The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Retired Law Professor Sues Lawyer-Commenters on Law Blog

A company had a trademark canceled in a Trademark Trial & Appeal Board proceeding, based on what the Board described as the company's "delaying tactics, including the willful disregard of Board orders." The TTABlog posted about it, and some commenters criticized the company's lawyer, Ohio State Prof. Charles L. (Lee) Thomason—so he is suing them for libel.

[1.] In the Dec. 2018 SFM, LLC v. Corcamore, LLC decision, the Trademark Trial & Appeal Board had some harsh things to say about Corcamore's litigation tactics, including:

It is obvious from a review of the record that Respondent has been engaging for years in delaying tactics, including the willful disregard of Board orders, taxing Board resources and frustrating Petitioner's prosecution of this case. In view thereof, Petitioner's motion for sanctions in the form of judgment against Respondent also is granted pursuant to the Board's inherent authority to sanction.

Corcamore's lawyer in the case was Charles L. Thomason (listed in the docket as being in Columbus, Ohio), who was a clinical professor at Ohio State University Moritz College of Law until his recent retirement. The TTAB's decision is now on appeal to the Federal Circuit.

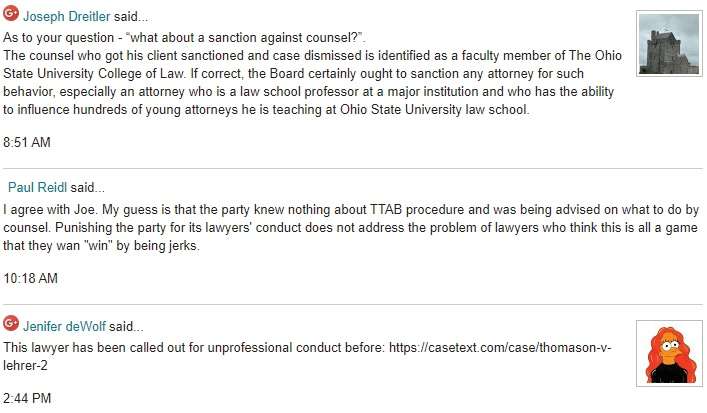

[2.] A few days later, the TTABlog, written by trademark lawyer John L. Welch, posted an item summarizing the case (though not mentioning Prof. Thomason's name), and adding (as an exhibit to the Prof. Thomason's Complaint notes), "TTABlog comment: What about a sanction against counsel?" This led to three comments, which I quote from another exhibit to the Complaint:

[3.] Last week, Prof. Thomason sued the three commenters for libel; but it seems to me that his legal theory is not sound.

[A.] The Dreitler comment began with what seems to be a correct statement of two facts—that Corcamore's lawyer was an Ohio State law professor, and that the client was sanctioned. It seems to err in saying that the "case [was] dismissed"; rather, it was the client's opposition to the cancellation proceeding that was effectively dismissed, and the other side prevailed. But that mischaracterization of the procedural situation wouldn't be damaging to Prof. Thomason's reputation; the implication of "case [was] dismissed" is that the client lost, and that is correct. (Note also that Prof. Thomason has apparently retired, and the last class I could find him teaching was in Spring 2018, so it's possible that the Dreitler comment was slightly imprecise in its tense; but any error as to that wouldn't be damaging to Prof. Thomason's reputation, either, and Thomason's Complaint more generally speaks of Thomason as a law professor, in the present tense.)

The Dreitler comment then turned to an inference that the lawyer is responsible for the result and the litigation tactics, followed by an opinion about what should happen, and what the lawyer allegedly deserves: "the Board certainly ought to sanction" the lawyer. But such opinions, however derogatory they may be, aren't actionable libel.

Now libel law recognizes that "a statement in the form of an opinion" may be actionable "if it implies the allegation of undisclosed defamatory fact as the basis for the opinion." (That's from the Restatement (Second) of Torts § 566, which the Kentucky Supreme Court has expressly adopted.) But "where the commentator states the facts on which the opinion is based, or where both parties to the communication know or assume the exclusive facts on which the comment is clearly based," there can be no liability. And that seems to be what happened here: The initial TTABlog post summarized the court opinion (in a way that Thomason's Complaint doesn't claim is defamatory); the comment accurately stated a further fact (that Thomason was a law professor) and then expressed an opinion based on those facts.

Thomason's Complaint says,

[31.] Defendant Joseph Dreitler's comments defamed plaintiff, in particular, plaintiff's professionalism, legal ability, as well as his standing as a full-time faculty member teaching at the College of Law of The Ohio State University.

[32.] Defendant Joseph Dreitler's comments stated or indicated that plaintiff was unfit for his job and duties as a law professor.

