The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Public Transit Can't Ban "Disparaging" Ads

So the Ninth Circuit held, applying the reasoning from the Slants case (Matal v. Tam).

The King County (Seattle area) public transit system sold advertising space, but excluded

Advertising that contains material that demeans or disparages an individual, group of individuals or entity. For purposes of determining whether an advertisement contains such material, the County will determine whether a reasonably prudent person, knowledgeable of the County's ridership and using prevailing community standards, would believe that the advertisement contains material that ridicules or mocks, is abusive or hostile to, or debases the dignity or stature of any individual, group of individuals or entity.

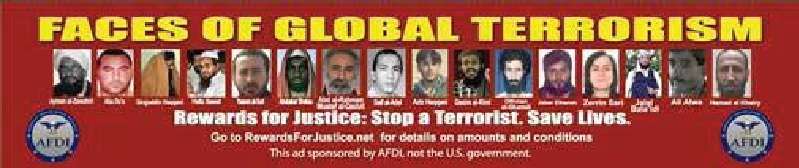

Under this policy, King County excluded the American Freedom Defense Initiative's "Faces of Global Terrorism" ad:

The King County Metro Transit General Manager explained that, in Metro's view,

[T]he "Faces of Global Terrorism" motif suggested that all persons of color who practiced the Muslim religion were, in fact, the "faces of global terrorism." Such a stereotype was demeaning and disparaging to Metro customers who have similar skin tones and religious practices, and thus, is barred under the TAP. Although a small minority of Metro Transit's ridership, persons of color who practice the Muslim religion should not be made to feel uncomfortable or singled-out when riding the bus."

But this morning the Ninth Circuit held (AFDI v. King County) that the exclusion of "demean[ing] or disparag[ing]" material was unconstitutionally viewpoint-based, and thus inconsistent with the Supreme Court's recent decision in Matal v. Tam (2017) (the Slants case). Matal struck down a federal law banning the registration of trademarks that "may disparage … persons, living or dead, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols, or bring them into contempt, or disrepute"; but in the process it held that the classification was viewpoint-based, and viewpoint-based restrictions are forbidden in government-run transit advertising sales as well:

No material textual difference distinguishes Metro's disparagement clause from the trademark provision at issue in Matal. Metro's disparagement clause, like the Lanham Act's disparagement clause, requires the rejection of an ad solely because it offends. Giving offense is a viewpoint, so Metro's disparagement clause discriminates, on its face, on the basis of viewpoint.

Metro emphasizes that the disparagement clause applies equally to all proposed ads: none may give offense, regardless of its content. But the fact that no one may express a particular viewpoint—here, giving offense—does not alter the viewpoint-discriminatory nature of the regulation [as the Matal plurality and concurrence expressly held].

It is true that this case involves a nonpublic forum, where the government generally has more leeway to restrict speech. But it is settled law that, in a nonpublic forum, regulations must be reasonable and viewpoint neutral…. Metro accepts ads on a wide range of subject matters, including terrorism, but denies access to Plaintiffs and anyone else if the proposed ad offends. We cannot conclude that the appropriate limitation on subject matter is "offensive speech" any more than we could conclude that an appropriate limitation on subject matter is "pro-life speech" or "pro-choice speech." All of those limitations exclude speech solely on the basis of viewpoint—an impermissible restriction in a nonpublic forum ….

I think this is quite right, though the line that "giving offense" is itself a "viewpoint" (a line borrowed from the Matal plurality) is a bit imprecise: The underlying point is that, when speech offends people because the views it expresses -- such as demeaning or disparaging views of certain groups -- are offensive, excluding such speech is discrimination based on viewpoint. (Some other exclusions of offensive speech, such as of offensive vulgarities, while content-based, may still be viewpoint-neutral; but that is a separate matter.)

The Ninth Circuit panel also reaffirmed (1) an earlier Ninth Circuit decision concluding that an exclusion of factually false ads from a government-owned nonpublic forum was constitutional (if applied in a viewpoint-neutrla way), and (2) yet another earlier Ninth Circuit decision concluding that ads could be excluded if there was real evidence that they caused disruption (such as violence or threats of violence). This latter decision essentially authorized a sort of "heckler's veto": The government could exclude speech because people offended by it threatened to commit crimes (there, against the government). But today's panel decision concluded that these earlier decisions didn't apply to the facts of this case.

I should note that my students Matthew Delbridge, Terran Hause, and Cheannie Kha, together with me, filed an amicus brief in this case on behalf of the Pennsylvania Center for the First Amendment, arguing that the exclusion of demeaning and disparaging speech was indeed unconstitutionally viewpoint-based, given Matal.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

===I think this is quite right, though the line that "giving offense" is itself a "viewpoint" (a line borrowed from the Matal plurality) is a bit imprecise: The underlying point is that, when speech offends people because the views it expresses -- such as demeaning or disparaging views of certain groups -- are offensive, excluding such speech is discrimination based on viewpoint.===

The purpose of speech is to have an effect on others to, ultimately, change their behaviors. Eventually the rubber must meet the road, as having only the right to talk abstractly is just a book club. Making people feel bad, or offended, (as opposed to outright threats) is thus a perfectly legitimate tool in the golf bag of speech effects.

