The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

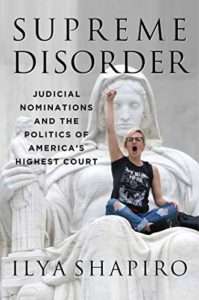

Review of Ilya Shapiro's "Supreme Disorder"

One Ilya reviews a book written by another. Hopefully, this won't exacerbate #IlyaConfusion!

In this post, I review Ilya Shapiro's important new book Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of America's Highest Court. Unfortunately, the "other" Ilya and I often get confused with each other. To prevent this review from fostering the growth of the pernicious phenomenon of #IlyaConfusion, I recommend reading my definitive guide to telling the two Ilyas apart. On to the actual review!

It's hard to think of a better-timed book than Ilya Shapiro's Supreme Disorder. The book was officially released in September, just a few days after the passing of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. That event soon led to Donald Trump's nomination of Amy Coney Barrett to fill the seat in a rushed confirmation process that concluded just before the 2020 presidential election. Democrats understandably cried foul, and pointed out how the GOP's actions contradicted their own insistence, in 2016 (when President Barack Obama nominated Merrick Garland to fill the seat vacated by the death of Justice Antonin Scalia), that Supreme Court nominations should not be taken up in an election year.

The clashes over the Garland and Barrett nominations were just part of a long series of other partisan conflicts over Supreme Court seats, including the bitterly contested nominations of Robert Bork, Clarence Thomas, Brett Kavanaugh, and others. Long gone are the days when SCOTUS nominees were routinely confirmed with little or no controversy.

Ilya Shapiro's book is not only timely, but also invaluable as a guide to the history of political battles over Supreme Court nominations, as well as a thorough discussion of possible reform proposals to improve the confirmation process. He traces the history of those conflicts from the early days of the republic on through the bitter fight over the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh in 2018.

As Shapiro shows, conflict over nominations is not a new thing. In the early 1800s, the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans each maneuvered in various ways to gain control of the courts. Later, in the 1860s, the Republican Party twice adjusted the size of the Court - each time primarily for the purpose of securing a majority of justices amenable to the party's positions on various key constitutional issues. Franklin D. Roosevelt's 1937 court-packing plan was a less successful effort to achieve a similar result (though some historians still argue that the threat of court packing triggered a "switch in time that saved nine," even as the dominant view among scholars has shifted away from that position).

At the same time, Shapiro describes how, during many periods in American history, Supreme Court nominations attracted little or no controversy. For example, John F. Kennedy's 1962 nomination of Byron White resulted in only a brief, perfunctory Senate hearing, much of which was devoted to discussion of White's earlier career as an professional football player! Such a process is almost unimaginable today.

As Shapiro explains, the key difference between 1962 and the present day is not that politicians were nicer back then or that judicial nominees were better qualified, but that in 1962 there was much less polarization on legal issues between the two major parties. Today, there is a stark difference between Republican and Democratic SCOTUS nominees on both methodology (originalism vs. living constitutionalism) and likely votes on specific issues, such as abortion, gun rights, religious liberties, executive power, campaign finance regulation, and much else. By contrast, such partisan differences between nominees were much more modest in the 1960s - and during other periods when SCOTUS nominations attracted little controversy.

In the part of his book devoted to more recent events, Shapiro traces the gradual increase in conflict over Supreme Court nominations during the last several decades. One symptom of the growing conflict is that Democrats and Republicans each have their own conflicting narratives about when the conflict began and who is responsible. Each claims that it was the other party that violated norms, while they themselves only acted defensively.

Although Shapiro is, on the whole, more sympathetic to the conservative side than the liberal one, it is to his credit that he provides as balanced an account of this history as we are likely to get. For example, many conservatives point to the defeat of Robert Bork's nomination in 1987 as a precedent-shattering event that destroyed previous norms of Senatorial deference to "qualified" nominees. Bork's defeat was indeed a notable turning point in the conflict. But, as Shapiro explains, it was prefigured by such earlier events as Republicans' successful maneuvering (with the aid of conservative Democrats), to block the elevation of Justice Abe Fortas to the position of Chief Justice in 1968-69, thereby enabling Richard Nixon to appoint the more conservative Warren Burger to the post after he narrowly won the 1968 election. Still earlier, segregationist senators had (albeit unsuccessfully) forcefully opposed the nomination of appointees seen as sympathetic to civil rights (most notably Thurgood Marshall in 1967).

