The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Thoughts on the Declining Numbers of SCOTUS Clerks Becoming Law Professors

One track became two.

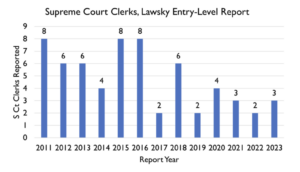

From 1940 to 1990, about one third of Supreme Court law clerks became law professors. But in recent years, Brian Leiter and Jeff Gordon note, that percentage has dropped considerably. Sarah Lawsky has some numbers of clerks entering legal academia in the last decade or so that Brian recently posted:

Even if Sarah is missing some former clerks in her numbers, that's a noticeable drop. What explains the trend? Over in the comments to Brian's post, Professor Dan Epps has a suggestion that I think explains a lot: The increasing separateness of the law clerk and law professor track.

I realize this is a niche topic, but here's a little background to explain that increasing separateness for those who may be interested. It used to be, decades ago, that getting a top clerkship and getting a top professorship were the same track. If you were a law student and you wanted to be a law professor, you got the highest grades you could and tried to use your grades to get a clerkship with the most prestigious judge you could. The clerkship acted as a sort of graduate degree in law. If you hit the jackpot and clerked on the Supreme Court, that was reasonably likely to lead to a professorship at a very good law school. The top schools tried to hire former clerks, with some law school Deans visiting the Supreme Court to meet with clerks and pitch becoming a professor at their schools. This was the era of 1940 to 1990, noted at the top of the post, when about one third of clerks later became professors.

These days, by contrast, the paths are a lot more separate. First, there's more of a multi-year process of planning for a Supreme Court clerkship. Most Supreme Court clerks now have multiple prior clerkships before starting at the Supreme Court—according to David Lat, 29 of the current 36 clerks had two or more clerkships before their current positions. And those are often spaced out, too. Just skimming the list at David's site, it looks like a typical clerk graduated about 3-4 years before starting at the Supreme Court. By the time you're done with the Supreme Court, you're 4-5 years out of law school and you may still only have a year or so of actual legal practice. Meanwhile, biglaw firms await with what are now apparently $500,000 clerkship bonuses if you join them.

If you want to become a law professor, on the other hand, the pathways today tend to be different. Law schools are now evaluating potential entry-level professors much more on their scholarship than on their grades or clerkships. As a practical matter, you need to have spent a few years researching and writing scholarship to get ready to go on the market for a tenure-track job. Getting a Ph.D. has become a very common way to develop a scholarly methodology and start to write some articles. At most top schools I am aware of, a clear majority of recent entry-level hires have one. And even if you don't have a Ph.D., you will probably need to spend two years at a law school as a Fellow or Visiting Assistant Professor (VAP), learning the quirky ways of academia and working on an article or two to get ready for the entry-level market. As Sarah Lawsky has found, about 90% of new entry-level hires have either a fellowship or a doctorate. Many have both.

The takeaway of all this, I think, is that the single path of decades ago has largely divided into two separate paths. Once you're in law school, the way to maximize your odds of getting a Supreme Court clerkship is different from the way to maximize your odds of getting a professorship, especially at a top school. I think this largely explains why we see fewer people today succeeding on both tracks, first clerking at the Supreme Court and then later becoming an academic. It's not the only explanation. But I think it's the main one.

As I said earlier, this is a niche topic. Some readers (if anyone is still reading) may be wondering, "Who cares?" And totally fair if you don't. This may just be navel-gazing that has no significance outside the faculty lounge. But I wonder if it may also be a small signal of a broader change of the role and background of law professors, and in turn, of law schools. As Richard Posner noted in the 2007 essay I blogged about last month, there has been a switch over the decades from the model of the law professor as top lawyer steeped in lawyering to the model of the law professor as academic who writes and teaches in the field of law. I wonder if the declining number of former Supreme Court clerks entering academia might be one small indicator of that switch continuing.

UPDATE: If there are recent clerks or recently-appointed profs (or both) who want to weigh in on this, I'd be happy to post reactions as to their sense of this and whether they agree. Happy to remove names if requested, too. Just send me an email, orin at berkeley dot edu.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"there has been a switch over the decades from the model of the law professor as top lawyer steeped in lawyering to the model of the law professor as academic who writes and teaches in the field of law."

