What is the average price of a textbook in the nearest college campus bookstore? Before you answer, is it greater or less than $7,128.53?

Most people quickly agree that the average price of a textbook is less than that absurdly high amount. But contemplating that outrageous number affects judgment. When first given an absurdly high numeric reference point people make higher estimates of the average price of a textbook then when they are not first provided with this reference point.

Psychologists call this phenomenon "anchoring." Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman first demonstrated that people tend to rely on numeric reference points when making numeric judgments. Doing so is a helpful and useful mental shortcut. If you are going to buy a new car with a sticker price of $36,345, you know that you likely will not pay that amount. You might negotiate that number down and there might be additions not listed. The sticker price, however, provides a good estimate of the final price. Anchoring is a thus useful way to estimate how much you will pay for the car. Problems arise when anchors influence judgment even when they are meaningless or arbitrary.

Psychologists have shown that all manner of numeric reference points influence numeric judgments, no matter how bizarre or fanciful. In one study researchers asked undergraduates to identify the year that Attila the Hun was defeated. In this study researchers first asked their subjects whether Attila the Hun was defeated before or after the year corresponding to the last three digits of their phone number plus 400 (A.D.). Then they asked subjects to identify when Attila was defeated. (For the record, Attila suffered his only defeat at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains in 451 A.D.). The students certainly knew that their numbers had nothing to do with Attila the Hun, but their guesses correlated remarkably with their phone numbers.

Psychologists have proposed three main theories to explain the influence of anchoring. Tversky and Kahneman believed that people adjust inadequately from the anchor. They proposed that cognitive effort is required to adjust mentally the anchor down (or up) to the correct estimate and that people commonly fail to put in enough cognitive effort. If so, the starting point would thus affect the final estimate. Other psychologists suggested that once people entertain the possibility that the anchor is correct, their evaluation of that anchor guides how they arrive at the actual estimate. For example, when people contemplate whether the price of the average textbook exceeds $7,000, they call to mind examples of inordinately expensive textbooks. Although even the most expensive books are not that pricey (not yet!) considering whether that inordinately high number is accurate calls to mind expensive examples of textbooks, which in turn influence their estimate of the average price.

Finally, others suggest that anchors temporarily alter perception, creating an illusion of judgment. Just as an adult can seem small when standing next to an elephant and large when standing next to a cat, anchors induce people to perceive reasonable estimates as either too large or too small in comparison. Having just considered whether the average price of a textbook exceeds $7,000, an estimate of $150 seems too small. All three of these influences might be at play because anchoring is a potent and reliable phenomenon.

Judges commonly must make numeric estimates when determining damage awards, criminal sentences, bail amounts, or civil fines. Suggestions from lawyers, statutory damage caps, or insurance policy limits can anchor judges' decisions. Using experimental methods with sitting judges as research subjects, we have found that anchors have profound effects on judges.

In one of our studies, federal judges who first considered a frivolous motion to dismiss for failure to meet the jurisdictional amount of $75,000 in a diversity action in federal court awarded 29% less in a serious personal injury case than judges who did not have to rule on the motion. We found that offers made during settlement discussions in a civil case anchored judges' ultimate awards—even though we reminded these judges that discussions during settlement talks are inadmissible.

We also showed that damage caps influenced civil damage awards of American, Canadian, and Dutch judges. In a criminal context, judges anchored on sentences in unrelated cases; that is, after sentencing a defendant in a minor case to several months in prison, judges then sentenced a more serious offender to far less time than when the order of the cases had been reversed.