Shapiro also notes that, while Bork was the victim of some ridiculous and scurrilous charges (such as bogus claims that he sought to bring back the days of segregation and slavery), he also held views on some issues that really were out of the mainstream, and are today rejected by most conservative judges and legal scholars. Among other things, he believed that the Bill of Rights was not properly "incorporated" against state and local governments, and had an extremely narrow view of freedom of speech. Viewed in historical perspective, the Bork nomination was not a sudden break with the past, but rather an escalation of a conflict that had already begun, as the parties diverged more on key legal issues in the late 1960s and 1970s.

More recent judicial nomination battles also feature gradual escalation, as opposed to completely unprovoked aggression by one side or the other. For example, the GOP's blocking of the Garland nomination in 2016 was prefigured by Democrats' very similar tactics in blocking a series of GOP lower-court nominees in the early 2000s, including some that were seen as likely future Supreme Court nominees (such as DC Circuit nominees Peter Keisler and Miguel Estrada). In all of these cases, the Democrats sat on the nomination for years, without letting it come up for a vote (much as the GOP later sat on the Garland nomination). Prominent Democrats (including then-Senator Joe Biden) also threatened to block GOP SCOTUS nominees in election years in 1992 and 2008 (though the opportunity to act on this intention did not actually arise in those years).

Blocking a Supreme Court nominee without a vote was an escalation that went beyond previous shenanigans. But it did not arise in a vacuum. The same goes for the GOP's 2017 repeal of the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees (adopted to push through the nomination of Neil Gorsuch), which built on the Democrats' earlier 2013 abolition of the filibuster for lower-court nominees (in order to push through Obama nominees opposed by GOP senators). The Democrats' actions, of course, were a response to GOP efforts to block Obama's nominees, which in turn were in part a reaction to Democrats' blocking of various George W. Bush nominees. And so it goes.

Ultimately, as Shapiro effectively explains, the roots of such skullduggery reside less in the nefarious nature of specific politicians, than in the growth of partisan polarization. The more nominees of different parties systematically diverge on key issues, the greater the incentive to block opposing-party nominees, and ram through your own - regardless of norms.

While Shapiro makes a strong effort at balance, in a few instances his relatively greater sympathy for the conservative side in these battles does lead him astray. For example, he suggests that the debate triggered by the sexual assault accusation against Brett Kavanaugh during his 2018 confirmation hearing "wasn't really about Kavanaugh," but about liberal Democrats' opposition to GOP SCOTUS nominees more generally. In reality, a plausible accusation of assault would have triggered strong opposition even during less contentious periods. The real difference is that, during an era with less polarization, a nomination with such a cloud over it would likely have simply been withdrawn. The president could take such action confident in the knowledge that the Senate would go on to confirm another nominee with a similar judicial philosophy, but no hint of scandal. And the opposition party (at least most of it) would accept the new nominee.

In 2018, the Republicans dug in on the Kavanaugh nomination in large part because they feared that withdrawing it would enable the Democrats to "run out the clock" until the 2018 midterm election after which the party might have a stronger position in the Senate (though, as it turned out, it was the Republicans who gained seats on net). Both sides calculated there was little to be gained from compromise or restraint.

In the last part of the book, Shapiro goes over a number of possible proposals to improve the nomination and confirmation process, and deescalate the conflict over it. They range from modest changes to the confirmation process, all the way up to more radical ideas such as term limits for SCOTUS justices and various plans to "pack" or "balance" the Court. This part of the book functions as a handy guide to proposals for reform of SCOTUS, and the arguments for and against them.

While Shapiro gives a lukewarm endorsement to term limits and also urges the abolition of confirmation hearings (I disagree for reasons outlined here), on the whole he argues that such procedural and structural reforms are unlikely to defuse the conflict. At least not so long as we continue to have deep polarization over judicial philosophy and ideology. His argument on that point is highly persuasive. I would add that, in the process of considering reforms, we should be wary of those that are likely to make the conflict worse, and thereby undermine the valuable institution of judicial review - most notably court-packing.