I think the bigger question is why is Big Law hiring former clerks and not law professors? First, why are they hiring *either*?

Why is Big Law paying a premium for former clerks? And why do they not think that law professors have the same qualities? After all, couldn't Big Law get law professors if it wanted to?

Could it be an increasing schism between the actual law and what law school professors say it is?

The exact opposite is happening in medical schools. Med school professors are MDs at the top of their various specialty, practicing it while they teach. And if you have a complicated medical problem, you go to a medical professor. Not so anymore with a complicated legal problem.

And this is why I think that law schools, like much of higher ed, are dying.

I'm not sure I follow: Why should law firms not hiring people who already have a job at law schools (and who may have left law firms to get that other job) mean that law schools are dying?

People leaving law firms to be professors flies in the face of your 2-track thesis.

I don't know why. If you're at a law firm and you'd rather be a professor, the decision to leave doesn't (as far as I can tell) shed light on the PhD vs. Supreme Court clerk track.

As hard as it may be to get a Big Law job it is harder to get a law professor job (less positions). The number of law professors that want to move to Big Law is virtually zero. They chose academia over practice. So, no Big Law couldn't get law professors if they wanted because the professors have self selected academia over practice

ARE THERE fewer positions?

I'm all for qualitative research, but you gotta start with the number of annual vacancies in both. Etc.

There are only about 200 law schools, and not all of them hire every year. There definitely more law firms that would be considered big law, and they basically all hire every year (whether some of the best boutique law firms are considered big law is questionable as they have the prestige but not the size).

But mathematically the shortage of law faculty jobs ought not affect the ability of law schools to hire candidates who had been clerks if said ex-clerks all wanted to be law professors.

Sure, few of them would be hired due to the few openings, but they would be competing against each other for these few openings.

Hence either the ex-clerks don't want to become law professors anymore, or the law schools now value other criteria (e.g. PhDs), or both. Or they are being priced out of the market.

It is likely that Dr. Ed 2's thoughts on higher education reflect the failing of his own academic career.

Say what you want, if you objectively look at it as an industry, higher education is in serious trouble.

Strictly speaking, I don't think "janitor at a university" is accurately characterized as an academic career. Nor do I think it gives him any insights into the operations of law schools (which the campus at which he does his janitoring does not even have).

I was a janitor when I was in high school, feces for brains, and it was at a nursing home, not a college.

That said, I'll throw out my hypothesis for others to critique.

I've long said that law schools are different from most of academia because they do not require a terminal degree of their faculty. Well, the OP mentioned a higher percentage of faculty applicants with terminal degrees.

Second, while one can argue that a clerk winds up knowing the judge or knowing the law, but a clerk definitely leaves knowing something, and who's bidding the most for it?

My hypothesis is that law schools are converting into law colleges -- with all of the distinctions between a "school" and a "college" within both a university and academia as a whole -- a complicated subject that people debate -- but can sorta be summarized as the distinction between an academic field which prepares young people to enter a profession versus an academic field which attempts to extend the knowledge of the field.

It's Schools of Education and Nursing because the primary purpose of the academic division is to prepare graduates to be licensed as K-12 teachers or RN nurses. It's Colleges of Language and Literature or Arts and Humanities because you don't have the same primary purpose.

My point that law schools are dying is twofold -- first they are becoming law *colleges* and shifting away from their primary mission being preparing young professionals for entry, and second, I don't think there is a market for law *colleges*, at least in the current model of student-paid tuition.

Big Law is relatively new and I don't know how much political power it has, but what if it decided that it was cheaper to teach law in house than pay a premium for young JDs (who they are already teaching in house) -- and got the bar rules changed so they could license their own people? What would that do to a lot of law schools?

Let me rephrase the question -- how many law students are paying big bucks today to learn about the research their professors are conducting and how many are simply there to get their Bar Card?

Your ideas are marvelously untainted by any knowledge of law schools or the legal profession.

And you need to realize that the ad hominem fallacy is not an answer.

Pro tip: you're using big words you don't understand.