But this doesn't explain why Dreitler's comment contained any false factual allegation, as opposed to derogatory opinions. Later, the Complaint asserts (in ¶ 63) that, "each defendants' comments imply or give the impression that they have knowledge of other false and defamatory facts, on which they relied when writing the comments they published on non-party Welch's blog." But I don't see how that's so: Rather, the comments appear to just refer to the original post and the opinion cited in it, plus, in Ms. deWolf's case, the other opinion that she cites.

[B.] The Reidl comment likewise seems to be opinion: An overt "guess" that Thomason, as the lawyer, was responsible for the party's filings (an inference from the disclosed facts), followed by an inference about Thomason's mental state coupled (that he is one of those "lawyers who think this is all a game that they … 'win' by being jerks"). "[A]nyone is entitled to speculate on a person's motives from the known facts of his behavior." Haynes v. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 8 F.3d 1222, 1227 (7th Cir. 1993); see also Scholz v. Delp, 473 Mass. 242, 251, 41 N.E.3d 38, 46 (2015); Gacek v. Owens & Minor Distribution, Inc., 666 F.3d 1142, 1147-48 (8th Cir. 2012).

The Complaint asserts,

[37.] The comments defendant Paul Reidl published to non-party Welch's blog post were defamatory and directed at the plaintiff, and were defamatory per se under Kentucky law….

[38.] Defendant's comments stated or indicated that plaintiff was unfit for his job and duties as a law professor, and separately as an IP litigation attorney….

[63.] The defendants' comments include false assertions about the plaintiff "teaching at the Ohio State law school," false reference to attorney-client privileged communications about "TTAB procedure" and false assertions about the client not "being advised" but un-advised and so knowing "nothing" about such procedures, malicious comments that plaintiff is a "lawyer who thinks" adjudicative procedures are "a game," and is a "jerk," and that the plaintiff is "unprofessional" even though that word never appears in the Cancellation decision referenced in non-party Welch's blog post.

But again it doesn't explain how the comments contained false factual assertions, as opposed to pejorative characterizations and opinions.

[C.] The deWolf comment correctly points out that Thomason had "been called out for unprofessional conduct" by the Thomason v. Lehrer opinion (issued Aug. 21, 1998); that opinion begins,

In what has unfortunately become a far too frequent occurrence in this era of "scorched-earth" litigation tactics, an errant attorney has lost sight of his professional obligations to his client, his profession, and this Court.

And it continues,

The circumstances of this case, however, present the unhappy picture of a lawyer who has crossed the boundary of legitimate advocacy into personal recrimination against his adversary. Lawyers are not free, like loose cannons, to fire at will upon any target of opportunity which appears on the legal landscape. The practice of law is not and cannot be a "free fire zone." While I will impose these sanctions pursuant to the authority conferred upon me by Rule 11, I join with those who urge the legal profession to return to the standards of professionalism which have characterized the bar throughout the history of our nation.

Thomason's complaint objects (¶ 45) that "Defendant deWolf's comment omitted mentioning that a later decision of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit abrogated the Lehrer case." Indeed, the Third Circuit decision in U.S. Express Lines, Inc. v. Higgins, did reverse one of the legal conclusions in a later (Oct. 27, 1998) opinion in Thomason: The District Court in Thomason had rejected Thomason's abuse of process claim, on the grounds that alleged misconduct in a federal case should be dealt with within that case, rather than through a new lawsuit; the Third Circuit in U.S Express Lines rejected that position. But the heart of the Aug. 21, 1998 Thomason opinion pointed to by deWolf seems to me to have been unaffected by U.S. Express Lines; the court wrote in that opinion,

Thomason's section 1983 claim, specifically, the allegation that Lehrer acted under color of state or federal law by representing Absolute and Knight in asserting counterclaims against Thomason, is sanctionable under, inter alia, Rule 11(b)(2) because it is not warranted by existing law or nonfrivolous arguments for an extension or expansion of existing law….

As I have already held, Thomason's allegations that Lehrer acted under color of state or federal law in representing Absolute and Knight when Absolute and Knight named Thomason as a Defendant to their counterclaims, are wholly without merit. Even a casual investigation, let alone the reasonable inquiry required by Rule 11, see Fed.R.Civ.P. 11(b), would have revealed to Thomason that much more participation by the state and invocation of state powers and procedures is required to transform the attorney representing the client who merely alleges those claims into a state actor for the purposes of section 1983. Count I of the Second Amended Counterclaim was not "warranted by existing law or by a nonfrivolous argument for the extension, modification, or reversal of existing law or the establishment of new law."

And that "call[ing] out" of Thomason, to my knowledge, had not been reversed by the Third Circuit.

