The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

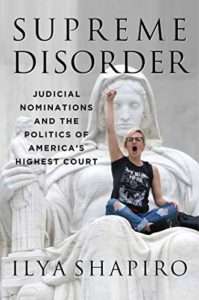

Review of Ilya Shapiro's "Supreme Disorder"

One Ilya reviews a book written by another. Hopefully, this won't exacerbate #IlyaConfusion!

In this post, I review Ilya Shapiro's important new book Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of America's Highest Court. Unfortunately, the "other" Ilya and I often get confused with each other. To prevent this review from fostering the growth of the pernicious phenomenon of #IlyaConfusion, I recommend reading my definitive guide to telling the two Ilyas apart. On to the actual review!

It's hard to think of a better-timed book than Ilya Shapiro's Supreme Disorder. The book was officially released in September, just a few days after the passing of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. That event soon led to Donald Trump's nomination of Amy Coney Barrett to fill the seat in a rushed confirmation process that concluded just before the 2020 presidential election. Democrats understandably cried foul, and pointed out how the GOP's actions contradicted their own insistence, in 2016 (when President Barack Obama nominated Merrick Garland to fill the seat vacated by the death of Justice Antonin Scalia), that Supreme Court nominations should not be taken up in an election year.

The clashes over the Garland and Barrett nominations were just part of a long series of other partisan conflicts over Supreme Court seats, including the bitterly contested nominations of Robert Bork, Clarence Thomas, Brett Kavanaugh, and others. Long gone are the days when SCOTUS nominees were routinely confirmed with little or no controversy.

Ilya Shapiro's book is not only timely, but also invaluable as a guide to the history of political battles over Supreme Court nominations, as well as a thorough discussion of possible reform proposals to improve the confirmation process. He traces the history of those conflicts from the early days of the republic on through the bitter fight over the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh in 2018.

As Shapiro shows, conflict over nominations is not a new thing. In the early 1800s, the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans each maneuvered in various ways to gain control of the courts. Later, in the 1860s, the Republican Party twice adjusted the size of the Court - each time primarily for the purpose of securing a majority of justices amenable to the party's positions on various key constitutional issues. Franklin D. Roosevelt's 1937 court-packing plan was a less successful effort to achieve a similar result (though some historians still argue that the threat of court packing triggered a "switch in time that saved nine," even as the dominant view among scholars has shifted away from that position).

At the same time, Shapiro describes how, during many periods in American history, Supreme Court nominations attracted little or no controversy. For example, John F. Kennedy's 1962 nomination of Byron White resulted in only a brief, perfunctory Senate hearing, much of which was devoted to discussion of White's earlier career as an professional football player! Such a process is almost unimaginable today.

As Shapiro explains, the key difference between 1962 and the present day is not that politicians were nicer back then or that judicial nominees were better qualified, but that in 1962 there was much less polarization on legal issues between the two major parties. Today, there is a stark difference between Republican and Democratic SCOTUS nominees on both methodology (originalism vs. living constitutionalism) and likely votes on specific issues, such as abortion, gun rights, religious liberties, executive power, campaign finance regulation, and much else. By contrast, such partisan differences between nominees were much more modest in the 1960s - and during other periods when SCOTUS nominations attracted little controversy.

In the part of his book devoted to more recent events, Shapiro traces the gradual increase in conflict over Supreme Court nominations during the last several decades. One symptom of the growing conflict is that Democrats and Republicans each have their own conflicting narratives about when the conflict began and who is responsible. Each claims that it was the other party that violated norms, while they themselves only acted defensively.

Although Shapiro is, on the whole, more sympathetic to the conservative side than the liberal one, it is to his credit that he provides as balanced an account of this history as we are likely to get. For example, many conservatives point to the defeat of Robert Bork's nomination in 1987 as a precedent-shattering event that destroyed previous norms of Senatorial deference to "qualified" nominees. Bork's defeat was indeed a notable turning point in the conflict. But, as Shapiro explains, it was prefigured by such earlier events as Republicans' successful maneuvering (with the aid of conservative Democrats), to block the elevation of Justice Abe Fortas to the position of Chief Justice in 1968-69, thereby enabling Richard Nixon to appoint the more conservative Warren Burger to the post after he narrowly won the 1968 election. Still earlier, segregationist senators had (albeit unsuccessfully) forcefully opposed the nomination of appointees seen as sympathetic to civil rights (most notably Thurgood Marshall in 1967).

Shapiro also notes that, while Bork was the victim of some ridiculous and scurrilous charges (such as bogus claims that he sought to bring back the days of segregation and slavery), he also held views on some issues that really were out of the mainstream, and are today rejected by most conservative judges and legal scholars. Among other things, he believed that the Bill of Rights was not properly "incorporated" against state and local governments, and had an extremely narrow view of freedom of speech. Viewed in historical perspective, the Bork nomination was not a sudden break with the past, but rather an escalation of a conflict that had already begun, as the parties diverged more on key legal issues in the late 1960s and 1970s.