"Dr. Ed's ideas about law school are terrible because he wants to murder sex workers." would be an ad hominem fallacy. "Dr. Ed's ideas about law school are terrible because he doesn't know anything about law school or the legal profession" is not in fact a fallacy.

Rare footage of Dr. Ed at work.

And what do the stats say about the relative likelihood of the Clerk => Prof track, broken down by party, ie whether the clerk clerked for a GOP appointed Justice or a Dem appointed one ?

My hypothesis is that for SCOTUS clerks there'll be more Dem clerks going to Prof than GOP clerks, and as you move down the food chain to less exalted clerks, the gap will widen.

This btw is the absolute best type of hypothesis because it is not polluted by any facts at all.

OTOH, there is the underlying presumption that the number of clerkship and professor positions has remained constant since 1950 -- and it hasn't.

1: If people are now doing 3 clerkships, that means only 1/3 as many people can clerk, unless more are hired. Annual number of *first-time* clerks 1950-2020?

2: Law faculty hiring has not remained constant since 1950. It increased 1960-80, decreased 2008-13, and varied elsewhere.

That was my thought: There are more Republican nominated judges these days, and the major law schools are now pretty relentless about not hiring conservative faculty.

So maybe having clerked for a Republican nominated judge is the sort of thing that now makes it impossible to get hired at many law schools?

That's the sort of thing a nominating party breakdown would reveal.

How long have law firms offered $500,000 signing bonuses (or the inflation-adjusted equivalent) and salaries comparable to current salaries?

I wonder if there aren't other factors as well.

The increasing number of boutique law firms that do appellate/SCOTUS work and are eager to hire former SCOTUS and federal appellate clerks means that there is a credible intellectually appealing alternative to becoming a law prof.

Given the competitive academic job market, I also wonder if it might not be just as effective for the clerk oriented students to aim for a judgeship or high profile work at a boutique firm and then use that to open the academic door to them.

If your data is good, the person who went clerk -- judge -- academic would still show up as having been a clerk.

Also big firms have SCOTUS/federal appellate focused practice groups that also do pro bono SCOTUS work to burnish their credentials. You'll continue working on the high level stuff, instead of going from SCOTUS work to doc review and discovery fights.

Right-wing justices hire right-wing clerks.

How many law faculties — especially legitimate, strong, reason-based law faculties — are or should be in the market for candidates

who are bigots (or in some cases merely sympathetic and aligned with bigots);

who prefer superstition, dogma, and nonsense to reason, science, and the reality-based world;

who can’t stand modern America and all of this damned progress;

and

who want to advance the causes of race-targeting vote suppressors, gay-bashing jerks, un-American insurrectionists, fundamentalist religious kooks, and those who strive to create safe spaces for America’s vestigial bigots?

Strong law schools became strong by refraining from hiring people who would wish to be (or would be hired as) Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Barrett, or Kavanaugh clerks. Why would our best schools want to start emulating weak schools by hiring movement conservative, Republican faculties?

I doubt that this is the sole factor influencing the relevant development, but any analysis that does not acknowledge this factor seems paltry.

Histrionics aside, I wonder if the Reverend has a point. Might one cause be that law schools hire few if any conservatives and more SCOTUS clerks are conservative given Court's composition?

It would take further analysis to prove, but that seems likely to me.

Better law schools tried hiring clerks who were movement conservatives for faculty positions. Those schools seem to have learned from those mistakes (and, in some cases, to be correcting the problem); I doubt they are in the market for more aggravation along that line.

Why do you think hiring those few conservatives/libertarians was a mistake, and what are the aggravations they caused?

(1) Are there more law clerks now (SC and prestigious appellate), and the same number or fewer law prof jobs?

(2) Is there a list somewhere with names of clerks who became professors? (or just of clerks?) I'd like ot see which what names I recognize. Were the old clerk hires as law profs successful? Maybe they turned out to be duds, and academia caught on. I've heard the joke about how your first year grades get you on law review, which gets you your first clerkship, which gets you your second, which gets you the SC one, which gets you the law prof job.

...there has been a switch over the decades from the model of the law professor as top lawyer steeped in lawyering to the model of the law professor as academic who writes and teaches in the field of law.

That is interesting. How does that change the way law students are taught?

It’s more of a gravy train now. Law professors don’t make much.