Big Hulking Government: Don't make me censorious. You won't like me when I'm censorious.

"Making people feel bad, or offended, (as opposed to outright threats) is thus a perfectly legitimate tool in the golf bag of speech effects."

But it's still a dirty trick if you won't be there when and where the offended are so effected, and somebody else will.

If you want to tell a room full of (insert group) that they are (reason to be offended), then you will feel the effects of your choice to be inflammatory, and this provides some motivation for self-regulation. But if you will be somewhere else, while (third-party) is there to take the brunt of your speech's effects, I can understand why (third-party) doesn't want to be a participant in your speechifying.

The bus drivers and customer-service agents don't want to deal with some jackass's choice to be deliberately offensive in the signs they put on the buses and bus stops.

I wonder if there would be a Constitutional complaint if the name, address, and other contact information were superimposed over the signs, without the knowledge or permission of the persons buying the ads.

There would be as the First includes the right to speak anonymously. And wanting to force names attached to speech so there can be reprisals is why it's a value to not allow it.

People want to abandon that value because it gets in the way of them using it against others when they should pay attention to historical abuses of deanonymizing speech (long before the Internet) that...they might not be so keen on.

"People want to abandon that value because it gets in the way of them using it against others [...]"

The deanonymizing of bus ads can probably be accomplished without breaking the Republic, despite your dire warning otherwise. I don't fear this, because I neither place nor consume ads on buses in Seattle.

Oh, well, you probably should have filed an amicus brief to alert the court that you neither place nor consume bus ads in Seattle, so they could consider this important information.

Yes, that makes sense. But, I didn't want to pay the filing fee, so I let the court wing it without my input.

===The deanonymizing of bus ads ***so social ostracism and firing can be used to silence opinions the government doesn't like*** can probably be accomplished without breaking the Republic===

Ftfy and I beg to differ.

"Ftfy"

Please don't try to speak for me. You're not good at it.

Yeah, you also don't understand what that phrase means.

Sorry, I didn't know you were disabled.

So, no disparaging words...but I bet the skies are still cloudy all day.

Actually laughed out loud.

It stands to reason that transit authorities have a compelling interest in keeping their ridership from feeling uncomfortable or unsafe from ads that cross a certain line -- e.g., if AFDI were to put up large, bold "MUSLIMS GO HOME" advertisements across the subway, I would imagine the Muslim population would be fairly disincentivized to use public transit. I think a lot of people, non-Muslims included, would be unnerved by seeing that kind of an ad.

I would agree that censoring any potentially "offensive" ad is problematic, as the 9th Circuit found here, but other transit authorities like D.C. Metro have tried to get in front of the issue (inspired by the same plantiffs in this case, AFDI) by prohibiting ads that were both for and against *any* kind of issue, so as to have a content-neutral policy. But even that policy was roundly mocked and the ACLU sued D.C. Metro to upend the policy.

So, what is a transit provider to do?

How about be a transit provider and not a pitch platform to a possibly captive audience.

Selling ad space subsidizes fares, and people riding the bus probably appreciate this in the abstract.

Sure, selling ads on transit help defray expenses, but so would selling ads on other government vehicles and facilities. The public interest in the government defraying its expenses by selling advertising on the wall of City Hall, or running monitors displaying video advertising to people waiting in line for permits, doesn't exempt the sale of such ad space from the requirements of the Constitution, either.

Waiting for the first Nasa rocket with an ad on it, vertical past a tower camera as it climbs into the sky, "Like my giant rocket? Toxic masculinity 4ever!"

"Waiting for the first Nasa rocket with an ad on it"

You're about sixty years late, then. There have been ads on NASA rockets since the beginning. They've all had images and text identifying their biggest sponsor.

" The public interest in the government defraying its expenses by selling advertising on the wall of City Hall"

Not an apt comparison, since City Hall serves the entirety of the population, whereas buses serve a primarily low-income sector.

Much the way the law against sleeping under bridges keeps both rich men and poor men from sleeping under bridges, fare costs for public transit are not distributed evenly across all citizens.

Money is fungible. Revenue from ads displayed on the side of City Hall could be earmarked to lower transit fares. Such an earmarking of funds, rather than use for other ends, would not plausibly change the Constitutional rules about the municipality selling that display space.

"Such an earmarking of funds, rather than use for other ends, would not plausibly change the Constitutional rules about the municipality selling that display space."

True enough. What, if anything, is it relevant to?

The government isn't acting as a transit provider in these cases, it's acting as a seller of advertising space. It is perfectly possible for it to keep acting as a transit provider without selling advertising space.

" It is perfectly possible for it to keep acting as a transit provider without selling advertising space."

It's also possible for it to stop acting as a transit provider.