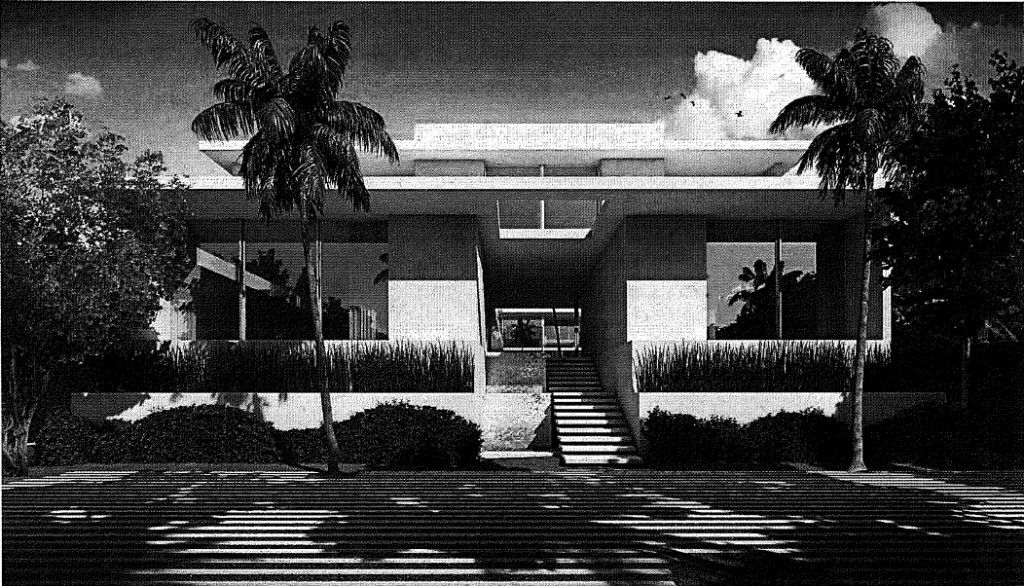

Every anchor we tested influenced judges. We thus began experimenting with an outlandish anchor. We created a hypothetical case for judges in which we described a roadhouse (or a "club") that had violated a local noise ordinance. Our materials stated that the roadhouse had put a band out on an outside deck late into the evening on a couple of occasions in its opening week, disturbing nearby residents. We asked 526 judges from seven different jurisdictions to identify an appropriate fine that would be sufficient to deter future misconduct and appropriately reflect the "degree of disruption" that the roadhouse had caused to its neighbors. For half of the judges, we identified the facility as "Roadhouse 58", named after its street address; for the other half of the judges, we called it "Roadhouse 11,866," also named after its address.

Roadhouse 11,866 would be well advised to either remain quiet at night or change its name. The median fine judges levied on Roadhouse 11,866 was $1,683, as compared to $1,000 against Roadhouse 58. The difference between the groups was significant. (Mann-Whitney test, z = 2.03, p =.04.) Although the address was irrelevant, it clearly drew the judges' attention. Seven of the judges evaluating Roadhouse 11,866 levied a fine of $11,866!

Making numeric evaluations is difficult. No natural metric exists to convert a qualitative degree of pain and suffering into a quantitative dollar value, nor a sense of desert into a number of years in prison. Judges (and juries) must nevertheless perform this task constantly. Research on anchoring suggests that the task will be influenced by misleading influences like irrelevant anchors.

What can be done? The only sure-fire cure for the influence of misleading anchors is to avoid learning about them, but that is impossible in many cases. Counter-anchors are not effective either, as research suggests that decision makers will focus on one of the available anchors. Well-crafted constraints like sentencing guidelines can contain the influence of irrelevant anchors, although they might introduce other structural problems. Reasonable anchors hold some promise. Recent research by Valerie Hans and Valerie Reyna suggests that people are more apt to be influenced by meaningful, reasonable anchors than misleading, unreasonable ones. To the extent judges can either avoid exposure to anchors, rely on sensible guidelines, or identify reasonable anchors, they can avoid some of the erratic influence of anchors.

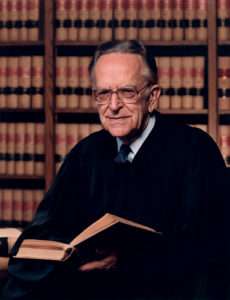

Our full article on anchoring in judges: Jeffrey J. Rachlinski, Andrew J. Wistrich & Chris Guthrie, Can Judges Make Reliable Numeric Judgments? Distorted Damages and Skewed Sentences, 90 Indiana L.J. 695 (2015).

Tomorrow: Gains and Losses: The Arbitrary Effect of Decision Frame.

Show Comments (18)