[4.] I'm also skeptical that the federal court in Kentucky has personal jurisdiction over the commenters, who seem to be in Ohio, California, and New York. The caselaw on Internet libel jurisdiction is complicated, but the most on-point Sixth Circuit case seems to cut against Thomason here. (That decision is unpublished and therefore only persuasive precedent rather than binding precedent, but it has been cited over 40 times by federal district courts in the Sixth Circuit.) In that case, the Sixth Circuit held that there was no jurisdiction in Ohio over Internet commenters who spoke about an Ohioan:

[W]hile the "content" of the publication was about an Ohio resident, it did not concern that resident's Ohio activities. Furthermore, nothing on the website specifically targets or is even directed at Ohio readers, as opposed to the residents of other states. Appellant argues that if [defendant's] goal was only to reach Massachusetts readers, then he should have used only local media, not the internet. The law does not require that people avoid using the internet altogether in order to avoid availing themselves of the laws of every state. See Revell v. Lidov, 317 F.3d 467, 473 (5th Cir.2002) (finding that Columbia University's maintenance of a website and internet message board, on which one of its professors posted an article that criticized the Texas plaintiff, was insufficient to confer personal jurisdiction in Texas over the university or the professor, because the "article written by Lidov about Revell contains no reference to Texas, nor does it refer to the Texas activities of Revell, and it was not directed at Texas readers as distinguished from readers in other states"). Additionally, although Appellant claims that [defendant]'s website links to a class action form and thereby solicits litigants, there is nothing in this form that targets Ohio, let alone mentions [plaintiff], and there is no allegation that [defendant] used this form to make repeated online contacts with Ohio residents. Consequently, because the website was not directed toward Ohio in its content or in its target audience, the case is closer to Revell and Reynolds than Calder.

Change Ohio here to Kentucky (the state in which Thomason sued), and the quote fits well: The commenters weren't speaking about Kentucky, deliberately addressing Kentucky residents, or opining about some Kentucky-specific activities on Thomason's part.

So my guess is that defendants can quickly get the case dismissed on personal jurisdiction grounds, or, if necessary, on a 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim. I'll try to keep our readers posted as to any substantive developments.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

I wish some one would start suing commenters on this lawblog.

Can I sue Sacastro and Rev. KKKirkland for being morons?

You may not. 🙂

Awww.

I do like the attention, even if meant to malign!

Not sure. Is that like defamation? Would truth be a defense?

They would have the in pari delicto defense.

Hmm...Your honor we move to dismiss because he's a moron too. Yean, I can see those 2 trying that.

Glad to see someone got that. Thought it was too obtuse.

But will he have to pay their costs in getting it dismissed? Likely not, so the chilling effect remains; The legal system will have allowed him to impose a substantial cost on them for exercising their freedom of speech.

The courts need to be a LOT less reluctant to sanction these sorts of lawsuits.

IANAL and IANAP and especially IANALP so my question is pretty naive.

A physics or chemistry or math or even a sociology professor presumably spends some time each week teaching and some time doing research which could or should lead to publication. But I gather from having read a lot over the years that sometimes professors do outside work for pay, as consultants I suppose; does that come under the guise of research which should lead to publication?

How does this apply to law professors? Several, perhaps all, Volokh Conspirators file amicus briefs from time to time, sometimes (usually?) with the help of students. Does that lead to law review articles? Is it considered consulting, or is it one aspect of how law professors do research? (Presumably research for law review articles doesn't have to include briefs.)

And how does active litigation, such as by this professor, fit into such schemes? Prof. Volokh's lawsuits over sealing court matters fits in with his research on sealing, or maybe counts towards his annual pro bono quota; I suppose the filing fees and such are written off as expenses or paid by the law school, but that's probably a minor matter.

1. To my knowledge, most law schools allow their full-time faculty to do paid consulting (whether litigation or otherwise) on the side, up to a certain number of hours per year -- at UC, it's up to 1/7 of one's time. (This standard applies to business schools, engineering schools, and the like as well, I believe.) That's seen as helping the professors see the real world, which helps improve their teaching and research; and it lets them supplement their salaries, which are generally less than what they could make in full-time practice.

2. When faculty file pro bono briefs with the help of students, that's viewed as part of the professor's teaching mission.

3. When faculty file pro bono briefs without the help of students, that's viewed as part of the professor's broader "service" work; it's not a required quota, but it's given some credit (always recalling that, at most research universities, service is viewed as less important than research and teaching, though not unimportant).

4. Sometimes such work leads directly to scholarship (that has happened to me in some such situations), and occasionally it facilitates scholarship, for instance when I move to unseal cases that are relevant to my scholarship. But that's not considered necessary, or even expected in any particular instance; working on a case (pro bono or otherwise) isn't viewed as a failure, for instance, if that particular work doesn't lead to an academic idea.

Thanks. It all sounds remarkably common sense.

From a lawyer who was called out for scorched-earth tactics one should expect further scorched-earth tactics. And, unless the Courts take a more direct and heavy hand, the profession will not return to the lost [and possibly fictitious] standards of professionalism the Court laments.

