The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Thoughts on the Declining Numbers of SCOTUS Clerks Becoming Law Professors

One track became two.

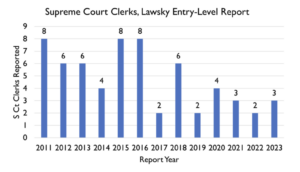

From 1940 to 1990, about one third of Supreme Court law clerks became law professors. But in recent years, Brian Leiter and Jeff Gordon note, that percentage has dropped considerably. Sarah Lawsky has some numbers of clerks entering legal academia in the last decade or so that Brian recently posted:

Even if Sarah is missing some former clerks in her numbers, that's a noticeable drop. What explains the trend? Over in the comments to Brian's post, Professor Dan Epps has a suggestion that I think explains a lot: The increasing separateness of the law clerk and law professor track.

I realize this is a niche topic, but here's a little background to explain that increasing separateness for those who may be interested. It used to be, decades ago, that getting a top clerkship and getting a top professorship were the same track. If you were a law student and you wanted to be a law professor, you got the highest grades you could and tried to use your grades to get a clerkship with the most prestigious judge you could. The clerkship acted as a sort of graduate degree in law. If you hit the jackpot and clerked on the Supreme Court, that was reasonably likely to lead to a professorship at a very good law school. The top schools tried to hire former clerks, with some law school Deans visiting the Supreme Court to meet with clerks and pitch becoming a professor at their schools. This was the era of 1940 to 1990, noted at the top of the post, when about one third of clerks later became professors.

These days, by contrast, the paths are a lot more separate. First, there's more of a multi-year process of planning for a Supreme Court clerkship. Most Supreme Court clerks now have multiple prior clerkships before starting at the Supreme Court—according to David Lat, 29 of the current 36 clerks had two or more clerkships before their current positions. And those are often spaced out, too. Just skimming the list at David's site, it looks like a typical clerk graduated about 3-4 years before starting at the Supreme Court. By the time you're done with the Supreme Court, you're 4-5 years out of law school and you may still only have a year or so of actual legal practice. Meanwhile, biglaw firms await with what are now apparently $500,000 clerkship bonuses if you join them.

If you want to become a law professor, on the other hand, the pathways today tend to be different. Law schools are now evaluating potential entry-level professors much more on their scholarship than on their grades or clerkships. As a practical matter, you need to have spent a few years researching and writing scholarship to get ready to go on the market for a tenure-track job. Getting a Ph.D. has become a very common way to develop a scholarly methodology and start to write some articles. At most top schools I am aware of, a clear majority of recent entry-level hires have one. And even if you don't have a Ph.D., you will probably need to spend two years at a law school as a Fellow or Visiting Assistant Professor (VAP), learning the quirky ways of academia and working on an article or two to get ready for the entry-level market. As Sarah Lawsky has found, about 90% of new entry-level hires have either a fellowship or a doctorate. Many have both.

The takeaway of all this, I think, is that the single path of decades ago has largely divided into two separate paths. Once you're in law school, the way to maximize your odds of getting a Supreme Court clerkship is different from the way to maximize your odds of getting a professorship, especially at a top school. I think this largely explains why we see fewer people today succeeding on both tracks, first clerking at the Supreme Court and then later becoming an academic. It's not the only explanation. But I think it's the main one.

As I said earlier, this is a niche topic. Some readers (if anyone is still reading) may be wondering, "Who cares?" And totally fair if you don't. This may just be navel-gazing that has no significance outside the faculty lounge. But I wonder if it may also be a small signal of a broader change of the role and background of law professors, and in turn, of law schools. As Richard Posner noted in the 2007 essay I blogged about last month, there has been a switch over the decades from the model of the law professor as top lawyer steeped in lawyering to the model of the law professor as academic who writes and teaches in the field of law. I wonder if the declining number of former Supreme Court clerks entering academia might be one small indicator of that switch continuing.

UPDATE: If there are recent clerks or recently-appointed profs (or both) who want to weigh in on this, I'd be happy to post reactions as to their sense of this and whether they agree. Happy to remove names if requested, too. Just send me an email, orin at berkeley dot edu.

Show Comments (31)