That, too. For example, it could sell off the transit system assets and, if it still wanted one, hire a contractor to provide one. The contractor then could, as a private entity, sell its own ad space if it liked, with whatever rules it thought would serve it best.

Sure. They could also make all the zoo animals they're already housing work as bus drivers to cut costs. Win-win!

I think gov't as business partner should be held to a much lower standard.

The license plate case, and this case; if the gov't wants to dissociate itself from people it should have that option like any consumer or vendor.

But the (monolithic, coercive) government is not just "any consumer or vendor".

It takes a pretty expansive view to get "monolithic" or "coercive" as a valid descriptor of government's role in advertising.

Now, if the city tries to pass a law prohibiting controversial ads anywhere in the city, you have something to talk about. Is that what this is? I don't think that's what this is.

Those adjectives modified "government".

Reading is hard.

"Reading is hard."

Not everybody suffers your disability.

"Those adjectives modified "government"."

Particularly poorly, in this case, because (as was pointed out) neither one applies in this case.

Re: the "heckler's veto"

If the transportation system refused - just as an example - right-wing advertisement because of threats of violence by the left, but not left-wing advertisement despite threats of violence by the right, would this be valid, or is the "heckler's veto" also constrained by viewpoint discrimination?

The government must enforce the disruption rule (like the false statements rule) without viewpoint discrimination of its own -- in your example, the discriminatory enforcement of the rule would be unconstitutional.

Thank you. That would mean that acceding to a heckler's veto from one side would require acceding to one from the other side [even if it were simply tit-for-tat], which would ultimately force the government to refuse any viewpoint-oriented advertisement at all.

Of course, they could always argue that they take threats of violence from - just for example - the left more seriously than those from the right. Oh what a lovely argument that would make in court.

I would hope a court could discern the reason the government silenced both sides was because it wanted to silence one side only, but could not get away with it.

And therefore it may not silence either side in that instant case. Punching both sides because you unconstitutionally want to punch one does not get rid of the constitutional infirmity, especially with something like the Firat Amendment.

"And therefore it may not silence either side in that instant case."

Well, actually, it can silence both sides, by simply declining to accept ads of any type, and using the space only to advance its own message(s). Buy Washington Lottery tickets, don't drink and drive, visit the local zoo.

At least two of your three examples are provocative and viewpoint based.

Buy lottery tickets encourages gambling, which actually carries religious import.

Visit the local zoo - ask PETA what they would say about that.

"At least two of your three examples are provocative and viewpoint based."

And?

The point remains that, as owner of the buses, Metro can put its own messages in the overhead signage space. They don't have to make that space available to anyone else.

Snowflakes gonna flake and this is the correct outcome.

Anyone want to go in with me on a "YAAAY Atheism!" campaign in the Tupelo, Mississippi bus system?

I just checked, apedad, and Tupelo /does/ have a transit system, with three routes (blue, green, and yellow). But they have a photo of a bus, and it doesn't appear to have any ads. Apparently they heard you coming.

Not "YAAAY Atheism!" It should be "God is a lie. A comforting lie, to some people, but a lie. If your parents or teachers are telling you that fairy tales are true, they are lying to you. Don't ask them why. Just know they are lying -- because if you are older than 12 or so, you are old enough to know that fairy tales are not true."

Children who use public transportation to get to school deserve to have the information needed to enable them to handle childhood indoctrination.

That message, especially in backward states, should be enough to get the public to think about the issue of restrictions on transit system advertisements. A public service in at least two ways.

What finally got them to reconsider public funding of religious schools was when the Muslim schools started showing up in the funding line.

I'm not 100% confident that offensive issue-oriented bus ads will have a lot of positive effect, but if they're willing to put their money where their mouth is, and other ads are allowed, then - offensive or not - let them try.

I seem to recall a case in the 1950s challenging the existence of ads on public property. The plaintiffs lost only because a couple of Justices recused themselves, saying they found these ads so personally offensive they didn't believe they could decide the matter impartially.

Today, recusal on these grounds would be highly unlikely - indeed, Justices tend to assume offense comes from constitutional rather than personal sources.

The argument was basically that these ads take people's property - their attention and privacy - for the benefit of a private party, and hence without any public purpose, constituting a taking and a deprivation of liberty and property without due process of law.

Perhaps the issue should be revisited if Kelo is.

That line of reasoning would kill the broadcasting industry, and might deal a mortal wound to cellular telecommunications.

The case was Public Utilities Commission v. Pollak, 343 US 451 (1952). It involved ads blaring from loudspeakers. Justice Frankfurter wrote the recusal opinion.

Shorter FF: "There's no way I can be impartial about all that horrible noise I have to put up with on the bus, I recuse myself!"

Nowadays the Justices drive cars. Especially Fiats.

Get government out of the bus business. Problem solved,no expensive litigation.

Your working theory is that people driving in cars and looking at the ads in the buses?

I don't want public money going to religious schools, regardless of which fairy tales they choose to promote. It was the "other guys" who wanted to use public money for religious schools, until they found out that other religions would ALSO stick their hands into the public's pockets.