One proposal Shapiro doesn't consider is restoring the filibuster for SCOTUS confirmations. If the filibuster is brought back and presidents must, in effect, secure 60 votes to get a nominee through, that would incentivize them to appoint more moderate justices who have at least some substantial bipartisan support. This idea deserves further exploration (perhaps in a second edition of Shapiro's book!). But it is unlikely to be implemented anytime soon, in part because the Senate majority will be reluctant to tie its own hands, especially given the prospect that the opposing party will simply change the rules back whenever they get the majority. In addition, it's not clear that more moderate SCOTUS justices are necessarily better ones. Historically, there have been many situations where "mainstream" views were badly wrong about key constitutional issues, while more "extreme" outliers were right.

Shapiro's own proposed solution to the conflict is to limit federal government power generally, and that of the executive branch in particular. In that event, he claims, the stakes of judicial review would be smaller than now, and there would be less conflict over SCOTUS nominations, as a result.

Like Shapiro, I favor tightening limits on federal power, and believe that greater decentralization can help defuse partisan conflict generally. But I am skeptical that this approach will do much to defuse conflicts over Supreme Court nominations, in particular. Many of the most contentious questions that come before the Court are actually primarily about judicial review of state and local laws. Examples include gun control, abortion, religious liberties, takings and other property rights issues, and much else. Conflicts over SCOTUS' role on these matters would continue even if federal power was cut back. Even Shapiro himself concedes that his solution is a partial one, and that it might only have a major impact in the long run.

In sum, I highly recommend Shapiro's book to anyone interested in the history of conflict over Supreme Court nominations, and in various reform proposals intended to ameliorate that conflict. If Shapiro is better at diagnosing the disease than proposing a cure, it may be because there is no easy cure available, so long as we continue to be a highly polarized society.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Do you want the Supreme Court to go back to being less partisan, less controversial, and less dangerous?

It's pretty, pretty, pretty easy.

Just make sure you stop letting the Supreme Court fill in the power vacuum that Congress has abdicated. Stop SCOTUS from creating new rights, and striking down laws.

Power should be with the elected branches.

No, power should be with the people. Better to add more ways of getting rid of laws is better than removing the one useful method we have now.

But the elected branches are elected by the people and at least in theory are there to represent them, so saying that power should be with the people rather than their representatives is kind of missing the point. The people do at least get to elect members of Congress directly, and the President in a somewhat less direct manner (due to the Electoral College), whereas the Supreme Court's members are not directly elected and are answerable to no one.

Who are you, and what have you done with loki?

Oh, you don't want the SCOTUS striking down laws....

Never mind.

"Power should be with the elected branches."

That's not a completely new thought but there are a couple of problems with it. Let's say Congress passes a law to end birthright citizenship, is the court supposed to just take a pass on striking that down and leave it up to Congress?

Or let's suppose after the Supreme Court has been emasculated, and the principle established that the elected branches are supreme, that Congress and the President have a major constitutional crises with conflicting views of the President's unitary executive power and congress's power to make laws. Who is going to solve that clash with a powerless insignificant Supreme Court?

There are theoretical problems with everything we can do. For example, did you know that, as the CiC, the President can just order us to invade another country. Or that Congress can just declare war on another country for absolutely no reason?

We are running into the issue, increasingly, of politicians that are abdicating their duties. Congress and the Executive should be independently reviewing laws to determine if they are constitutional.

Numerous countries function just fine without a "Supreme Court" that functions in the same way that ours does. In effect, we have become used to the gradual accretion of power, such that elections (primarily for one party right now, but increasingly in the future for both parties) are just going to be mostly about battles over the courts. Which is terrible for political accountability, because it's so far removed from what you are voting for.

Article I Section 1 gives "all" lawmaking powers to the Congress. Judicial review is unconstitutional.

The Congress can fire both other branches. It is the most powerful branch.

In defense of the Supreme Court, the Congress has used it as its running dog to fetch controversies that are politically painful to face, like abortion. The Congress has good incentive to have the Supreme Court take heat for controversial matters. It has no incentive to obey the constitution. Maybe the Congress can be sued at the Supreme Court and forced to obey the constitution by taking back "all" its lawmaking power.

The Supreme Court lives in the Washington area. No matter how conservative, it is impossible to avoid taking on the self dealing, big government, rent seeking culture of the place. The place is not for real. Congress is still influenced by voters who live elsewhere.