This is so true. Leopards do not change their spots.

More evidence for: "...those who can't, teach".

Here is the problem:

"Although the Board [i.e., the TTAB] does not impose monetary sanctions or award attorneys’ fees or other expenses, it has authority to enter other appropriate sanctions, up to and including judgment, against a party under Fed. R. Civ. P. 11; Trademark Rule 2.120(h), 37 C.F.R. § 2.120(h); and Fed. R. Civ. P. 37(b)(2) governing discovery; or the Board’s inherent authority."

So the TTAB really has no way to sanction an attorney; the worst it can do is sanction the party by dismissing its case, or entering judgment against it, which is what happened here.

The difficulty is actually more philosophical to the attorney-client relationship. The system works under the idea that the lawyer is the agent of the client, and general rules are the principal is responsible for its agents. In the attorney-client relationship that is simultaneously true and false. An attorney is undoubtedly the agent of the client and the client lives with the results, but those general rules are premised on the idea the principal can supervise the agent. But in law the client/principal doesn't have the requisite knowledge to do so and relies on the agent's/lawyer's counsel. That creates an issue for courts in trying to lay blame on the client and or attorney in issues like this, complicate further by the fact that whoever is at fault the other party is harmed and possibly prejudiced.

While I have no problem with the court directly sanctioning the lawyer, there is also something to be said about making the aggrieved party whole and then the client can bring suit against his attorney for malpractice where the responsible party can actually be litigated.

The sanction-and-let-the-client sue option isn't used nearly enough. Most court sanctions are tiny (and ineffective) compared to the malpractice insurance premium increase, deductible/self-insured retention, and reputational risk of a malpractice suit.

Representing himself. Fool etc.

How many people read the blog comments? Now many more will.

Streisand effect in action.

Prof. Thomason, maybe the comments were unfair to you (I have no idea), but I hope you'll consider voluntarily dismissing your case at this early stage. This will not be a good use of your time or the court's resources.

(Not a lawyer.) Is the plaintiff acting as his own attorney in this action? I suppose the info below could be out of date, but below is what the KY bar profile page (https://www.kybar.org/members/?id=32536731) shows. I presume this is the same person, as the name and address match the name and address in the linked complaint.

a. "Practice Information pursuant to SCR 3.023: I am engaged in the Private Practice of Law, and I am NOT currently covered by a policy of professional liability insurance with minimum limits of $100,000.00 per claim and $300,000.00 aggregate for all claims during the policy term."

b. A link with the text "CLE Non-Practice exemption" to a page that states:

"This member is an active member in good standing with the Kentucky Bar Association as required by the Rules of the Supreme Court of Kentucky. The member currently has a non-practice exemption wherein the member has voluntarily agreed not to practice law in Kentucky until the exemption is removed by the Continuing Legal Education Commission upon certification of completion of appropriate continuing legal education credit hours."

I don't know if he is or isn't, haven't read the complaint, but even if he is you are usually allowed to represent yourself pro se if you so choose. You don't even need to be a lawyer, let alone licensed in the jurisdiction.

I suspect the judge in the libel case might be able to do what the Trademark Trial & Appeal Board couldn’t, especially if plaintiff is a lawyer acting pro se. And it looks like this particular individual is asking for it.

A statement that a person deserves to be sanctioned might be partially a fact statement rather than a pure opinion, at least in the abstract, as it does imply the defendant did something unethical or illegal. But if so, given what the Board said about the plaintiff’s litigation strategy, it would seem that this was a fact statement that was clearly supported by evidence.

Prof. Volokh, isn't this lawyer's suit a model case for SLAPP?

Alas, Kentucky has no anti-SLAPP statute. https://anti-slapp.org/kentucky

Thanks, Andrew. Too bad.

Indeed, which is why the personal jurisdiction question might be especially important here; if Prof. Thomason had to sue the California commenter in California, for instance, the California anti-SLAPP statute might indeed apply. (There are also complicated potential choice-of-law questions here as well as the personal jurisdiction questions.)

Eugene, is it plausible that the court has personal jurisdiction over defendants, but venue is nonetheless improper? These are all individuals, so they do not "reside" in the forum. Whether "a substantial part of the events or omissions giving rise to the claim occurred" in Kentucky (28 U.S.C. §1391(b)(2)) seems like it might be a more demanding standard than the test for personal jurisdiction.

The Sixth Circuit's take on personal jurisdiction is interesting. Was not aware they had limited Calder v. Jones that way.

Q. Why did not the media defendants in the various Covington Kids defamation cases make the same argument? IIRC, the kids went to DC where the events in question took place. Then the media broadcast the (allegedly) defamatory statements nationally. So even though they are Kentucky residents, I would think that under the same rule, there is no personal jurisdiction there.