More recent judicial nomination battles also feature gradual escalation, as opposed to completely unprovoked aggression by one side or the other. For example, the GOP's blocking of the Garland nomination in 2016 was prefigured by Democrats' very similar tactics in blocking a series of GOP lower-court nominees in the early 2000s, including some that were seen as likely future Supreme Court nominees (such as DC Circuit nominees Peter Keisler and Miguel Estrada). In all of these cases, the Democrats sat on the nomination for years, without letting it come up for a vote (much as the GOP later sat on the Garland nomination). Prominent Democrats (including then-Senator Joe Biden) also threatened to block GOP SCOTUS nominees in election years in 1992 and 2008 (though the opportunity to act on this intention did not actually arise in those years).

Blocking a Supreme Court nominee without a vote was an escalation that went beyond previous shenanigans. But it did not arise in a vacuum. The same goes for the GOP's 2017 repeal of the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees (adopted to push through the nomination of Neil Gorsuch), which built on the Democrats' earlier 2013 abolition of the filibuster for lower-court nominees (in order to push through Obama nominees opposed by GOP senators). The Democrats' actions, of course, were a response to GOP efforts to block Obama's nominees, which in turn were in part a reaction to Democrats' blocking of various George W. Bush nominees. And so it goes.

Ultimately, as Shapiro effectively explains, the roots of such skullduggery reside less in the nefarious nature of specific politicians, than in the growth of partisan polarization. The more nominees of different parties systematically diverge on key issues, the greater the incentive to block opposing-party nominees, and ram through your own - regardless of norms.

While Shapiro makes a strong effort at balance, in a few instances his relatively greater sympathy for the conservative side in these battles does lead him astray. For example, he suggests that the debate triggered by the sexual assault accusation against Brett Kavanaugh during his 2018 confirmation hearing "wasn't really about Kavanaugh," but about liberal Democrats' opposition to GOP SCOTUS nominees more generally. In reality, a plausible accusation of assault would have triggered strong opposition even during less contentious periods. The real difference is that, during an era with less polarization, a nomination with such a cloud over it would likely have simply been withdrawn. The president could take such action confident in the knowledge that the Senate would go on to confirm another nominee with a similar judicial philosophy, but no hint of scandal. And the opposition party (at least most of it) would accept the new nominee.

In 2018, the Republicans dug in on the Kavanaugh nomination in large part because they feared that withdrawing it would enable the Democrats to "run out the clock" until the 2018 midterm election after which the party might have a stronger position in the Senate (though, as it turned out, it was the Republicans who gained seats on net). Both sides calculated there was little to be gained from compromise or restraint.

In the last part of the book, Shapiro goes over a number of possible proposals to improve the nomination and confirmation process, and deescalate the conflict over it. They range from modest changes to the confirmation process, all the way up to more radical ideas such as term limits for SCOTUS justices and various plans to "pack" or "balance" the Court. This part of the book functions as a handy guide to proposals for reform of SCOTUS, and the arguments for and against them.

While Shapiro gives a lukewarm endorsement to term limits and also urges the abolition of confirmation hearings (I disagree for reasons outlined here), on the whole he argues that such procedural and structural reforms are unlikely to defuse the conflict. At least not so long as we continue to have deep polarization over judicial philosophy and ideology. His argument on that point is highly persuasive. I would add that, in the process of considering reforms, we should be wary of those that are likely to make the conflict worse, and thereby undermine the valuable institution of judicial review - most notably court-packing.

One proposal Shapiro doesn't consider is restoring the filibuster for SCOTUS confirmations. If the filibuster is brought back and presidents must, in effect, secure 60 votes to get a nominee through, that would incentivize them to appoint more moderate justices who have at least some substantial bipartisan support. This idea deserves further exploration (perhaps in a second edition of Shapiro's book!). But it is unlikely to be implemented anytime soon, in part because the Senate majority will be reluctant to tie its own hands, especially given the prospect that the opposing party will simply change the rules back whenever they get the majority. In addition, it's not clear that more moderate SCOTUS justices are necessarily better ones. Historically, there have been many situations where "mainstream" views were badly wrong about key constitutional issues, while more "extreme" outliers were right.

Shapiro's own proposed solution to the conflict is to limit federal government power generally, and that of the executive branch in particular. In that event, he claims, the stakes of judicial review would be smaller than now, and there would be less conflict over SCOTUS nominations, as a result.

Like Shapiro, I favor tightening limits on federal power, and believe that greater decentralization can help defuse partisan conflict generally. But I am skeptical that this approach will do much to defuse conflicts over Supreme Court nominations, in particular. Many of the most contentious questions that come before the Court are actually primarily about judicial review of state and local laws. Examples include gun control, abortion, religious liberties, takings and other property rights issues, and much else. Conflicts over SCOTUS' role on these matters would continue even if federal power was cut back. Even Shapiro himself concedes that his solution is a partial one, and that it might only have a major impact in the long run.

In sum, I highly recommend Shapiro's book to anyone interested in the history of conflict over Supreme Court nominations, and in various reform proposals intended to ameliorate that conflict. If Shapiro is better at diagnosing the disease than proposing a cure, it may be because there is no easy cure available, so long as we continue to be a highly polarized society.

Show Comments (61)