Congress could help the Supreme Court by moving it to the Midwest, and by growing it to the size of a second legislature, 500 Justices, with diversity of occupational backgrounds, reflecting the general population. Put a couple of homeless addicts in there, to get their input.

Are most of the Conspirators ready to concede with respect to the election yet, or are they going to keep on clinging?

Waiting for the Kraken, guys?

Tired of winning yet, conservatives?

The election is not settled yet.

Shapiro got Josh Blackman admitted to the Supreme Court Bar. If that's not destabilizing, I don't know what is.

"such as bogus claims that [Bork] sought to bring back the days of segregation and slavery"

The claim that Bork sought to bring back segregation is hardly bogus at all. Though he claimed to "abhor" segregation, he wrote aggressively against the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 when it was before Congress, on the grounds, among others, that owners of stores ought to have the right to refuse to serve anyone they pleased. Both Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan took the same position, as do many "real" libertarians today. Goldwater also denounced Brown v. Board of Education, saying that it should not be enforced because it was incorrectly decided, essentially resurrecting the "nullification" doctrine. Justice Scalia went out of his way to demean the reasoning of the Court in Brown, making an analogy involving Adolph Hitler and the Volkswagen. Chief Justice Rehnquist repeatedly argued that "separate but equal" provision of educational services by the state was acceptable as long as they were really "equal". Reagan regarded the entire U.S. civil rights movement as a communist plot.

One way to tell you are a statist is that you cannot fathom any difference between state-mandated segregation and freedom of association.

Slavery was state-mandated. Jim Crow segregation was state-mandated. Affirmative is state-mandated discrimination.

Fuck off, slaver.

Jim Crow segregation was state-mandated.

Actually, a lot of it wasn't. And the part that was would, in many cases, have existed even with being state-mandated.

Your points are good. You need to add, the state is the lawyer profession, Government is a wholly owned subsidiary of the lawyer profession. No matter the elected figurehead, lawyers make 99% of policy decisions. This is the most toxic occupation, more toxic than organized crime. It has to be stopped.

If a baker refuses to make a cake for a homosexual wedding, I would love to open a bakery across the street, catering to homosexuals. They make more money than others, and have fewer expenses. They can go all out on wedding cakes. They are also trendy, so heterosexual couple will want my more fashionable cakes as well.

Without lawyer intentional Jim Crow laws, segregation would have died a natural death in the market.

In the darkest days of genocidal maniac, Democrat Party terror campaign against blacks, their disparities of social pathologies were small, like 10% worse off. After that act, their social disparities went to 400%, including a 4 fold higher murder rate. It took the Klan 100 years to lynch 4000 black young men. An excess of 4000 murders of them takes place each year under the Democrat Party governance, after the Civil Rights Act was passed. That Act was 100 times more lethal to black young men than the KKK.

"One Ilya reviews a book written by another. Hopefully, this won't exacerbate #IlyaConfusion!"

Are you sure that there are actually two Ilya's? Have both ever been seen in the same place at the same time?

I think they're both

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illya_Kuryakin#/media/File:David_McCallum_Man_From_UNCLE_1965.JPG

There are two.

One is a libertarian.

The other is an ardent clinger.

Let me guess. The "true libertarian" is the one droning on about open borders, right?

A third Ilya is a 19 year old Sophomore at Ohio University.

Is the third Ilya in pre-law? Ask him to take a course in Critical Thinking and another in Research Methodology. These would vaccinate him against the indoctrination of law school into supernatural doctrines, like mind reading, future forecasting, and the setting of standards of conduct by a fictitious character with the anxiety problems of Mickey Mouse.

In reality, a plausible accusation of assault would have triggered strong opposition even during less contentious periods.

But it really wasn't very plausible. No specific time/date/year or place. No contemporaneous mention of the alleged incident to anybody. There is little doubt that if that had been allowed to derail the nomination, it would be weaponized as standard procedure by finding an obscure attention-seeking partisan team-player who'd had some sort of minimal contact with a nominee sometime in the past (however distant) whose non-specific allegations could never be definitively disproved.

Such allegations would (rightly) never have been made or taken seriously during less contentious times.

