to free speech do not always come from someone holding a gun and shouting Allahu Akbar. Indeed, they are more likely in America to come from people you know and respect.

Show Comments (154)