Amending the First Amendment: What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

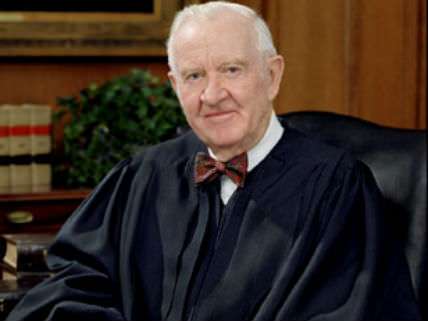

After the Supreme Court overturned restrictions on political speech by unions and corporations in the 2010 case Citizens United v. FEC, Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig proposed a solution: a narrower First Amendment. Lessig suggested an amendment stating that "nothing in this Constitution shall be construed to restrict the power to limit, though not to ban, campaign expenditures of non-citizens of the United States during the last 60 days before an election." When I asked him whether that amendment would authorize censorship of speech by corporate-owned news outlets, he reacted as if the possibility had not occurred to him. "It might well be important to make sure that nothing is intended to weaken or to draw into question the immunity granted by the First Amendment to the press," he said. "But that's certainly not my intent." I was amazed that Lessig, an avowed champion of free speech, could so blithely propose to amend the First Amendment without considering the potential for unintended consequences. New York Times legal writer Adam Liptak recently had a similar exchange with former Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, who wrote the dissent in Citizens United and is promoting his new book Six Amendments: How and Why We Should Change the Constitution:

One of those amendments would address Citizens United, which he wrote was "a giant step in the wrong direction."

The new amendment would override the First Amendment and allow Congress and the states to impose "reasonable limits on the amount of money that candidates for public office, or their supporters, may spend in election campaigns."

I asked whether the amendment would allow the government to prohibit newspapers from spending money to publish editorials endorsing candidates. He stared at the text of his proposed amendment for a little while. "The 'reasonable' would apply there," he said, "or might well be construed to apply there."

Or perhaps not. His tentative answer called to mind an exchange at the first Citizens United argument, when a government lawyer told the court that Congress could in theory ban books urging the election of political candidates.

Justice Stevens said he would not go that far.

"Perhaps you could put a limit on the times of publication or something," he said. "You certainly couldn't totally prohibit writing a book."

As you may recall, the First Amendment that Deputy Solicitor General Malcolm Stewart had in mind when he said banning books would be constitutional—an answer that seemed to be a turning point in the case—was the unimproved version, the one that rules out any law "abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press." Imagine how much fun government lawyers could have with the versions of the First Amendment preferred by Lessig and Stevens.

As Damon Root noted last week, Stevens also wants to fix the Second Amendment.

Show Comments (102)