There is little doubt that if that had been allowed to derail the nomination, it would be weaponized as standard procedure by finding an obscure attention-seeking partisan team-player who’d had some sort of minimal contact with a nominee sometime in the past (however distant) whose non-specific allegations could never be definitively disproved.

That's been an option for a long time. It wasn't used for Gorsuch, even though Democrats were furious about how that seat was kept vacant. Kavanaugh's problem was that, at least when he was young, he was a good example of "preppie breaking bad." There was the drinking, and there was the obvious lie about what being a "Renata alumni" really meant. I would have thought a lot more highly of him as a person had he simply admitted that he might have done some things when he was young that, in retrospect, he was sorry about.

I agree. Kavanaugh could have defused things quite a bit if he hadn't tried to portray himself as a saintly choirboy who spent his out of school hours doing service projects, and instead 1) admitted to having been what he pretty clearly was--a typical upper class high school jock of that era, and 2) spoken about how he had matured since then. But he seemed to have imbibed the Trump mindset that apologizing is a sign of weakness.

Actually Kavanaugh’s mentor is George W Bush and Bush famously never apologized for anything even lying to the country in order to invade a country.

Kavanaugh did not portray himself as a saintly choirboy. He said exactly the opposite. He said exactly what you and the previous commenter say that you wish he said: that he did things in high school that he regrets or cringes at.

Literally, the only people who ever used the term choirboy were the people attacking Kavanaugh.

Miguel and Estrada

Is that a law firm?

No. It's hendiadys.

Kavanagh's nomination was not in the face of a credible allegation of assault. It was completely non-credible, just like the claims fabricated against Justice Thomas. Shame on you for perpetuating this smear!

What is a leftist like Somin gonna do, be honest? His entire worldview falls apart on examination and contact with reality so he peddles fictional leftist narratives instead.

Among other things, [Bork] ... had an extremely narrow view of freedom of speech.

To be precise, he felt it was only political speech that was <a href=protected.

(Page 20, second paragraph from the bottom)

Constitutional protection should be accorded only to speech that is explicitly political. There is no basis for judicial intervention to protect any other form of expression, be it scientific,literary or that variety of expression we call obscene or pornographic.

This alone seems completely disqualifying.

Sorry. Link

The basic obstacle to any SCOTUS reform is the notion that the size of the court must be fixed. But there is no substantive reason why that should be the case. A system that allowed for one appointment per presidential term but no replacements due to death or resignation would be much harder to "game." But of course that would require that the number of Justices on the Court could go up or down.

As the Constitution is currently written, SCOTUS justices serve for life (technically during a time of good behavior, but in practice, that means life).

Now, you can propose to amend the Constitution. But that's the restriction now. Not that the size of the Court can't change, but that they serve for life.

I believe bratschewurst's proposal keeps lifetime appointments.

Very good, thanks.

Hopefully the issues with Bork are developed in detail in the book, because his opposition to the concept of a right of privacy and the question of whether or not the Bill of Rights applied to the states are (1) the major causes of his rejection and (2) the reason why the conservative/libertarian community should have rejected him more forecefully than they did. Bork was a test to see if principles were above politics for those of us who wanted a limited role of government in our lives, the for the most part the conservative/libertarian community failed that test, and they continue to fail it to this day.

"That event soon led to Donald Trump's nomination of Amy Coney Barrett to fill the seat in a rushed confirmation process that concluded just before the 2020 presidential election. Democrats understandably cried foul..."

It wasn't rushed, according to Pew Research Center the average Supreme Court vacancy since 1970 lasts 55 days. This vacancy lasted 48 days which seems completely reasonable compared to both the norm, and the fact that the Supreme Court term was just beginning so it was important that a few cases as possible be heard while the court was shorthanded.

As for the norms, well it used to be the norm that when a president nominated a qualified nominee then they were overwhelmingly confirmed (Scalia 98-0, RBG 96-3 ). That norm has changed (Alito 58-42 ,Goresuch 54-45).

Now the norm is if the President's party has a majority then they can get the nominee confirmed, and that has nothing to do with Trump and his nomination of Amy Coney Barrett, or even McConnell's handling of Merrick Garland.

And if anyone doubts that lets have a little thought experiment about what would have happened if Harry Reid was faced with a George Bush Supreme Court nominee in April of 2008. Anyone who says that Reid would have let that nomination go forward is smoking crack.

