Why Can't Anyone Agree How Many Mass Shootings There Have Been In 2013?

Making sense of the competing statistics

If you've been following the news in the wake of the Washington Navy Yard massacre, you might be hopelessly confused about how frequently mass shootings happen in the United States. The Huffington Post reports that there have been at least 16 mass shootings this year so far, killing a total of 78 people. Mother Jones, on the other hand, has updated its much-cited "Guide to Mass Shootings" with the news that the Navy Yard murders were "the fifth mass shooting in the United States this year." An article by Annie Linsky at Bloomberg doesn't offer a count for 2013, but it does stress how rare such crimes are. That Huffington Post piece, by contrast, talks about how "common" mass shootings have "become."

As you might have guessed, different reporters are using different definitions of "mass shooting." We've waded through this thicket of competing numbers before, and if you want to get into the statistical weeds I can point you to a couple of posts I wrote last year, "Are Mass Shootings Becoming More Common in the United States?" and "Making Sense of Mass-Shooting Statistics." Here's the key points to remember as you read the numbers floating around in the press:

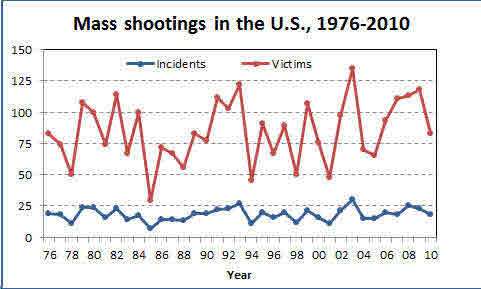

• The simplest definition of a mass shooting is a gun crime in which at least four people other than the shooter are killed. Over the decades the number of these murders has zig-zagged up and down without a discernable pattern. This chart stops in 2010, so it doesn't cover the last few years, but it should get across what I mean:

This seems to be the definition that The Huffington Post is using. As you can see, their numbers for 2013 are not drastically different from the figures we've seen stretching back into the Ford era (though of course we don't know what will happen in the next three months). It is thus misleading to treat that data as a sign of how "common" such incidents have "become." (I should note as well that the chart above covers raw numbers, not incidents or casualties per capita. U.S. population has grown considerably since 1976.)

• The chief objection to that definition is that when people hear "mass shooting" they think of random shootings in public places, not just any slaying involving multiple bodies and a gun. If you read past the infographic in the Huffington Post story and look at the details of the crimes, you'll find a drug deal gone wrong, a husband who shot his wife and then started killing witnesses, and several other sad stories, but very few events that resemble the Newtown or Navy Yard murders. Hence the lower figure from Mother Jones.

That said, Mother Jones' definition is a somewhat jerry-rigged thing that has been criticized harshly for its inconsistencies and exceptions. (See Michael Siegel's critique here and James Alan Fox's critique here.) A better source is Grant Duwe, a criminologist at the Minnesota Department of Corrections, who keeps a count of mass shootings that take place in public and are not a byproduct of some other felony. (He would not, for example, include a robber who shoots several people while sticking up a store.) While Mother Jones presented a portrait of a steadily increasing social problem, Duwe's figures show more incidents than usual in 2012 but an ongoing decline from 1999 to 2011. He does not have an ongoing count to offer for 2013 -- he assembles his figures annually, not monthly or weekly -- but he tells me that the last time there was a sudden spike in incidents, back in 1999, the following years saw a regression to the mean; he hopes the same will be true following 2012. (As do we all, as do we all.)

[Update: A reader just informed me of another definition that's being used by an anti-gun community on Reddit -- one that's broader rather than narrower than the Huffington Post piece's approach. The thinking there is that a "mass shooting" need not involve four or more dead people, just four or more people struck by bullets. They list a larger number of incidents for 2013, which shouldn't be surprising: If you count more, you're gonna count more. (Using their approach, for example, this story about a limo driver returning fire at some would-be thieves qualifies as a mass shooting.) They don't have data for past years, so they don't have a trendline we can compare to the trendlines for the other definitions.]

• The most important thing to know about mass-shooting stats is the point Linsky made in her Bloomberg piece: They account for just a tiny fraction of American murders. The larger murder rate is a much more important trend. And the news on that front is mostly good.

The FBI has just released its crime statistics for 2012. The bad news is that the murder rate for that year was 0.4 percent higher than the rate for the year before. The good news is that the murder rate was nonetheless 12.8 percent lower than where it was half a decade ago. Something similar has happened with violent crimes in general: There were slightly more of them in 2012 than in 2011, but the rate stayed essentially the same as the previous year and was far less than it was back in 2008. It has been steadily dropping, in fact, since the early 1990s.

So the long-term trend has been toward less violence, even if it feels like you're seeing more violence on TV. That isn't much consolation for the people who lost loved ones at the Navy Yard. But you should bear it in mind if you spot any politicians stampeding toward the carnage with tough-on-crime talking points on their lips and hastily written bills in their fists.

Show Comments (56)