The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Public Transit Can't Ban "Disparaging" Ads

So the Ninth Circuit held, applying the reasoning from the Slants case (Matal v. Tam).

The King County (Seattle area) public transit system sold advertising space, but excluded

Advertising that contains material that demeans or disparages an individual, group of individuals or entity. For purposes of determining whether an advertisement contains such material, the County will determine whether a reasonably prudent person, knowledgeable of the County's ridership and using prevailing community standards, would believe that the advertisement contains material that ridicules or mocks, is abusive or hostile to, or debases the dignity or stature of any individual, group of individuals or entity.

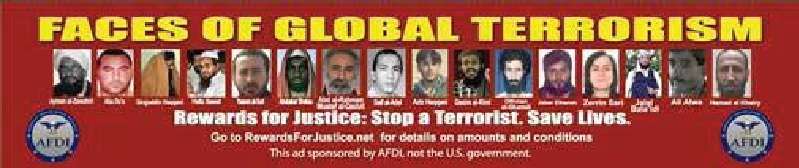

Under this policy, King County excluded the American Freedom Defense Initiative's "Faces of Global Terrorism" ad:

The King County Metro Transit General Manager explained that, in Metro's view,

[T]he "Faces of Global Terrorism" motif suggested that all persons of color who practiced the Muslim religion were, in fact, the "faces of global terrorism." Such a stereotype was demeaning and disparaging to Metro customers who have similar skin tones and religious practices, and thus, is barred under the TAP. Although a small minority of Metro Transit's ridership, persons of color who practice the Muslim religion should not be made to feel uncomfortable or singled-out when riding the bus."

But this morning the Ninth Circuit held (AFDI v. King County) that the exclusion of "demean[ing] or disparag[ing]" material was unconstitutionally viewpoint-based, and thus inconsistent with the Supreme Court's recent decision in Matal v. Tam (2017) (the Slants case). Matal struck down a federal law banning the registration of trademarks that "may disparage … persons, living or dead, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols, or bring them into contempt, or disrepute"; but in the process it held that the classification was viewpoint-based, and viewpoint-based restrictions are forbidden in government-run transit advertising sales as well:

No material textual difference distinguishes Metro's disparagement clause from the trademark provision at issue in Matal. Metro's disparagement clause, like the Lanham Act's disparagement clause, requires the rejection of an ad solely because it offends. Giving offense is a viewpoint, so Metro's disparagement clause discriminates, on its face, on the basis of viewpoint.

Metro emphasizes that the disparagement clause applies equally to all proposed ads: none may give offense, regardless of its content. But the fact that no one may express a particular viewpoint—here, giving offense—does not alter the viewpoint-discriminatory nature of the regulation [as the Matal plurality and concurrence expressly held].

It is true that this case involves a nonpublic forum, where the government generally has more leeway to restrict speech. But it is settled law that, in a nonpublic forum, regulations must be reasonable and viewpoint neutral…. Metro accepts ads on a wide range of subject matters, including terrorism, but denies access to Plaintiffs and anyone else if the proposed ad offends. We cannot conclude that the appropriate limitation on subject matter is "offensive speech" any more than we could conclude that an appropriate limitation on subject matter is "pro-life speech" or "pro-choice speech." All of those limitations exclude speech solely on the basis of viewpoint—an impermissible restriction in a nonpublic forum ….

I think this is quite right, though the line that "giving offense" is itself a "viewpoint" (a line borrowed from the Matal plurality) is a bit imprecise: The underlying point is that, when speech offends people because the views it expresses -- such as demeaning or disparaging views of certain groups -- are offensive, excluding such speech is discrimination based on viewpoint. (Some other exclusions of offensive speech, such as of offensive vulgarities, while content-based, may still be viewpoint-neutral; but that is a separate matter.)

The Ninth Circuit panel also reaffirmed (1) an earlier Ninth Circuit decision concluding that an exclusion of factually false ads from a government-owned nonpublic forum was constitutional (if applied in a viewpoint-neutrla way), and (2) yet another earlier Ninth Circuit decision concluding that ads could be excluded if there was real evidence that they caused disruption (such as violence or threats of violence). This latter decision essentially authorized a sort of "heckler's veto": The government could exclude speech because people offended by it threatened to commit crimes (there, against the government). But today's panel decision concluded that these earlier decisions didn't apply to the facts of this case.

I should note that my students Matthew Delbridge, Terran Hause, and Cheannie Kha, together with me, filed an amicus brief in this case on behalf of the Pennsylvania Center for the First Amendment, arguing that the exclusion of demeaning and disparaging speech was indeed unconstitutionally viewpoint-based, given Matal.

Show Comments (55)