I'll also note that the "norm" used to be voice votes with no recorded tally. From 1900-1965 there were 28 voice votes, 13 roll call votes including 2 rejections.

Norms change.

The norm used to be if a Senator made a definitive statement they actually adhered to their committments, but today anyone who believes that is smoking crack.

"...Amy Coney Barrett to fill the seat in a rushed confirmation process..."

So you're simply dishonest. That's fine.

Don't forget the Rehnquist hearings in 1986. Senator Metzenbaum accused Rehnquist of being anti-Semitic because Rehnquist purchased a home that had a restrictive covenant on the deed prohibiting sale to Jews. This was absurd. Metzenbaum argued that Rehnquist could have used this as an excuse for refusing to sell the house to Jews. Metzenbaum made me embarrassed of my Jewish heritage.

The reason Kavanaugh wanted so badly to get on the Supreme Court is because justices get access to Renquist’s Quaalude stash...and it’s why he likes having ACB on the Court because she’s a real square.

A Judiciary Act should preclude anyone who has passed 1L from any seat on the Supreme Court. Certainly no one from the Top Tier law schools should ever be nominated. They are all bookworms who know shit about shit. Their judgement is just awful. All their decisions are based on their feelings. Their strongest feeling is a bias in favor of their employer, big, tyrannical government. These biased, know nothing lawyers get to set national policy on complicated technical subjects. They are just awful. The Congress should fast track their impeachments for their decisions.

The same Judiciary Act should move it away from the rent seeking capital of the US, a degenerate, out of control city of Washington, gayer than San Fran, where crime is encouraged. Move it to the Midwest, which the real America.

If the Supreme Court judicial review cannot be stopped, make it the size of a legislature, 500 Justices, none of which should be lawyers. The number of Justices should be even to avoid the horrifying effects of the 5-4 decisions.

What an unmitigated catastrophe this know nothing court is. These Ivy indoctrinated elitist, arrogant scumbag have no idea how incompetent they are. They are oblivious to their betrayal of the constitution. Article I Section gives "all" lawmaking power to the Congress. The Congress should bring them more awareness by impeaching them for decisions.

Or, as an alternative, you could just get some psychotherapy.

Probably electroshock

Stale remark from the KGB handbook in the trash.

"during an era with less polarization, a nomination with such a cloud over it would likely have simply been withdrawn"

During an era with less polarization, those assertions of a 'cloud' would not have gained traction, and the assertions themselves would have been laughed out of the Senate and withdrawn . ..

or would never have been made.

"during an era with less polarization, a nomination with such a cloud over it would likely have simply been withdrawn"

At first blush, I'd rather that nominations not be withdrawn due to a 'cloud' that wasn't visible, or presented, in the confirmation hearings held for appointment of the same nominee to a lower court.

And I'd like to see consequences for 'clouds' that turn out to be unsubstantiated. As in penalties for those who allege, and those who convey the allegations. Have we ever figured out why DiFi sat on what she had been given?

I support the criminalization of lawfare and of rent seeking. They should carry the penalties of perjury, and all costs should be assessed to the personal assets of the accuser, not to the taxpayer, as happens 99% of the time. The question in lawfare is, would this investigation or prosecution have taken place in absence of a political purpose?

Nitpicking should be included as a form of lawfare, and severely punished with jail time. That is the method of the Inquisition 1.0 and 2.0 in which we find ourselves. Crush the lawyer profession, the most toxic occupation in our nation. It must be crushed to save our nation.

Hi, Ilya. It is easy to distinguish the Ilyas. You are the one that totally fucked up Iraq after our invasion of it, and left it in the hands of the Shiite enemy.

You should have read the Sharia, as I have. 90% of it is pretty good, and better than our failed system, less procedural, more effective. Muslim countries have low crime rates, high rates of family formation, and much more rapid and cheaper dispute resolution. Your law school education really disabled your intellect. The latter is true of both you Ilyas.

Is ugliness a requirement to register as a Democrat? All seem to be triple baggers, two for the Democrat, and one for yourself, in case her two bags break.

Nothing worth doing is easy.

I agree. Feminism does not become a girl, no matter how beautiful the face. Of course, feminism is a lawyer masking ideology to take the assets of productive males. It does not exist outside of case. All economic and political strides made by females have resulted from male invented technology.